By: George H. Burgess

Florida Program for Shark Research Director Emeritus

There are limited openings for biological scientists and the pay is not great. My standard advice to those considering the field is this: you should consider biology as a career ONLY if you truly have passion for it. If you do, and you work hard, a job will likely be available when the time comes. Folks that look to biology as only a job ultimately are less likely to find jobs because others with fire in their souls for the subject inevitably will have walked the extra mile to be better prepared for the job opening. Competition is indeed intense for biologist positions and a basic Darwinian principle, survival of the fittest, certainly applies in the biological employment line.

There are limited openings for biological scientists and the pay is not great. My standard advice to those considering the field is this: you should consider biology as a career ONLY if you truly have passion for it. If you do, and you work hard, a job will likely be available when the time comes. Folks that look to biology as only a job ultimately are less likely to find jobs because others with fire in their souls for the subject inevitably will have walked the extra mile to be better prepared for the job opening. Competition is indeed intense for biologist positions and a basic Darwinian principle, survival of the fittest, certainly applies in the biological employment line.

In high school take as many science courses as you can and also emphasize math and reading/writing classes. The latter is especially important since reading and writing skills seem to be somewhat lacking in many incoming undergraduate students these days. A good biologist needs to be able to readily read and comprehend what others have found and clearly convey scientific results to the scientific community. Also plan to take a foreign language: English, Spanish, and French are probably the most often utilized in biological literature. Start learning basic computer programs because computers are the pencils/pens of today’s universities.

Major in biology, zoology, botany, or microbiology at a four-year institution of higher learning. Your choice of university depends on personal financial and social needs. Choose a school that emphasizes one of those majors by offering a variety of undergraduate and graduate courses. Avoid schools that clearly emphasize other curricula at the expense of your chosen field.If you want to be a professional biologist, you probably should plan to continue your schooling through graduate school. With some exceptions, a master’s or doctorate degree are just about mandatory these days to get a decent biologist job. Your undergraduate time will be spent preparing you for that next step. Specialization within the field usually occurs at the graduate level, but if you have your mind set on one particular biological interest (such as ichthyology, physiology, molecular evolutionary studies, etc.) as an undergraduate you can take courses in that area and (see below) try to volunteer or work in the laboratory of someone engaged in that line of research.

Major in biology, zoology, botany, or microbiology at a four-year institution of higher learning. Your choice of university depends on personal financial and social needs. Choose a school that emphasizes one of those majors by offering a variety of undergraduate and graduate courses. Avoid schools that clearly emphasize other curricula at the expense of your chosen field.If you want to be a professional biologist, you probably should plan to continue your schooling through graduate school. With some exceptions, a master’s or doctorate degree are just about mandatory these days to get a decent biologist job. Your undergraduate time will be spent preparing you for that next step. Specialization within the field usually occurs at the graduate level, but if you have your mind set on one particular biological interest (such as ichthyology, physiology, molecular evolutionary studies, etc.) as an undergraduate you can take courses in that area and (see below) try to volunteer or work in the laboratory of someone engaged in that line of research.

What you need to do to become a professional biologist:

- Major in biology, zoology, botany, or microbiology at a four-year institution of higher learning. Your choice of university depends on personal financial and social needs. Choose a school that emphasizes one of those majors by offering a variety of undergraduate and graduate courses. Avoid schools that clearly emphasize other curricula at the expense of your chosen field.

- Study a lot and work hard to get good grades.

- Take key background classes in chemistry (through organic), math (through calculus), physics, statistics (yeah, it’s dull, but you’ll really use this stuff), and computer utilization (or spend time learning major programs, especially databases).

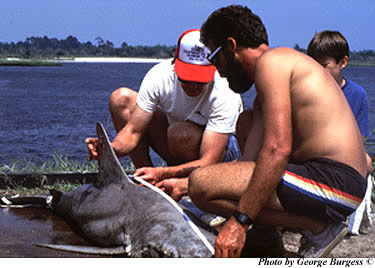

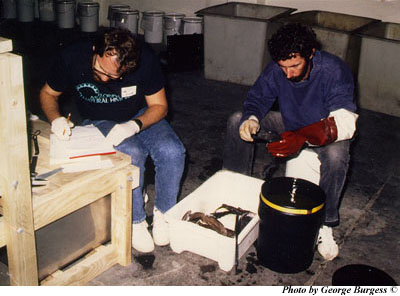

- At your university, try to hook up with a professor and/or a graduate student by volunteering to work in their lab or in the field with them. Ask them lots of questions and learn to listen. Take advantage of meeting their friends and colleagues when the chance occurs – and ask them questions, too. If you demonstrate aptitude and desire, letters of recommendation for graduate school may be forthcoming down the line. Don’t ignore the possibility of volunteering or working during summer months when there is less competition from similar-minded undergraduate students at many universities.

- Study a lot and work hard to get good grades.

- Start thinking about taking the GRE’s (general and biology) in your junior year. Grab a couple GRE study guides and put some time studying in the areas you feel weakest. Take the GRE 2-3 times to get the highest score you can.

Keep thinking about how great it will be when you won’t have to study physics, calculus and other subjects that may bore you. Allow occasional dreams about being in the field with the critters or plants you love. Love of that biota and environment is the passion which sustains biologists, not chances for employment or advancement (often poor) or salaries (even poorer).

Keep thinking about how great it will be when you won’t have to study physics, calculus and other subjects that may bore you. Allow occasional dreams about being in the field with the critters or plants you love. Love of that biota and environment is the passion which sustains biologists, not chances for employment or advancement (often poor) or salaries (even poorer).- Study a lot and work hard to get good grades.

- Start looking at potential graduate schools during your junior year. Graduate programs should match your area of interest – if you want to study fisheries it is a waste of time to go to a school with a great academic reputation but no expertise in fisheries; if you are interested in molecular biology, don’t go to a “whole animal” department, etc.

- Identify potential major professors from the list of graduate faculty at institutions you have short-listed by reading about their areas of research interest and tracking down and reading their recent publications. Start sending out “feeler” letters to potential major professors late in your junior year to initiate communication, determining whether they are interested in you as a student, what the chances are for financial assistance, the number of graduate students they have, etc.

- If possible, in the summer before your senior year or in the fall make site visits to your final choice sites to see the facilities, talk to your potential major professor and graduate student coordinator, and (VERY IMPORTANT) talk in confidence to graduate students of the department to get the skinny on the department and the professors. The latter saves many a poor matching of student-professor before it begins.

- Apply about midway through your senior year to your short list of institutions. By this time you should be able to pontificate on the admission form about your great grades, undying love for critters, and (IMPORTANT) focus of graduate research. The latter doesn’t have to be too specific (although it can be if you’ve already established a working relationship with a potential major professor), but admission committees members frown on “I want to be a marine biologist and feed the world,” “I want to swim with the dolphins, they’re so cuddly,” and similar responses. More effective is “I want to study respiratory physiology, but I’m not sure on what taxon” or, “I want to study reef community ecology, preferably the Neotropics.” If you have cemented a relationship with a major professor, it’s ok to brag a bit: “I have spoken with Dr. Smutz and he has agreed to take me on if his grant comes through.”

- Don’t aim too high in your all your grad school choices – make sure there’s at least one or two “gimme’s” that you can count on in case the pie-in-the-sky choices go down in flames. This is a time for personal honesty – even if you really are the greatest potential grad student out there, a 2.5 GPA ain’t gonna get you into the Fortune 500 grad programs. Be realistic in your choices and evaluating your chances of acceptance. You may have to apply (and hopefully be accepted at) a lesser school for your master’s in order to demonstrate your skills, then move on to a more prestigious school for your Ph.D. If your grades are lacking, point out things that demonstrate your burning desire to be a biologist, such as independent studies, volunteering or employment in a laboratory, field courses/activities, etc. If non-biology courses pulled down your GPA, point to your higher biology or science GPA. If you had trouble the first couple of years in school, say so and point to your junior/senior GPA to demonstrate improvement. Show the admissions committee why you are a good risk.

- If you don’t succeed in getting into graduate school the first time around or realize your grades simply are too poor for a realistic chance at acceptance, consider taking a year or two off before reapplying. In the interim, don’t pout and feel sorry for yourself. Instead, settle close to an institution with a good biology program and try to stay close to the action by volunteering or working for a professor. Take some post-baccalaureate courses and work hard in them. Network with as many professors and graduate students as possible. Better grades in these courses and demonstrated interest may help you into school through the direct intervention of a potential major professor who sees your spirit and desire. Oh, by the way, study like mad and work hard to get good grades.