Pristis zijsron

Sawfish look a lot like sharks, but they are actually rays. Their unusual snout, or rostrum, is studded with “teeth” (specialized scales) and is used to stun schooling fish by swinging side to side. The green sawfish is the largest species of sawfish, growing to 24 feet in length. The rostrum alone can be over 5 feet long.

Order – Rhinopristiformes

Family – Pristidae

Genus – Pristis

Species – zijsron

Common Names

Afrikaans: langkam-saagvis

Arabic: abusef, sayyaf, and sayyafah

Australia Aboriginal: dindagubba (Last and Stevens, 1994)

Dutch: groene zaagrog

Danish: grøn savrokke

English: green sawfish, longcomb sawfish, longsnout sawfish, narrowsnout sawfish, narrow-snouted sawfish, sawfish (Last and Stevens, 1994)

French: poisson-scie

Guugu Yimidhirr: yubadhi

Portuguese: tubarão-serra africano

Tamil: vella-sorrah and vezha

Importance to Humans

Green sawfish in Australia are occasionally caught in prawn trawlers and inshore gill nets targeting barramundi (Lates calcarifer) and threadfins (Polynemidae) (Field et al., 2008), though they are occasionally targeted purposefully for food. All sawfishes’ fins are more valuable than their meat on the Asian ‘shark fin’ market. The eggs, liver oil, rostra, and bile of sawfishes are used in Chinese traditional medicine. Their rostra are sold as curios (Guilford, 2014). Sawfish are significant in Australian Aboriginal culture, often depicted in bark paintings. They are occasionally caught in fishing tournaments, but rarely targeted by sport anglers. Large green sawfish are capable of long fights on heavy tackle. The International Game Fish Association does not have a record holder for the green sawfish.

Danger to Humans

All sawfishes are harmless if left undisturbed. Humans are too large for potential prey. Though care must be taken when handling or approaching a sawfish, as they may defend themselves using their powerful rostrum.

Conservation

IUCN Red List Status: Critically Endangered

Habitat destruction and modification has impacted sawfish populations worldwide (Dulvy et al. 2016; Leeney, 2017). To combat the ever declining population numbers the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) declared the family Pristidae to be “among the most threatened elasmobranchs” in the world. The green sawfish currently listed as “Critically Endangered”. The greatest threat is localized extinction from extensive fishing (Kyne et al. 2013). In June 2007, the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES) imposed sanctions for the protection of all sawfish species, making it internationally illegal to trade in sawfish, their rostra, or their fins. The only currently permitted trade is from Australia for public aquaria, in extremely limited quantities. The status of local populations of green sawfishes are unknown. However, they are protected in Australian waters under the Australian Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act.

> Check the status of the green sawfish at the IUCN website.

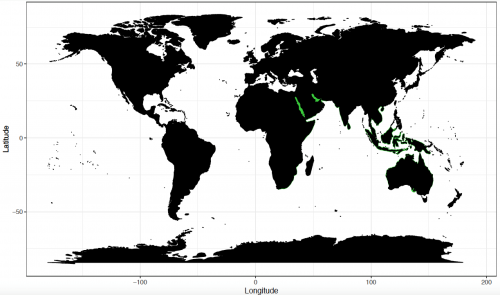

Geographical Distribution

The green sawfish is found in the Indian and western Pacific oceans as well as the east African coastline of the Atlantic (Everett at el., 2015). Ranging to Somalia and the Gulf of Aden up to the Red Sea (Moore, 2014). Local ecological knowledge suggests that, while declining, there is still a population of P. zijsron in the Persian Gulf. From the Gulf of Aden, ranging from the Indian coast to Thailand and south through Indonesia (Last and Stevens, 1994). A 5.13 m (16 ft. 10 in.) specimen was caught off Port Blair in the Andaman Islands in 1967 (Marichamy, 1969). In Australia, occurrences have been reported from Broome (Western Australia) to Sydney (New South Wales), and a single record from Glenelg in South Australia (Last & Stevens, 1994). The Gulf of Carpentaria in Northern Australia may be one of the last viable Pristis populations due its limited human involvement (Peverell, 2005). Lastly, the Pilbara region of Western Australia has been identified as an important pupping ground for the species (Morgan et al., 2015). The green sawfish no longer appears to be common anywhere in its range.

View reported sawfish encounters on a world mapHabitat

Green sawfish live in marine, estuary, and freshwater habitats. Often preferring sand and mud substrates located outside river mouths (Peverell, 2005). The species typically lives in 5.0 m (16.4 feet) of water or less, although adults are found in <100 m depths (Dulvy et al., 2016).

Biology

Distinctive Features

All While they swim much like sharks, sawfish are actually a species of ray. The head is dorso-ventrally flattened with the mouth and gills located under the body and the eyes positioned dorsally. Sawfish are able to breathe while lying on the ocean floor by drawing water into their gills through large holes behind each eye, called spiracles. Their most distinctive feature is their long flat rostral “saw” – studded with rostral teeth along the margins. These “teeth” are set deeply in hard cartilage and do not grow back if the root becomes damaged.

Sawfish can be distinguished from sawsharks (Pristiophorus spp.) by their lack of barbels, dorso-laterally compressed body, ventral gills, similar sized rostral teeth, large size, and preference for shallow coastal habitats. Green sawfish have the longest rostrum of any living species of sawfish, up to 1.66 m (5.4 ft.). They can have 23 and 37 (typically 25-34) rostral teeth per side. Usually one side of the rostrum as a slightly more teeth than other (Last et al., 2016).

Green sawfish is distinguished from the knifetooth sawfish (Anoxypristis cuspidata) primarily by size but also by the shape and number of the rostral teeth (23-37 versus 20-25), presence of dermal denticles over the entire body, and the lack of a developed lower caudal fin lobe (Last et al., 2016).

The Green sawfish is distinguished from the dwarf sawfish (Pristis clavata) by its narrow and moderately tapering rostrum (versus wide-based and strongly tapering), greater number of rostral teeth per side (23-37 versus 18-24), and the lack of a developed lower caudal fin lobe. In addition, the green sawfish reaches a larger maximum size (>7.3 m) than the dwarf sawfish (3.1 m) (Last et al., 2016).

P. zijsron look similar to the smalltooth sawfish (Pristis pectinata), but the origin of their first dorsal fin positioned slightly posterior to the origin of the pelvic fins, versus directly over or slightly anterior to the pelvic fins. The space between last two rostral teeth on a side is about 4-8 times the space between the first two teeth, versus 2-4 times. P. zijsron rostrum less tapered and narrow. In addition, green sawfish have a greater average number of rostral teeth per side than smalltooth sawfish, and have a green body color, versus brown or bluish-gray. Rostra of very young green sawfish are similar to that of the smalltooth sawfish, but whole specimens may be distinguished based on the positioning of the first dorsal fin slightly posterior to the origin of the pelvic fins, versus directly over or slightly anterior to the pelvic fins (Last et al., 2016).

Green sawfish are distinguished from the largetooth sawfish (Pristis pristis) by geographic range. Being found in the Indian and western Pacific oceans versus the western central Atlantic and eastern Pacific oceans. P. zijsron possess a greater number of rostral teeth per side, 23-37 versus 14-24. Their rostrum are narrow and tapering rostrum, versus the wide-based and strongly tapered largetooth rostrum. The first dorsal fin P. pristis originating of slightly posterior to its pectoral fins. Additionally, they lack a lower caudal fin lobe and the slender build of the P. zijsron (Last et al., 2016).

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Rostral Tooth Count | Distribution | Other Distinguishing Features |

| Smalltooth sawfish | Pristis pectinata | 20-30 | Atlantic Ocean | common off the coasts of Florida |

| Largetooth sawfish | Pristis pristis | 14-24 | Global | teeth evenly spaced; rostrum short and wide |

| Green sawfish | Pristis zijsron | 23-37 | Indo-West Pacific Ocean | green in color |

| Dwarf Sawfish | Pristis clavata | 18-24 | Indo-West Pacific Ocean | teeth evenly spaced |

| Knifetooth Sawfish | Anoxypristis cuspidata | 16-26 | West Pacific Ocean | rostral teeth missing at the base of rostrum |

Green sawfish can be easily distinguished from other sawfish by its size and rostral teeth count and orientation (See table) (Last et al., 2016).

Coloration

The dorsal surface of green sawfish is greenish-brown or olive, with yellow-grey dorsal fins. Their rostral teeth are typically a dirty cream or yellow, contrasting with the darker hue of their dorsal rostrum. The lateral sides are yellowish in color. The ventral surface of the body is a creamy white. The eyes are gray to silver with black pupils (Last et al., 2016).

Dentition

Green sawfish have many rows of small close-set rounded cusp teeth in both jaws.

Denticles

Flat, rounded crown denticles cover the entire body. Denticles are similar through all development stages, although larger individuals exhibit a more pronounced crown. Like other Pristis species, zijsron have monocuspidate denticles which uniformly cover the body, as opposed to the tricuspidate denticles found in Anoxypristis (Deynat, 2005). Denticles along the posterior portion of the body are more elongate and convex, while the ventral surface denticles are smaller and pavement-like (Deynat, 2005). A mid-dorsal keel, composed of large specialized dermal denticles, extends from just beyond the spiracles to the base of the second dorsal fin. This dorsal keel appears darker in fetuses.

Size, Age & Growth

Maximum size of P. zijsron has been reported as 7.3 m (24.0 ft.) total length (Last et al., 2016). The green sawfish appears to grow longer than any other living sawfish species. Size at birth is 76 cm (2.5 ft.) (Eschmeyer et al., 1998). Males reach maturity at less than 4.3 m (14.1 ft.) (Last and Stevens, 1994). Females are estimated to reach maturity at 9 years of age (Dulvy et al. 2016). A post-partum female green sawfish measured 3.8 m (12.5 ft.), recorded from the Gulf of Carpentaria (Australia), leading researchers to propose female reach maturity before males. This is the longest living sawfish species, with a lifespan greater than 50 years (Dulvy et al. 2016).

Food Habits

All sawfish swing their rostrum in a side-to-side motion to dislodge invertebrates from substrate and to stun schooling fishes. Prey items of the P. zijsron have not been reported, but likely include small schooling fishes, squids, and crustaceans such as crabs and shrimps (Last et al., 2016).

Reproduction

All sawfishes, have aplacental yolk sac viviparity (Stevens et al., 2005). The embryos are nourished only by their yolk sac which provides all the energy needed for them to develop into fully functional young in utero before they are born. Parturition occurs during the monsoon season (December-March) in the Northern Australia, though data are sparse (Peverell, 2010). Gestation length is unknown, but the largetooth sawfish have a five month pregnancy, and only breed every other year (Campagno & Last, 1999). Red Sea green sawfish brood sizes range from 2 to 12. In Australia, up to 12 young are born during the wet season (January through July) (Peverell, 2010; Morgan et al. 2010, 2011). Size at birth has been reported as ranging from 60−80 cm (Morgan et al. 2015). The saw teeth of young sawfish are covered in a sheath of tissue, until after birth so as not to injure the mother (Walker, 2003; FSUCML. 2016). Young green sawfish rostral teeth reach their full size proportionate to the size of the rostrum soon after birth.

Predators

Although adult green sawfish have little or no natural enemies, part of a large specimen was found in the stomach of a 3.0 m (10 ft) total length tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) caught in the Great Barrier Reef. Other predators of the green sawfish may include bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas), scalloped hammerheads (Sphyrna lewini) and saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus). When entangled in nets, this species is vulnerable to predation.

Parasites

The The parasites Nonacotyle pristis, Neoheterocotyle darwinensis, and Pristonchocotyle papuensis (Hexabothriidae) inhabit the gills of other sawfishes off Darwin, Australia and in Papua New Guinea; and may also use the green sawfish as a host. The copepod Ergasilus sp. (Ergasilidae) inhabits the gills of the freshwater sawfish in the Daly River (Australia), and may target green sawfish as well. Other species that target the green sawfish as a host include monogenean helminths such as Erpocotyle caribbensis and Pristonchocotyle intermedia. Other likely parasites include nematodes, protozoans, and trematodes. Confirmed parasites for zijsron are the Anasakis nematodes as well as several species of tapeworm: Fossobothrium perplexum (found in the spiral valves of zijsron as well as Anoxypristis cuspidata) (Beveridge & Campbell, 2005), Pterobothrium acanthotruncatum, and Pterobothrium australiense (Beverridge et al., 2014). In captivity, the green sawfish is susceptible to heavy infestations of trematodes, which can cover the body and cause irritation.

Taxonomy

The green sawfish was first described by the industrious European ichthyologist Pieter Bleeker in 1851 while residing in Java. Bleeker lived in the East Indies for nearly two decades, which enabled him to collect and describe roughly 1,300 fishes of Indonesia, including the green sawfish. A rostrum measuring 99.1 cm (39 inches) long was taken from a specimen captured in a Borneo river and saved as an example of the species (termed ‘type specimen’). This rostrum is currently housed at the Nationaal Natuurhistorische Museum in Leiden, Netherlands. The valid scientific name of the green sawfish is Pristis zijsron Bleeker, 1851. Synonyms for the green sawfish include a misidentification (Pristis pectinataLatham, 1794), an invalid species (Pristis leptodon Duméril, 1865), and several misspellings (Pristis zisron Bleeker, 1851, Pristis zyrson Bleeker, 1851, and Pristis zysross Bleeker, 1851). The generic name Pristis is Greek for “saw”. It is unclear as to what the specific name zijsron was derived from, and it does not appear to be named after a person or a place. The suffix -on is Greek, however the remainder of the specific name zijsron does not appear Greek. The derivation of the name zijsron continues to be a mystery.

References

Act, B.C., 2011. Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

Beveridge, I., Bray, R.A., Cribb, T.H. and Justine, J.L., 2014. Diversity of trypanorhynch metacestodes in teleost fishes from coral reefs off eastern Australia and New Caledonia. Parasite, 21.

Beveridge, I. and Campbell, R.A., 2005. Three new genera of trypanorhynch cestodes from Australian elasmobranch fishes. Systematic Parasitology, 60(3), pp.211-224.

Bleeker, P., 1851a. Bijdrage tot de kennis der ichthyologische fauna van Borneo, met beschrijving van 16 nieuwe soorten van zoetwatervisschen. Natuurkundig Tijdschrchrift voor Nederlndsch Indië, I: 1-16. (In Dutch).

Bleeker, P., 1851b. Vijfde bijdrage tot de kennis der ichthyologische fauna van Borneo, met beschrijving van eenige nieuwe soorten van zoetwatervisschen. Natuurkundig Tijdschrchrift voor Nederlandsch Indië, II: 415-442. (In Dutch).

Compagno. L.J.V. and Last, P.R., 1999. Batoid fishes, chimaeras and bony fishes part 1 (Elopidae to Linophrynidae). FAO species identification guide for fishery purposes. Volume 3, pp. 1411-1417.

Dulvy, N.K., Davidson, L.N., Kyne, P.M., Simpfendorfer, C.A., Harrison, L.R., Carlson, J.K. and Fordham, S.V., 2016. Ghosts of the coast: global extinction risk and conservation of sawfishes. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 26(1), pp.134-153.

Deynat, P.P., 2005. New data on the systematics and interrelationships of sawfishes (Elasmobranchii, Batoidea, Pristiformes). Journal of Fish Biology, 66(5), pp.1447-1458.

Eschmeyer, W.N., Ferraris, C.J. and Hoang, M.D., 1998. Catalog of fishes (Vol. 1, No. 2, p. 3). San Francisco: California Academy of Sciences.

Everett, B.I., Cliff, G., Dudley, S.F.J., Wintner, S.P. and Van der Elst, R.P., 2015. Do sawfish Pristis spp. represent South Africa’s first local extirpation of marine elasmobranchs in the modern era?. African journal of marine science, 37(2), pp.275-284.

Field, I.C., Charters, R., Buckworth, R.C., Meekan, M.G. and Bradshaw, C., 2008. Distribution and abundance of Glyphis and sawfishes in northern Australia and their potential interactions with commercial fisheries.

FSUCML. 2016. FSUCML scores another scientific first: Dr. Dean Grubbs and colleagues document and assist pregnant sawfish give birth in the wild. Florida State University, Coastal and Marine Laboratory.

Guilford, Gwynn., 2014. Fishing, Chinese Medicine, and a Crazy-Looking Snout Are Driving Sawfish to Extinction. Quartz, qz.com/217333/fishing-chinese-medicine-and-a-crazy-looking-snout-are-driving-sawfish-to-extinction/.

Johnston, T.H. and Mawson, P.M., 1951. Report on some parasitic nematodes from the Australian Museum. Records of the Australian Museum, 22(4), pp.289-297.

Kyne, P.M., Carlson, J. & Smith, K. 2013. Pristis pristis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013: e.T18584848A18620395.

Last, P.R. and Stevens, J.D., 1994. Sharks and Rays of Australia, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, Australia. pp. 513.

Last, P., Naylor, G., Séret, B., White, W. de Carvalho, M. and Stehmann, M. eds., 2016. Rays of the World. Csiro Publishing.

Leeney, R.H., 2017. Are sawfishes still present in Mozambique? A baseline ecological study. PeerJ, 5, p.e2950.

Marichamy, R., 1969. On a large-sized green saw fish Pristis zijsron Bleeker landed at Port Blair, Andamans. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of India, 10(2), pp.394-394.

Moore, A.B., 2015. A review of sawfishes (Pristidae) in the Arabian region: diversity, distribution, and functional extinction of large and historically abundant marine vertebrates. Aquatic conservation: marine and freshwater ecosystems, 25(5), pp.656-677.

Morgan, D.L., Allen, M.G., Ebner, B.C., Whitty, J.M. and Beatty, S.J., 2015. Discovery of a pupping site and nursery for critically endangered green sawfish Pristis zijsron. Journal of Fish Biology, 86(5), pp.1658-1663.

Morgan, D.L., Whitty, J.M., Phillips, N.M., 2010. Endangered sawfishes and river sharks in Western Australia. Report to Woodside Energy Ltd. WEL JA0006RH0085 Rev 0. Centre for Fish & Fisheries Research, Murdoch University, Perth

Morgan DL, Whitty JM, Phillips NM, Thorburn DC, Chaplin JA, McAuley R 2011. North-western Australia as a hotspot for endangered elasmobranchs with particular reference to sawfishes and the Northern River shark. J R Soc West Aust 94: 345−358

Morgan, D.L., Allen, M.G., Ebner B.C., Whitty, J.M., Beatty, S.J. 2015. Discovery of a pupping site and nursery for critically endangered green sawfish Pristis zijsron. J Fish Biol. 86: 1658−1663.

Peverell, S.C., 2005. Distribution of sawfishes (Pristidae) in the Queensland Gulf of Carpentaria, Australia, with notes on sawfish ecology. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 73(4), pp.391-402.

Peverell, S.C., 2010. Sawfish (Pristidae) of the Gulf of Carpentaria, Queensland, Australia. Doctoral dissertation, James Cook University.

Shamsi, S., 2014. Recent advances in our knowledge of Australian anisakid nematodes. International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife, 3(2), pp.178-187.

Stevens, J.D., R.D. Pillans, and Salini, J. 2005. Conservation Assessment of Glyphis sp. A (Speartooth Shark), Glyphis sp. C (Northern River Shark), Pristis microdon (Freshwater Sawfish) and Pristis zijsron (Green Sawfish). Hobart, Tasmania: CSIRO Marine Research.

Walker, S.M. 2003. Rays. Carolrhoda Books, Inc. p. 38. ISBN 1-57505-172-9.

Prepared by Tyler Bowling and Gavin Naylor, 2018