The Rainforest Exhibits at the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity at the Florida Museum of Natural History features many species of Lepidoptera, but perhaps none are as impressive as Attacus atlas, commonly known as the Atlas moth. This gentle giant is among the world’s largest moths, sporting a wingspan that can reach nearly a foot long.

This moth is native to the forests of Southeastern Asia, where its larvae feed on a variety of trees in the rainforest. The larvae have also been recorded feasting on avocado, guava, camphor, cinnamon, and mango trees. In captivity, it has been reared on ash, lilac, cherry, privet, and ailanthus, also known as trees of heaven. Atlas Moth caterpillars develop in 4-6 weeks. The huge caterpillars need to store as much energy as possible before spinning a thick and extremely durable cocoon which will protect its pupa from predators. Like all members of the family Saturniidae, the adult Atlas Moth, does not feed, and the proboscis – the tube-like mouthpart that is so characteristic of butterflies and many moths, is not developed.

Adult Atlas Moths only live for about a week, so time is of the essence. When the sun goes down, newly hatched females release sex pheromones to attract males. While a female will only mate once, some males might mate more than once. In addition to their size and wing shape, males differ from females by their feathery antennae. These comb-shaped structures evolved to increase the surface area for the pheromone receptors, which allow the male to find females over long distances. After several hours of mating, egg-laying can start immediately, as the eggs are fully formed inside the female’s abdomen when the moth emerges from the cocoon.

While the moths are palatable to predators, it is likely that their large size allows them to avoid predation by smaller bat species. During the day, the moths rely on camouflage and stillness for protection from birds, though for a smaller bird these moths are likely a formidable prey which is not easy to subdue. Though this hypothesis has not been experimentally tested, it has been proposed that the Atlas Moth also gains protection from a startling form of mimicry: the colorful pattern of the forewing resembling the head of a snake. When disturbed, Atlas moths are known to drop to the ground and flap their wings, perhaps imitating the movement of a snake!

In their native habitats in Southeastern Asia, Atlas Moths are loved not just for their beauty but also as a source of fagara silk. Silk is spun and woven into items like purses, shoes, and clothing. Cocoons themselves can be used for crafts as they have beautiful shiny brown colors! Unlike the vast commercialization of mulberry silk from Bombyx mori silkworms, or Tussar silks derived from saturniids of the genus Antheraea, the production of fagara silk is much more niche. The thick, brown husks of Atlas Moth cocoons do not provide the same yield of fine, smooth silk as that of the silkworms. Because of this, Atlas Moths are allowed to pupate and hatch before their cocoons are harvested for silk production, creating a much smaller and sustainable fagara silk industry.

To find out more about Atlas Moths, I spoke to Ingrith Martinez of the Butterfly Rainforest Exhibit at the Florida Museum of Natural History. Most of Atlas Moth cocoons they receive come from a supplier based in the Philippines, with 705 specimens shipped to the Museum in 2024. The Rainforest is approved by the United States Department of Agriculture to receive the cocoons, where they are housed in a specialized quarantine facility that ensures that the cocoons are free of parasitoids and that moths, once they hatch, cannot escape. Because these moths feed on a wide variety of fruit trees, they are considered potential pests and should not be otherwise imported by individuals into the United States. Once hatched, the moths are displayed and can be viewed through the window of the quarantine lab or may be transferred into the screened Rainforest Exhibit. They are a common source of awe among the public visiting this screened enclosure, where exotic butterflies, plants, and even some tropical birds can be enjoyed while traversing a winding path surrounded by flowers nestled among moss-covered limestone rocks and water features. Unlike butterflies that flutter around the visitors feeding on flowers, Atlas Moths sit still on tree trunks and may give the visitors an impression that they are fake.

Only male Atlas Moths are placed in the Rainforest Exhibit, while the females are displayed through the window of the lab where they emerge. I asked why not the other way around? It turns out that, as in many moth species, female Atlas Moths will still lay eggs even if they did not mate. These unfertilized eggs may end up being placed by the moths on walls, tables, and tree trunks.

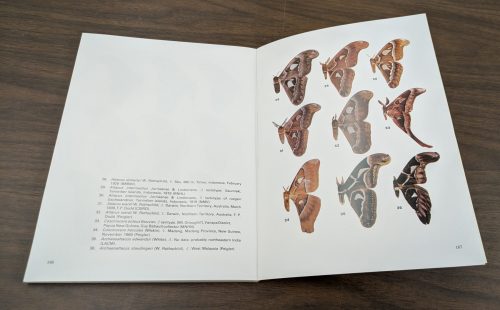

There are many species of moths in the genus Attacus, and their taxonomy continues to be refined. The species can be hard to identify, so the location where they occur, their internal structures (such as male genitalia), and, of course, the moth’s DNA, may be more informative than their external features. Some of the distinguishing characters nevertheless can be found in the wing coloration and wing shape. One of the species commonly confused with Atlas Moth is Lorquin’s Atlas Moth, Attacus lorquinii, which is endemic to the Philippines. It can be distinguished from Attacus atlas by the pink coloring at its wing tip as opposed to the bright yellow hue of Atlas Moth.

One of the McGuire Center’s long time research associates and specimen donors, Richard Peigler, assessed the taxonomy of the genus in his monograph published in 1989. The McGuire Center’s research collections house several Attacus species, with Atlas Moth being the most common. These specimens are the source of data for research conducted at the McGuire Center. For instance, the Kawahara lab delves into the evolution and genetics of Saturniidae and frequently utilizes tissues from specimens for extracting and analyzing DNA. Specimens also are studied using computer vision morphometric techniques, which can quantify wing shape and color differences.

Understanding the evolutionary history of the genus and its taxonomy aids in identifying populations that are of conservation concern. While Attacus atlas is not considered endangered, its Australian relative, Attacus wardi, is currently under threat due to habitat destruction. While not much is known about A. wardi and other rare species of Attacus, studying traits of the closely related Atlas Moth, such as brood size and reproduction rate, could provide valuable information for conservation efforts. Elsewhere, exciting cutting-edge research on medical uses of silks has also tapped into Atlas Moth as a model species, contributing to a field that has been dominated by Domesticated Silk Moth studies. The species also continues to be a larger-than-life source of awe and curiosity to people fascinated by animals and are a beautiful reminder of the importance of protecting our world’s biodiversity.

_________________________

Sources: Andrei Sourakov, Lepidoptera Collections Coordinator and Ingrith Martinez, Butterfly Rainforest.

Contact: Miranda Guse, miranda.guse@ufl.edu

_________________________

References

Peigler, Richard S. (1989). Attacus: A Revision of the Indo-Australian Genus. Lepidoptera Research Foundation, Inc. Beverly Hills, California. 167 pp.

_________________________

Florida Museum Links:

Video: Atlas Moth in the Butterfly Rainforest Exhibit of the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Yes, they are real (from the Florida Museum exhibits)

Moths with larger hindwings and longer tails are best at deflecting bats