The McGuire Center and University of Florida have a deep history of studying the extraordinary phenomenon of Monarch migration, where millions of Monarch butterflies fly each year to congregate in specific overwintering sites. Under the leadership of its founding director, Thomas Emmel (1941–2018), the McGuire Center has played a variety of roles in Monarch conservation efforts, particularly through research, education, and ecotourism to Mexican overwintering sites. In fact, Emmel, who had a profound knowledge of the phenomenon, pioneered ecotourism to these overwintering sites, leading numerous expeditions to Angangueo, Mexico, over several decades. These tours, often involving students and museum supporters, were designed to promote appreciation and awareness surrounding the unique process of migration, while also bringing attention to the local community.

The University of Florida has been on the forefront of research pertaining to Monarch butterfly migration and overwintering sites, engaging scientists, staff, and students alike. One of UF’s former professors, Lincoln Brower (1931–2018), dedicated over six decades to studying the Monarch’s biology and conservation. He led research teams studying the ecology of overwintering sites in Michoacán, Mexico, and advocated for the protection of oyamel fir forests from logging. It was Dr. Brower who attracted the attention of the public, both in the United States and in Mexico, to Monarch migration as an endangered phenomenon. Brower also worked with the local community in Mexico to protect the forest.

Tom Emmel, who for decades worked with Brower in UF’s Zoology (now Biology) Department, recognized ecotourism as a driving force for local conservation, and began bringing groups to Michoacán at the beginning of this century. For many years, he led several tours in the spring to the overwintering sites and even brought community members for visits from Angangueo in Mexico to Gainesville, Florida, to establish closer relations between the two towns and between the town’s community and the McGuire Center. He personally sponsored local people from Angangueo to study English at UF’s English Language Institute, which he saw as crucial for successful conservation efforts, because this facilitated the development of foreign ecotourism in the area. When Tom passed away in 2018, the role of leading the trips passed from him to Andrei Sourakov and Jaret Daniels at the McGuire Center, who have since led numerous museum-sponsored trips to the sites. While the COVID-19 pandemic briefly affected ecotourism to the area, it has fully resurged subsequently, with tens of thousands of mostly Mexican tourists visiting every year.

“This is one of the experiences that not only I, but all my three kids, have greatly enjoyed over the years. It is an easy, pleasant trip during which one can experience the best of the magnificent nature, culture, history, and cuisine of Mexico, all in the span of five days,” said Sourakov, who led six trips to the area between 2004 and 2025. “While Mexico is changing a lot, becoming more and more developed, the town of Angangueo in Michoacán retains its charm, and it is one of my favorite places to visit.”

Upcoming trips to Mexico led by McGuire Center staffThose interested in seeing this unique wildlife spectacle can join tours to Mexico, such as the upcoming trip led by McGuire Center staff and sponsored by the Florida Museum of Natural History in February 2026!

|

After the retirement of Lincoln Brower from the department of Zoology, Monarch research at the University of Florida has nevertheless continued. Jaret Daniels, one of the curators at the McGuire Center, who currently also serves as Interim Director for Exhibits and Public Programs of the Florida Museum of Natural History, oversees research and outreach regarding the conservation of at-risk butterflies and pollinators, including the Monarch. His lab works on conservation and recovery across the United States, highlighting the importance of native milkweeds (the Monarch’s host plants) and nectar plants for the migratory generation. With his colleagues at UF’s Entomology and Nematology Department, such as Adam Dale, Jaret also advises students and postdocs on projects related to research on Monarchs and milkweeds. Other researchers affiliated with the McGuire Center, such as Cristina Dockx, have published studies that focus on the nuances of Monarch migration routes, finding evidence that some Florida Monarchs migrate south to Cuba. Members of the Marta Wayne’s lab at UF’s Biology department studied migration using genomic and isotope methodologies. Court Whelan, a former graduate student at the McGuire Center and UF’s Entomology Department, not only co-led educational trips to the Mexican overwintering sites but also described how ecotourism has directly enabled conservation of approximately 56 thousand hectares of overwintering habitat. The Kawahara lab at the McGuire Center has led several studies of butterfly evolution, which have allowed us to better understand when milkweed butterflies in general, and the genus Danaus in particular, evolved. A study on caterpillar mimicry led by Keith Willmott involved, among other species, the Monarchs and their relatives, suggesting convergent evolution in caterpillar patterns. Moreover, one of Sourakov’s studies on butterfly wing patterns included Monarchs, adding to our understanding of what lies behind their unique and easily recognizable coloration. Such collective efforts at the University of Florida have helped to advance our understanding of Monarchs’ biology, evolution, and migration.

To expand research efforts into conservation, protection, and behavior of Monarchs, it is first important to understand just how Monarch migration works. Monarchs, whose scientific name is Danaus plexippus, flutter their way across the vast expanse of North America for journeys of up to 2,000-3,000-miles. Monarch butterflies in the Eastern part of North America generally migrate on a consistent routine, beginning their trip in late summer/fall from the United States or Canada and heading south to Mexico in the fall. A few months later, in the spring, the same generation begins to fly back north, and the subsequent generations continue populating the continent. In the fall, the cycle repeats itself. Due to a dramatic change in gene expression and hormones, this “super generation” of butterflies that ultimately end up flying to Mexico lives eight times longer than normal butterfly generations!

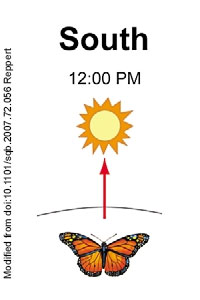

Much of our understanding of the Monarch’s biology came, unexpectedly, from a neuroscientist, Steven Reppert, at the University of Massachusetts’s Medical School, who brought new tools to butterfly research. Monarchs use factors like sunlight, magnetic fields, and landscape cues to navigate towards their destination. This endeavor is dependent on the Monarch’s neurological toolkit, relying primarily on a time-compensated sun compass. For this compass to work, their eyes detect skylight cues such as the sun’s position and ultraviolet polarization patterns; then, this information is integrated inside the brain’s central complex and corrected for the time of day by circadian clocks located in their antennae. As a backup, Monarchs have an inclination-based magnetic compass, which senses the angle of Earth’s magnetic field and is crucial for navigating during periods of cloudy weather. Additionally, elements such as wind patterns, atmospheric pressure, and possibly even their sense of smell, are also integrated into this system.  Thanks to the advances in genomics, researchers have determined that migration is also guided by an ingrained genetic program, as evidenced by distinct gene expression and microRNA activity between migratory and non-migratory Monarchs. Tools like CRISPR/Cas9 have even identified specific genes, such as cryptochrome 2, as essential components of the circadian clock mechanism that underpins their navigational systems.

Thanks to the advances in genomics, researchers have determined that migration is also guided by an ingrained genetic program, as evidenced by distinct gene expression and microRNA activity between migratory and non-migratory Monarchs. Tools like CRISPR/Cas9 have even identified specific genes, such as cryptochrome 2, as essential components of the circadian clock mechanism that underpins their navigational systems.

Monarch butterflies are typically divided into two migratory populations: the eastern population, which overwinters in Mexico, and the western population, which overwinters in Coastal California. The two populations are not genetically distinctive as they are likely mixed during migration process. Interestingly, not all Monarchs migrate; there are also sedentary populations in other parts of the world and in certain parts of North America that do not undertake this journey. However, their closest relatives, the Southern Monarch, Danaus erippus, found in southern South America, is also migratory, and so are many other milkweed butterflies. Hybridization experiments and cuticular hydrocarbon analyses were performed at the Department of Entomology of the University of Florida by Mirian Hay-Roe and James Nation, who have determined that Danaus plexippus and D. erippus are separate, reproductively isolated species. Our knowledge about the routes of the Southern Monarch’s migration is mostly based on studies by Stephen Malcolm, who worked on Monarch chemical ecology at the University of Florida as a postdoc in Brower’s lab in 1980s. Steve’s knowledge of techniques and his dedication account for much of Brower’s success in understanding how Monarch butterflies sequester cardenolides from their larval host plants – milkweeds of the genus Asclepias – for use in defense against predation.

Just as people take breaks at rest stops on road trips, Monarchs stop every now and then to refuel on nectar, and they also rest overnight in trees. After all, they need to replenish their energy so that they can fly the next morning with renewed strength! Remarkably, they not only do not lose, but actually gain weight on the journey south, accumulating fat that will help them survive the winter. Over winter, once they are in Mexico, many butterflies form huge clumps in the centrally located oyamel fir forests high in the mountains, and they periodically fly down to drink and nectar along the streams in the forest, where this tropical species has found a safe winter haven.

“While there are numerous videos and photos online of Monarch migration, there is nothing like being there in person, being surrounded by millions of flying butterflies, hearing the noise of their wings, and smelling the oyamel forest,” Sourakov said. “Migration can rightly be considered one of the greatest shows on Earth, and I hope that more people will be able to see it in person.”

Watch interview about Monarch Migration with Thomas C. Emmel, the Founding Director of the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity:

Related Links:

- A kaleidoscope of monarchs: Marveling at one of nature’s greatest journeys – Research News by Florida Museum’s Kristen Grace with Halle Marchese and Natalie van Hoose • October 29, 2019

- Monarch Migration Meditations by Andrei Sourakov, March 3, 2020.

Source: Andrei Sourakov, asourakov@flmnh.ufl.edu

Media contact: Kay Johnson, kayliejohnson@ufl.edu

\

\