After the Seloy-Menéndez fort and town were moved to Anastasia Island in 1566, the area around the Fountain of Youth Park remained a Timucua settlement.

Despite the presence of the Spanish blockhouse “at San Agustín el Viejo”, relations between the Timucua and the Spanish continued to be hostile until at least the early 1570’s. Efforts to convert the Timucua to Christianity began in the vicinity of the former Spanish settlement after 1577, when the first Franciscan friars arrived in Florida. A number of Timucua were baptized, including the Cacica (Chieftainess) of the town of Nombre de Dios, the name given to the Native American town just north of the Spanish city. These first Christian Indians attended Mass in the town of St. Augustine until after 1587, when the first Franciscan mission doctrina, was established at the Nombre de Dios, and was given the same name. Franciscan friar Antonio de Escobedo was assigned there, and helped build the first Nombre de Dios mission church.

In 1934, a gardener who was planting orange trees on the grounds of the Fountain of Youth Park discovered human burials, laid out in the Christian fashion. The owner of the site, Walter B. Fraser, contacted the Smithsonian Institution, and archaeologist J. Ray Dickson subsequently conducted extensive excavations there. Archaeological work since 1934 has shown that the initial site of the Nombre de Dios mission church was in the southwestern section of what is today the Fountain of Youth Park, about 165 meters southwest of the Menendez settlement area.

Dickson located more than 100 burials (for a description and report of that work, see Seaberg, Lillian (1951) Report on the Indian Site at the “Fountain of Youth”. Ms. on file, Florida State Museum, University of Florida, Gainesville. (Reprinted in Spanish St. Augustine: A Sourcebook for America’s Ancient City. edited by K. Deagan. 1991, Garland Press.). They were nearly all interred in a traditional Christian pattern, extended with their faces toward the east. Some intruded upon others. The Christian burial ground was placed on the site of an earlier Timucua village midden, but the materials associated with the burials (mostly glass beads) dated to the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

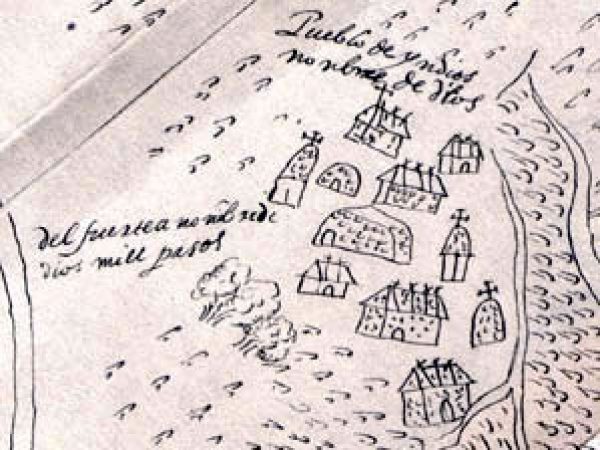

De Meestas map of St. Augustine, ca. 1593, showing the Indian pueblo of Nombre de Dios, the fort and the Spanish town

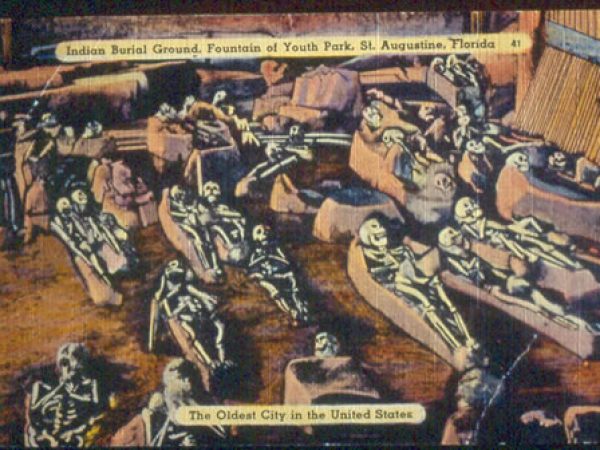

De Meestas map of St. Augustine, ca. 1593, showing the Indian pueblo of Nombre de Dios, the fort and the Spanish town Postcard, ca. 1935, showing Christian burials at the Fountain of Youth Park

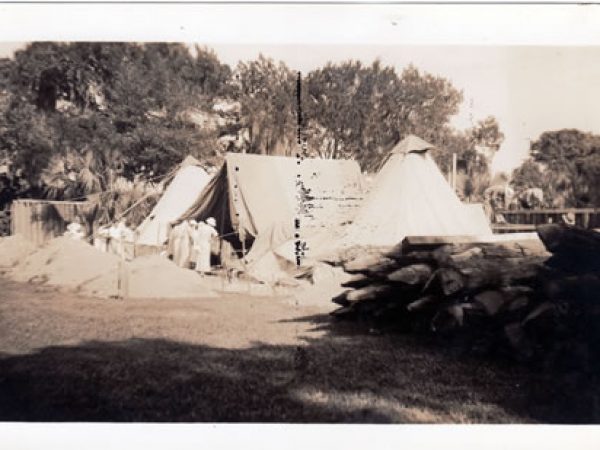

Postcard, ca. 1935, showing Christian burials at the Fountain of Youth Park Excavations underway at the Fountain of Youth Park burial ground, 1934 (Courtesy of the Fraser family and the Fountain of Youth Park, Inc.)

Excavations underway at the Fountain of Youth Park burial ground, 1934 (Courtesy of the Fraser family and the Fountain of Youth Park, Inc.)

The burials were thought to be inside a late sixteenth century or early seventeenth century Catholic church because of the tightly compacted arrangement of the graves, their highly consistent orientation and burial position, and the intrusion of some burials on earlier (Christian) burials. This pattern of Native American burial within the mission church has been well-documented in Spanish Franciscan mission sites throughout Florida (see for example).

Another group of burials was uncovered by University of Florida student Paul Hahn in 1953, located about 20 meters to the south of the group discovered in 1934. These were also Christian interments, however they were buried facing north, unlike the first group of Christian burials excavated by Dickson, which were facing east. Extensive systematic shovel tests throughout the property have failed to locate evidence for any burials between the two groups.

The presence of two early historic-period, adjacent Christian burial areas with different burial orientations is unusual. The normal practice in Catholic burial was to place burials with their feet toward the altar of the church (that is, with faces looking toward the altar). If the eastward-facing burials excavated by Dickson were, in fact, inside the church, it might indicate that the burials recorded by Hahn may have been in a cemetery outside and south of the church, buried with their feet toward the church to the north (faces looking north toward the church). Alternatively, the two groups of burials could also reflect the movement and rebuilding of the mission church in a different position during the seventeenth century.

Archaeological testing has also shown that the Timucua village associated with the early Nombre de Dios Mission was located around the church, extending in all directions. The densest early seventeenth century occupation located so far is in the southwestern portion of what is today the Fountain of Youth Park, and in the properties immediately south and west of those modern boundaries. Sub surface surveys indicated that the Nombre de Dios settlement extended southward along the waterfront, across what is today Ocean Avenue, and into the grounds of the Shrine of Nuestra Señora de La Leche. Excavations by St. Augustine’s City Archaeologist, Carl Halbirt, have also located concentrations of 17th century remains extending to the west of the Fountain of Youth Park between Magnolia St. and San Marcos Avenue.

Mural by Hollis Holbrook, ca. 1953. Exhibit Hall, Fountain of Youth Park (Courtesy of the Fraser family and the Fountain of Youth Park, Inc.)

Mural by Hollis Holbrook, ca. 1953. Exhibit Hall, Fountain of Youth Park (Courtesy of the Fraser family and the Fountain of Youth Park, Inc.) Indian council house replica erected over burial structure in 1934-35 (Courtesy of the Fraser family and the Fountain of Youth Park, Inc.)

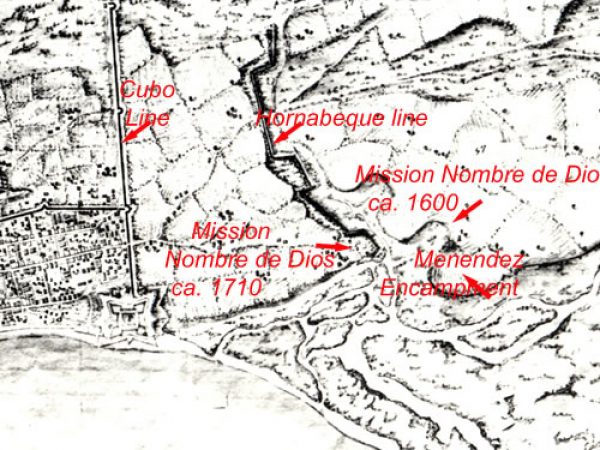

Indian council house replica erected over burial structure in 1934-35 (Courtesy of the Fraser family and the Fountain of Youth Park, Inc.) Locations of defense lines in St. Augustine ca. 1764

Locations of defense lines in St. Augustine ca. 1764

The center of the mission village moved gradually over the years toward the south, and archaeological data indicates that by the middle of the seventeenth century, the major mission village occupation was located on the grounds of what is today the Nuestra Senora de la Leche Shrine, and Catholic Mission of Nombre de Dios. This relocation possibly corresponds to a major smallpox epidemic in 1654-55, which was reported to have virtually wiped out the population of Nombre de Dios.

During the seventeenth century, probably after the epidemic, the Mission of Nombre de Dios also became the site of the Shrine of Nuestra Señora de la Leche y Buen Parto (Our Lady of the Milk and Safe Delivery), who was represented by a venerated statue from Spain. The shrine was the focus of much devotion among Catholics, and women in particular, and drew substantial offerings and alms. In 1687 St. Augustine Governor Hita y Salazar was the head of the confraternity (a lay religious organization devoted to good works) at Nombre de Dios, and he built a stone and masonry church in which to house the image.

The church was burned in 1702 by the English and Indian forces of South Carolinian Colonel James Moore, who laid unsuccessful siege to St. Augustine in that year. As a consequence, the intermediate defense line for St. Augustine (called the hornabeque line) was constructed of logs and earth, with a small bastion or lunette placed at the village of Nombre de Dios. By 1706, all of the Native Mission villages had been moved inside (south of) the Hornabeque line to provide better protection for their inhabitants. (Hann, 302) The church of La Leche was rebuilt, again of stone.

The end came for the Nombre de Dios stone church in 1728, at the hands of Col. James Palmer, another British raider who attacked St. Augustine with a force of Yamasee and English soldiers, and ravaged the church and settlement at Nombre de Dios before retreating.

After the Palmer raid, the governor of St. Augustine commanded that the Church and buildings at Nombre de Dios be dismantled.

Life at the Mission

The people who lived at the village of Nombre de Dios were in closer contact with Europeans than any other Native American group in all of Florida. The Timucuans of St. Augustine were not only the first to confront and resist Spanish arrival, but they were also the first to confront and suffer from European diseases on a continuous scale. The first decade of coexistence (1565-1575) undoubtedly reduced the Timucua population of the St. Augustine region dramatically, and this reduction was probably a major factor in the ability (and decision) of the Spaniards to relocate St. Augustine in 1572 from Anastasia Island to its present site on the mainland.

The generation of Timucuans born during the 1560’s reached adulthood in the 1580’s, which was when missionary efforts in St. Augustine realized their first successes. Success was aided by the cooperation of the Timucuan caciques (chiefs), who appear to have quickly recognized the advantages of Spanish alliance.

Doña Maria Melendez, a member of the Timucuan noble class, is an example. She was the Chieftainess (cacica) of the Timucuan town of Nombre de Dios during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Doña Maria was a Christian, and her mother (who had been the ruling Chief of Nombre de Dios before her) was one of the very early Timucua converts to Christianity. Doña Maria married a Spanish soldier named Clemente de Vernal, and he lived with her and their children at Nombre de Dios. By 1606 she had become the ruler of the Timucuan tribes extending along the coast between St. Augustine and approximately Cumberland Island, Georgia , possibly through Spanish intervention.

Detail of the ca. 1593 Mestas map of St. Augustine, showing buildings at the Nombre de Dios mission pueblo

Detail of the ca. 1593 Mestas map of St. Augustine, showing buildings at the Nombre de Dios mission pueblo Artist's rendering of Timucua Cacica Doña María Melendez, ca. 1600. Drawing by Bill Celander

Artist's rendering of Timucua Cacica Doña María Melendez, ca. 1600. Drawing by Bill Celander St. Johns pottery, the traditional ceramics of the Timucua native to St. Augustine

St. Johns pottery, the traditional ceramics of the Timucua native to St. Augustine San Marcos pottery, the traditional ceramics of the Guale people who migrated to St. Augustine

San Marcos pottery, the traditional ceramics of the Guale people who migrated to St. Augustine

Spanish mission activity also began very early among the Guale people of the coastal region of Georgia, and this provoked increasing movement of the Guale into Florida. The arrival of this new American Indian group may have had even greater impacts on life at Nombre de Dios than the Spaniards did. The Timucua people around St. Augustine, whose traditional pottery is known to archaeologists as the St. Johns series, began to use the traditional San Marcos pottery of the Guale as well as their own St. Johns pottery during the 16th century. Before the mission period, they undoubtedly acquired it through coastal trade, and small amounts of Timucua St. Johns pottery are typically found in the Guale region as well.

The gradual movement of the Guale people into St. Augustine for various reasons connected to Spanish presence and domination, however, introduced larger numbers of Guale people and larger quantities of Guale San Marcos ceramics into St. Augustine during the seventeenth century. Guale pottery was particularly favored by the Spaniards who lived in St. Augustine, who used it as their principal cooking ware, and this may have inspired local Native American potters to begin production of San Marcos pottery for sale to the Spaniards. The native Timucua inhabitants around St. Augustine, however, continued using their traditional St. Johns pottery, adopting San Marcos ceramics to in only limited amounts.

The changes and disruptions to American Indian culture in the Southeast caused by European disease, warfare, trade, evangelization and dominance are sadly reflected at Nombre de Dios. The population of the mission town not only decreased over the centuries, but became at the same time much more diversified as Christian Native Americans refugees from other regions took refuge in St. Augustine. The story is told not only in the documents and demographic figures, but also in the archaeological record of Nombre de Dios.

Christian Population of Nombre de Dios

- 1602 – 200 Timucuans (Bermejo).

- 1606 – 216 Natives, 20 Espanoles.

- 1675 – 30-35 people.

- 1689 – 20 families.

- 1711 – 39 Timucuans (16 men, 11 women, 5 boys, 7 girls).

- 1717 – 50 Timucuans (15 men, 16 women, 19 children ).

- 1726 – 62 (Chiluca) (19 men 23 women 23 children) – had stone church and convent.

- 1728 – 43 people (14 men, 17 women, 12 children).

- 1738, June – 49 (15 warriors) (Timucua 12 men, 7 women; Yamassee: 2 men eight women; Uchise 1 woman; Apalachee 2 men) (Benavides).

- 1738 (late) – 23 people.

- 1759 – consolidated; listed as Nuestra Senora de la Leche– 11 households of Timucua(6), Yamassee(23), Ibaja (10), Chiluque (1), Costa (9),Casipuya (1), Chickasaw(2).

(Sources: Hann, John 1996 The Timucua University Press of Florida, pp. 308-323;

Worth, John 1995, TImucuan chiefdoms of Spanish Florida, Volume 2. University Press of Florida. 147-155.)