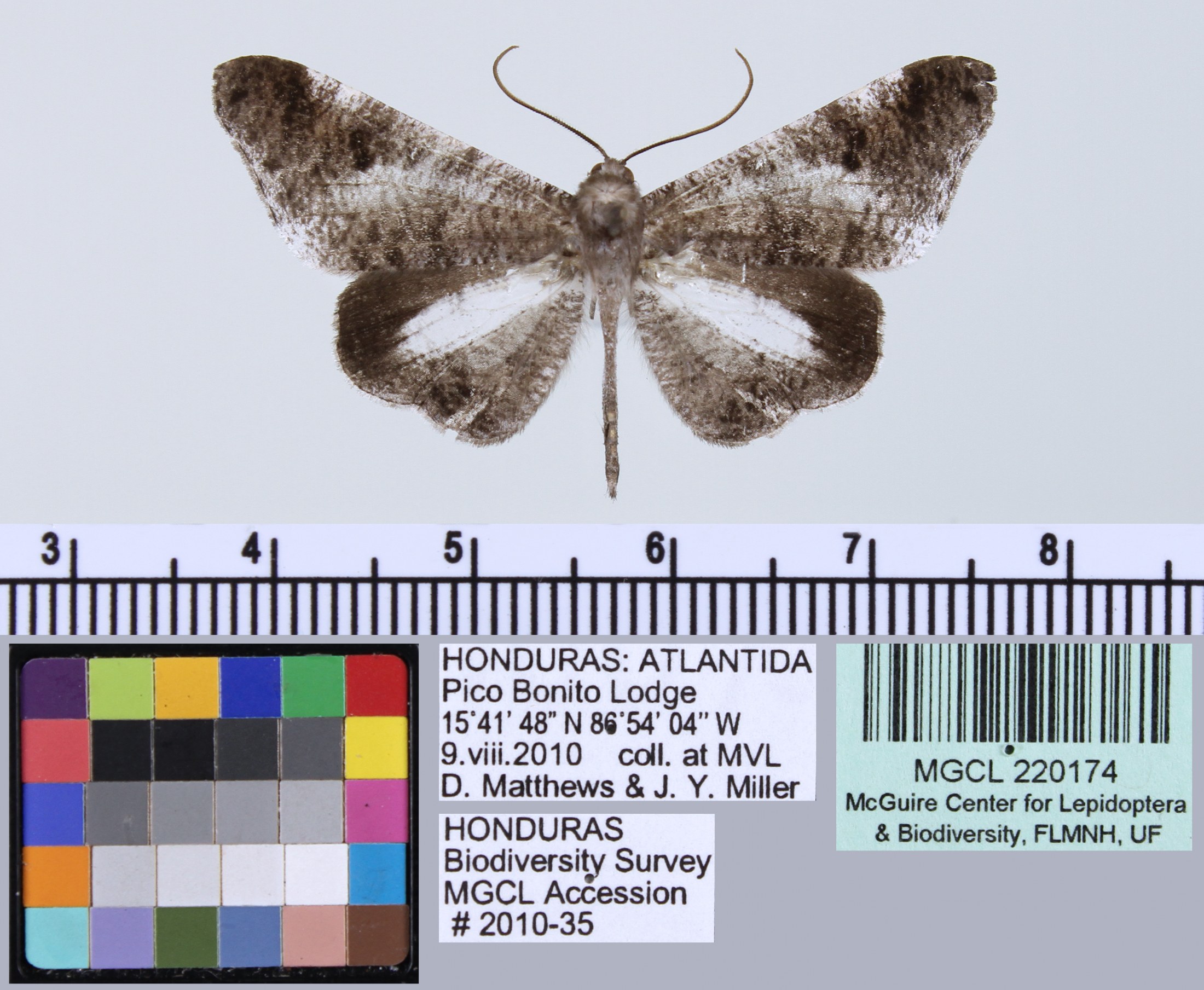

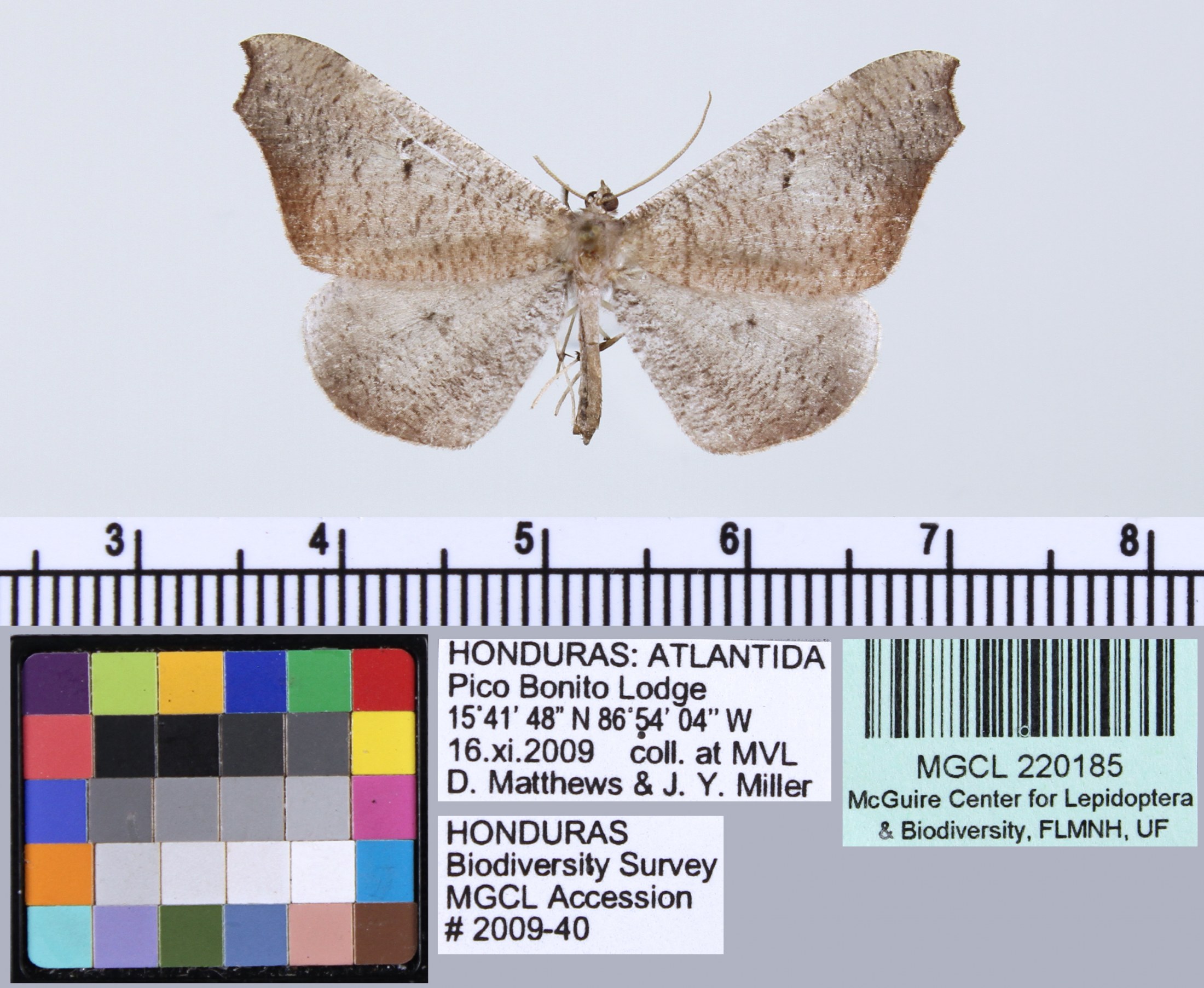

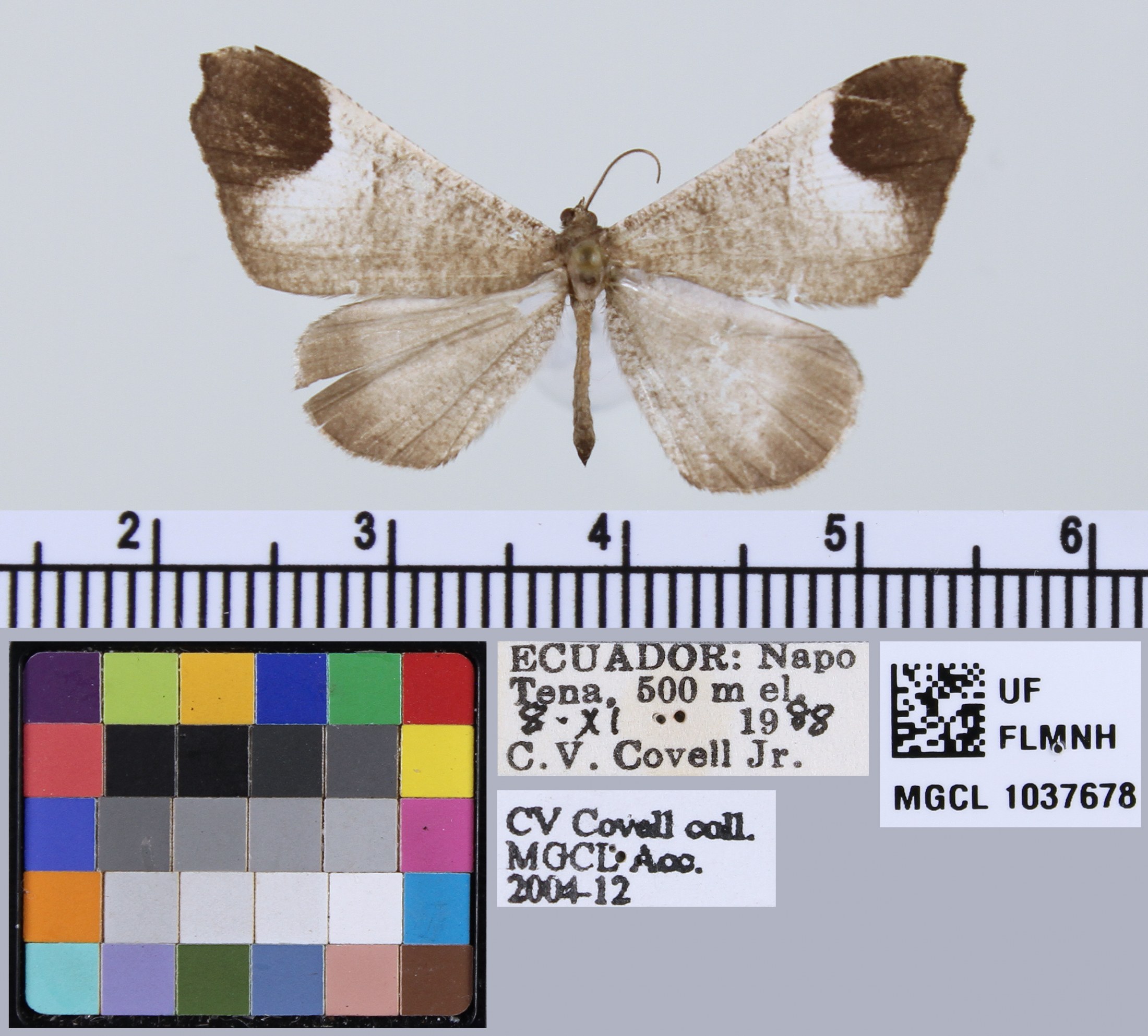

Hedylidae, commonly known as American Moth-butterflies, is a small, little-known family of Lepidoptera. This tropical family, restricted to Central and South America, includes only one genus, Macrosoma, with 36 species. Their common name alludes to their close relationships to butterflies as well as their nocturnal activity and moth-like appearance, with clubless antennae and superficial resemblance to inchworm moths (Geometridae). The caterpillars have long horn-like projections on the head which resemble certain nymphalid butterflies, and unlike geometrids they are not missing any prolegs. Like many butterflies, they have a chrysalis-type pupa which is held in place by a silken girdle and a well-developed cremaster. Hedylid eggs are ribbed and elongate, like those of pierid butterflies.

The behavior and ecology of these “Moth-butterflies” are also remarkable. Hedylids have evolved specialized hearing organs at the base of their forewings to detect the ultrasound calls of bats, a major predator. By contrast, geometrid moths, for example, have hearing organs on the abdomen.

Due to their limited geographic range and low diversity, hedylids have received little scientific attention. Their evolutionary relationships confused taxonomists for decades, especially after 1986, when a study based on detailed morphological characters introduced “a new concept of the butterflies” which proposed that Hedylidae was the sister group (closest relative) to the Papilionoidea (“true butterflies”) with Hesperioidea (“skipper butterflies”) the sister group to Hedyloidea + Papilionoidea.

In 2018, the Kawahara lab and collaborators conducted in-depth DNA analyses of this fascinating family using known genes from 13 specific loci (chromosome locations) so they could determine relationships of the species within the family as well as affirm their relationships to other butterflies. They confirmed the findings of previous molecular studies indicating that Hedylidae are more closely related to skippers than to the other butterfly families. Within Hedylidae, they found three clades (groups) of species nested within two branches of the resulting phylogenetic tree, with Macrosoma tipulata and Macrosoma semiermis each as separate basal branches. This study also examined the distribution of “diel” (24 hour) behavior within the family by mapping the occurrence of nocturnal and diurnal activity on the phylogenetic tree. Rather than a single transition from diurnal to strictly nocturnal behavior in the ancestors of Hedylidae, the study results indicated a more gradual transition to nocturnality with an intermediate step of both nocturnal and diurnal behavior.

Rachit Pratap Singh, a visiting researcher at the Kawahara Lab, is continuing research on this family, working to expand genomic knowledge of hedylids. Together with Yi-Ming Weng, a postdoctoral associate, he has assembled the first complete genome of a hedylid, which includes the complete set of DNA and information about the genes. The focal species for their project is Macrosoma leucophasiata, which is only found in South American rainforests. The genetic makeup of this species is being investigated to further understand hedylid evolutionary history and adaptation to a dark environment. They are also using genomic information from a variety of day- and night-flying Lepidoptera species, with a focus on genes linked to vision. Since hedylids are mostly nocturnal and possess moth-like features, their comparison to moths can help better understand the evolutionary history of these organisms. This marks the first comparative analysis of complete genomes involving these overlooked Moth-butterflies in the context of the evolution of vision genes in butterflies.