Basking Shark

Cetorhinus maximus

This slow-moving migratory shark is the second largest fish, growing as long as 40 feet and weighing over 5 tons. It is often sighted swimming close to the surface, huge mouth open, filtering 2,000 tons of seawater per hour over its complicated gills to scoop up zooplankton. Basking sharks are passive and no danger to humans in general, but they are large animals and their skin is extremely rough, so caution is urged during any encounters.

Order – Lamniformes

Family – Cetorhinidae

Genus – Cetorhinus

Species – maximus

Common Names

English language common names include basking shark, bone shark, elephant shark, hoe-mother, shark, and sun-fish. Other names are albafar (Portuguese), an liamhán gréine (Irish), beinhákarl (Icelandic), brugd (Swedish), brugda (Faroese), brugde (Danish), büyük camgöz (Turkish), büyükcamgöz baligi (Turkish), cação-peregrino-argentino (Portuguese), colayo (Spanish), dlugoszpar a. rekin gigantyczny (Polish), éléphant de mer (French), frade (Portuguese), gabdoll (Maltese), gobdoll (Maltese), jättiläishai (Finnish), kalb (Arabic), karish anak (Hebrew), koesterhaai (Afrikaans), k’wet’thenéchte (Salish), mandelhai (German), marrajo ballenato (Spanish), marrajo gigante (Spanish), peixe frade (Portuguese), peixe-carago (Portuguese), peixe-frade (Portuguese), peje vaca (Spanish), pèlerin (French), peregrino (Spanish), peshkagen shtegtar (Albanian), pez elefante (Spanish), pixxitonnu (Maltese), poisson à voiles (French), relengueiro (Portuguese), requin (French), requin pèlerin (French), reremai (Maori, reuzenhaai (Dutch), riesenhai (German), sapounas (Greek), squale géant (French), squale pèlerin (French), squalo elefante (Italian), tiburón canasta (Spanish), tiburón peregrino (Spanish), tubarão frade (Portuguese), and ubazame (Japanese).

Importance to Humans

In the past, basking sharks were hunted worldwide for their oil, meat, fins, and vitamin rich livers. Today, most fishing has ceased except in China and Japan. The fins are sold as the base ingredient for shark fin soup. A “wet” or fresh pair of fins can fetch up to $1,000 in Asian fish markets while dried-processed fins generally sell for $350 per pound. The liver is sold in Japan as an aphrodisiac, a health food, and its oil as a lubricant for cosmetics. From a 4-ton (3629 kg), 27 feet (8.2 m) basking shark, a fisherman will get 1 ton of meat and 100 gallons (380 liters) of oil.

Interestingly, many tales of sea serpents and monsters have originated from sightings of basking sharks cruising single file, snout to tail, near the surface of the water. In addition, the decomposing remains of basking shark carcasses have been brought to the surface by commercial fishing gear and have also been known to wash up on shore. Due to the basking shark’s relatively small skull in comparison to its body length, it seems unbelievable to many people that these carcasses are those of a shark rather than some unknown beast.

More recently, the basking shark has sparked an interest in eco-tourism operations.

Danger to Humans

Basking sharks are not considered dangerous to the passive observer and are generally tolerant of divers and boats. Despite this, its sheer size and power must be respected (there are reports of sharks attacking boats after being harpooned). In addition, contact with its skin should be avoided, as its large dermal denticles have been known to inflict damage on divers and scientists.

Conservation

As with other sharks, basking sharks are vulnerable to overfishing for several reasons. They have a lengthy maturation time, slow growth rate and a long gestation period. These factors combined with an already depleted population in many areas have prompted many countries to establish laws to protect the basking shark from further exploitation. The following is a list of significant conservation developments over the past ten years.

- 1993 – It was reported that the global population of basking sharks had dropped by 80% since the 1950’s.

- 1995 – A Barcelona Convention Protocol added the basking shark to its list of Threatened Species.

- 1997 – The U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service banned the fishing for basking sharks in US Federal Atlantic waters.

- April 1998 – The British Government announced a movement to protect the basking shark in UK waters, under Appendix II of CITES (The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of flora and fauna). This request would not have banned the hunting of basking sharks worldwide, but would have demanded that countries that engaged in trading basking shark parts keep detailed records. These records could then be used to determine whether the fishery was sustainable or not.

- October 2000 – U.S. Departments of Commerce and Interior announced their support for UK movement to protect basking sharks.

- November 2000 – AFS (American Fisheries Society) lists the population of basking sharks in the western Atlantic as conservation dependent (reduced but stabilized or recovering under a continuing conservation plan) and vulnerable in the eastern Pacific.

- Presently – The FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations) is leading a plan to establish international shark fishery management strategies for a number of species, including the basking shark.

The basking shark is also currently categorized as “Vulnerable” throughout its range and “Endangered” in the northeast Atlantic Ocean and north Pacific Ocean regions by the World Conservation Union (IUCN). The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

> Check the status of the basking shark at the IUCN website.

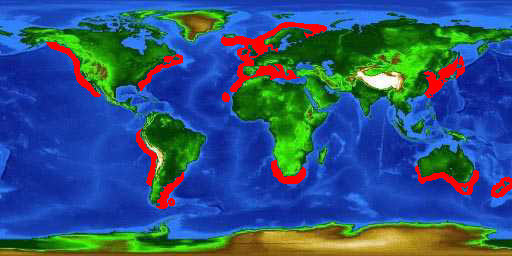

Geographical Distribution

The basking shark is a coastal-pelagic species found throughout the world’s arctic and temperate waters. In the western Atlantic, it ranges from Newfoundland to Florida and southern Brazil to Argentina and from Iceland and Norway to Senegal, including the parts of the Mediterranean in the eastern Atlantic. It is found off Japan, China and the Koreas as well as western and southern Australia and the coastlines of New Zealand in the western Pacific and from the Gulf of Alaska to the Gulf of California and from Ecuador to Chile in the eastern Pacific.

Habitat

The basking shark is typically seen swimming slowly at the surface, mouth agape in open water near shore. This species is known to enter bays and estuaries as well as venturing offshore. Basking sharks are often seen traveling in pairs and in larger schools of up to a 100 or more. Its common name comes from its habit of ‘sunning’ itself at the surface, back awash with its first dorsal fin fully exposed.

Basking sharks are highly migratory. Off the Atlantic coast of North America it appears in the southern part of its range in the spring (North Carolina to New York), shifts northward in the summer (New England and Canada), and disappears in autumn and winter. Off the southwest coast of the United Kingdom in the northeast Atlantic, the basking shark feeds at the surface of coastal waters during the summer. These sharks are absent from November to March, suggesting a migration beyond the continental shelf during the winter months. This is explained by the high zooplankton density (the primary food of the basking shark) that exists in these waters during late spring and early summer. Sightings of groups of individuals of the same size and sex suggest that there is pronounced sexual and population segregation in migrating basking sharks.

Distinguishing Characteristics

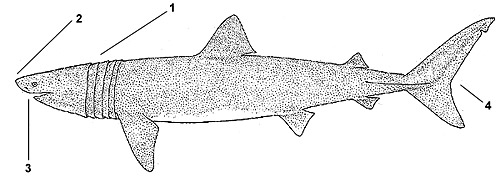

1. Head is nearly encircled with large gill slits

2. Snout is bulbous and conical

3. Mouth is large and subterminal with small hooked teeth

4. Caudal fin lunate with a single keel on the caudal peduncle

Biology

Distinctive Features

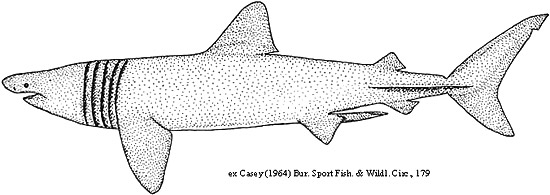

The basking shark is one of the most recognizable of all sharks. Its massiveness, extended gill slits that nearly encircle the head and lunate caudal fin together help distinguish it from all other species. It possesses a conical snout and numerous large gill rakers modified for filter feeding. Its enormous mouth extends past the small eyes and contains many small, hooked teeth. The basking shark has a very large liver that accounts for up to 25% of its body weight. The liver is high in squalene, a low-density hydrocarbon that helps give the shark near-neutral buoyancy.

Coloration

Dorsal surface is typically grayish-brown but can range from dark gray to almost black. Ventral surface may be of the same color, slightly paler or nearly white.

![(A) Labial, (B) basal and (C) lateral views of basking shark teeth. Images courtesy Compagno (1990) NOAA Tech. Rep. NMFS 90], (D) Enlarged photo of a portion of jaw. Image courtesy Radcliffe (1916) Bull. Bur. Fish. Circ. 822](https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/66/2017/05/Cetorhinus-maximus-05.jpg)

Dentition

The basking shark possesses hundreds of tiny teeth. Those in the center of the jaws are low and triangular while those on the sides are more conical and slightly recurved. There is typically a wide space on the center of the upper jaw with only scattered teeth.

Size, Age, and Growth

Second only to the whale shark (Rhincodon typus) in size, the basking shark can reach lengths up to 40 feet (12 m). The average adult length is 22-29 feet (6.7-8.8 m). Size at birth is believed to be between 5-6 feet (1.5-1.8 m). The basking shark is an extremely slow-growing species and may grow to 16-20 feet (5-6 m) before becoming mature.

Food Habits

Along with the whale shark and the megamouth shark (Megachasma pelagios), the basking shark is one of three species of large, filter-feeding sharks. However, the basking shark is the only one that relies solely on the passive flow of water through its pharynx by swimming. The basking shark is usually seen swimming with its mouth wide open, taking in a continuous flow of water. The whale shark and megamouth shark assist the process by suction or actively pumping water into their pharynxes. Food is strained from the water by gill rakers located in the gill slits. The basking shark’s gill rakers can strain up to 2000 tons of water per hour. These sharks feed along areas that contain high densities of large zooplankton (i.e., small crustaceans, invertebrate larvae, and fish eggs and larvae). There is a theory that the basking shark feeds on the surface when plankton is abundant, then sheds its gill rakers and hibernates in deeper water during winter. Alternatively, it has been suggested that the basking shark turns to benthic (near bottom) feeding when it loses its gill rakers. It is not known how often it sheds these gill rakers or how rapidly they are replaced.

Reproduction

Limited information is available on the reproduction of the basking shark. Only one female carrying an embryo has ever been recorded. This shark was said to have given birth to five live young and one stillborn all ranging from 1.5-2 m (4.5-6 ft) in length. The widely accepted theory is that the basking shark is ovoviviparous. The gestation period is 3 years or longer. It is also been proposed that they use a method of embryonic nutrition known as oviphagy, in which an embryo feeds on unfertilized eggs or other embryos within the uterus. It has been estimated that females reach sexual maturity between 12-16 years.

A characteristic feature of the juvenile basking shark is the long, hook-like snout. It is thought that this snout is useful in feeding in the womb and early feeding after birth by increasing water flow through the mouth. The mouth changes its shape and relative length rapidly during the first year after birth.

Predators

Basking sharks have few if any predators, however white sharks have been reported to scavenge on the remains of these sharks.

Parasites

Many people have witnessed individual sharks leaping from the water. This phenomenon is not fully understood but some believe the shark may be trying to rid itself of parasites or commensals such as remoras and especially sea lampreys (Petramyzon marinus), which are often seen attached to the skin of the basking shark. The lamprey cannot cut through the denticle-armored skin, but they may be enough of an irritant to cause a reaction like jumping or rubbing against an object or the bottom to dislodge them. The cookiecutter shark (Isistius brasiliensis) has also been known to attack basking sharks by using its suction cup-like lips and muscular pharynx to bore out plugs of flesh on the outside of the shark.

Taxonomy

Occasionally known as “sunfish” or “sailfish” in certain areas of the world, the basking shark is the only member of the family Cetorhinidae. It was first described by Gunnerus in 1765 from a specimen from Norway and was originally assigned the name Squalus maximus. Synonymous names include Squalus isodus Macri 1819, Squalus elephasLesueur 1822, Squalus rashleighanus Couch 1838, Sqalus cetaceus Gronow 1854, Cetorhinus blainvillei Capello 1869,Selachus pennantii Cornish 1885, Cetorhinus maximus infanuncula Deinse & Adriani 1953 and Cetorhinus maximus normani Siccardi 1961). The currently accepted scientific name is Cetorhinus maximus as assigned by Gunnerus in 1765. The genus name Cetorhinus is derived from the Greek, “ketos” = a marine monster, whale and “rhinos” = nose while the species name maximus is Latin, meaning “great.”

Occasionally known as “sunfish” or “sailfish” in certain areas of the world, the basking shark is the only member of the family Cetorhinidae. It was first described by Gunnerus in 1765 from a specimen from Norway and was originally assigned the name Squalus maximus. Synonymous names include Squalus isodus Macri 1819, Squalus elephasLesueur 1822, Squalus rashleighanus Couch 1838, Sqalus cetaceus Gronow 1854, Cetorhinus blainvillei Capello 1869,Selachus pennantii Cornish 1885, Cetorhinus maximus infanuncula Deinse & Adriani 1953 and Cetorhinus maximus normani Siccardi 1961). The currently accepted scientific name is Cetorhinus maximus as assigned by Gunnerus in 1765. The genus name Cetorhinus is derived from the Greek, “ketos” = a marine monster, whale and “rhinos” = nose while the species name maximus is Latin, meaning “great.”

Prepared by: C. Knickle, L. Billingsley & K. DiVittorio

Portions of this text are used with permission from the FAO Sharks of the World Species Catalouge.