Our horses breathed deep but kept a steady pace as we ascended to 10,000 feet above sea level, scanning the greenery for the first glimpse of orange.

The air was crisp, the February sun warm on our backs – perfect conditions for butterflies awakening from a chilly night’s slumber.

Every fall, hundreds of millions of monarch butterflies, Danaus plexippus, travel nearly 3,000 miles across the U.S. to the sacred fir forests of Central Mexico to wait for winter to soften into spring. The journey south is made by a single generation – an impressive feat in itself – but the return journey is completed by multiple generations. Our hope on this trip, an ecotourism experience organized by Holbrook Travel and led by Florida Museum of Natural History researchers, was to witness these tiny travelers begin to wend their way back north.

But with monarchs in decline, we didn’t know what to expect.

At El Rosario, the largest of five monarch sanctuaries in the region and home to about 40% of the overwintering population, we began to spot monarchs feeding on wild mountain flowers. As the path wound inside the forest, we tilted our heads to see clusters of monarchs hanging in the canopy. The butterflies became thicker, covering the ground and trees and bumping into us. A trail that broke through the trees and down the mountain was filled with a river of monarchs, descending from the colony to soak up the sun and drink nectar. They were so thick we could hear their wings beating. We stopped to marvel at this sight and sound, many of us moved to tears.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

“What we saw was a natural phenomenon that becomes an emotional, almost spiritual experience,” said Jaret Daniels, director of the Florida Museum’s McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity and one of the trip’s leaders. “You cannot help but be moved by seeing that many butterflies flying around you. That’s what monarchs can bring.”

Monarchs face a number of challenges, including agricultural pesticides, widespread habitat loss and climate change. California’s populations are dwindling and Florida saw an 80% decline in monarchs since 2005. Once spread over 44 acres of forest in Mexico, the butterflies only overwintered on about 6 acres in 2018, according to Monarch Watch.

But for a brief moment, Mexico’s monarchs were back in force, with an estimated 144% increase in area occupied by overwintering monarchs over the previous year.

“We were really able to experience this latest uptick in numbers firsthand, and the numbers were spectacular,” said Daniels, who is also a professor in the University of Florida’s department of entomology and nematology. “The activity was phenomenal – hundreds of millions of butterflies would literally envelope you. It’s really the only place in the world where you can hear butterflies flying. The stream of activity when we were in the colonies never stopped.”

But Daniels cautioned against taking the recent increase, which only applies to one of three North American monarch populations, as a sign of healthy colonies. Monarch populations can often fluctuate.

“One year doesn’t make a trend,” Daniels said. “We need to be looking at this in the long term. Are the numbers going to recover and tick upwards or is this a blip on the radar?”

Preserving natural and cultural heritage

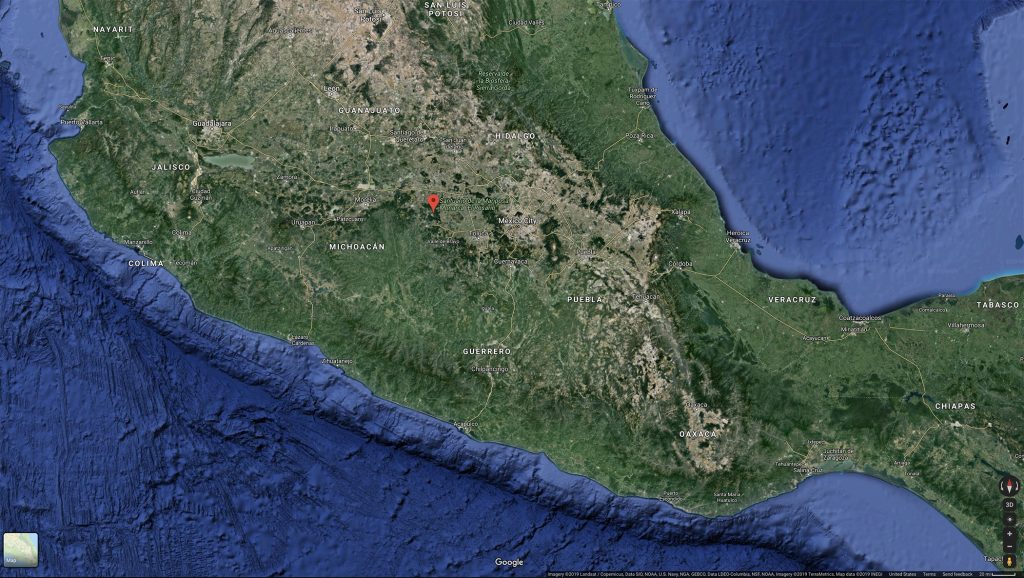

About 217 square miles of Mexico’s fir forests are recognized as a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization World Heritage Site due to the strong relationship between Mexican culture and the monarch migration.

The monarchs’ arrival between late October and early November coincides with the Mexican holiday Dia de los Muertos, or “Day of the Dead.” Temporary altars, called ofrendas, are decorated with representations of earth, wind, fire and water to nourish and guide visiting spirits of loved ones – said to be carried in with the monarchs.

In the small town of Angangueo, whose Purepecha name loosely translates to “the town between the mountains,” striking the delicate balance between local livelihoods, healthy fir forests and the monarch populations that depend on the region is critical. As the town’s mineral mining industry dried up, residents struggled to find income, and illegal logging of fir forests led to devastating habitat loss for the monarchs.

Over time, and with the help of local government and nonprofit agencies, the people of Angangueo put a premium on protecting the monarch and now rely on the global popularity of the butterfly’s migration to help their local economy. But the relationship between conserving wildlife and meeting human needs can be tenuous.

“Every year I’ve visited, there’s a steady creep of farms and communities up the mountainside,” said Florida Museum Director and trip leader Douglas Jones. “It’s a balance between preserving natural habitats and the farmland people depend on. Understanding the dynamics of the people in the community is really essential in planning out how we’re going to keep monarch sanctuaries healthy and vital.”

A population in peril

Mexico’s fir forests are modern remnants of boreal forests that extended south during glacial periods, but retreated north as global temperatures increased over millions of years. Now limited to the high elevation peaks of Mexico’s Sierra Madre mountains, these towering fir trees can take decades to mature and provide a sheltered microclimate for overwintering monarchs. Although these mountain peaks can be a winter paradise for butterflies, their extremely remote locations often make them accessible to visitors only by horseback or on foot.

But the annual treks to monarch colonies can give researchers key insights into the eastern monarch population, one of three in North America. Mexico’s monarchs are responsible for recolonizing Eastern North America as they journey as far north as Canada. Understanding overwintering numbers in Mexico can help researchers predict what monarch numbers will look like in the U.S., particularly Florida, in the coming year.

“We can use specimen and population data from the wild to better inform our studies,” Daniels said. “We need to pay attention to those numbers so we can better manage and recover monarch populations here in Florida because Florida is sort of the gateway for monarchs to upper East Coast regions.”

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

Researchers also monitor the growth of milkweed, the host plant monarchs depend on for food and depositing their eggs. Milkweed is essential to maintaining healthy monarch numbers during their mating season and replenishing migratory populations returning to the U.S. from Mexico. But climate change is shifting when milkweed blooms and could also endanger the health of Mexico’s fir forests, Daniels said.

“Climate change is a real threat to patterns monarchs have developed over millennia. If the timing in milkweed availability is thrown askew, it’s a significant challenge,” Daniels said. “For their high-elevation overwintering habitats, warming temperatures could also displace the fir forests.”

Daniels said that small-scale conservation efforts, such as planting native milkweed species, cultivating wildlife friendly gardens and leaving rights-of-way and other unused green spaces unmown can help. Conservation and monitoring programs such as Monarch Watch, Journey North and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Save the Monarch initiative also offer opportunities for citizen scientists and communities to contribute to protecting the monarch.

Daniels and Jones said that museum visitors and passionate trip-goers give them hope.

“When I look at my own children and when I see young, enthusiastic kids come into the museum, they really do have a passion for the natural world,” Jones said. “Our museum is responsible for encouraging people to act in environmentally responsible ways, and if seeing monarchs burst forth from trees where they’ve been spending the night doesn’t get your blood pumping about the beauty and wonder and mystery of nature, I don’t know what does.”

Florida couple become monarch outreach specialists

For Green Cove Springs, Florida, residents Bob and Carolyn Warren, protecting monarchs is personal.

The couple cite a chance viewing of the documentary “Flight of the Butterflies” as a transformative experience that made them “decide to do whatever we could to help these winged beauties,” Bob Warren said.

They began raising and releasing monarchs and giving local presentations on their biology and plight. Carolyn Warren reached out to Daniels for education and outreach materials, and after learning he was leading a group tour to Mexico’s monarch sanctuaries, felt it was an opportunity not to be missed.

“On several occasions during the trip, Jaret asked me what I thought about what I was seeing,” Bob Warren said. “Each time I told him to watch Carolyn’s eyes and you can see ‘our’ pure joy and amazement. On the flight back to the U.S., Carolyn and I decided that there were really no words to describe what we had experienced.”

After returning home, the Warrens redoubled their efforts to increase public awareness about monarch butterflies and also joined Monarch Watch and Journey North’s monitoring programs.

“For the first time we have actually tagged some of the monarchs passing through our area,” Bob Warren said. “The trip served to reinforce our desire to promote the preservation of these beautiful creatures. I am no prophet, but one thing I can tell you with certainty: When the butterflies are gone, we will not be far behind.”

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

Jones said ecotourism ventures are critical to educating and inspiring laypeople to join scientists in studying and protecting life on Earth.

“There’s an old adage that you can’t care about something unless you know about it and have been exposed to it, and so for many people, exposure to endangered or threatened species comes from seeing them in the field,” he said. “It’s important for people to get an opportunity to see animals and plants that are endangered so they can sense the problems surrounding them and be poised to act in conservation.”

Sources: Jaret Daniels, jdaniels@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-2022;

Douglas Jones, dsjones@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-1902