Economy

The Taínos were farmers and fishers, and practiced intensive root crop cultivation in conucos, or small raised plots. Manioc was the principal crop, but potatoes, beans, peanuts, peppers and other plants were also grown. Farming was supplemented with the abundant fish and shellfish animal resources of the region. Cotton was grown and spun into cloth, and along with the many other items produced by the skilled Taíno craftspeople, was used in a widespread trade network among the islands.

Taíno socio-political organization

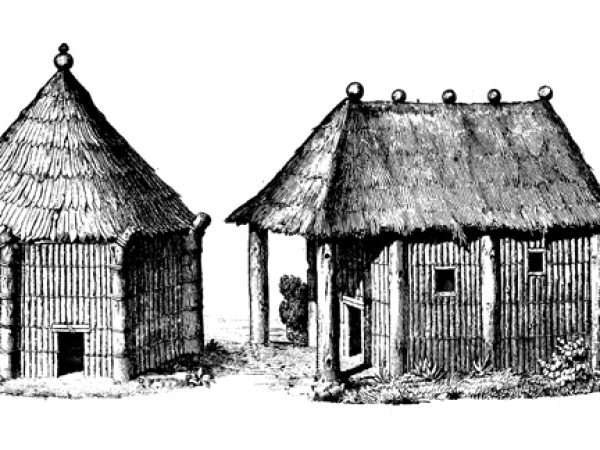

The Taíno are thought to have been matrilineal, tracing their ancestry through the female line. The Taíno of Hispaniola were politically organized at the time of contact into at least five hereditary chiefdoms called cacicazgos. Each casicazgo had a clearly recognized territory, a system of regional chiefs (caciques) and sub-chiefs, and a paramount ruler. At least two distinct social categories were recognized by the Taíno as subordinate to the caciques. According to the Spanish chronicles, the nitaínos were equated with nobles, and appear to have assisted the caciques in the organization of labor and trade. Behiques, or shamans, were part of the nitaíno group. The remainder of the population- equated by the Spaniards with commoners -were known as naborías. It is estimated that the cacicazgos each incorporated between seventy and a hundred communities, some of which had many hundreds of residents.

Taíno gender roles

Documentary accounts at the time of contact indicate that although the paramount rulers among the Taíno were most often men, women could also be caciques. Women seem to have participated at all levels in the political hierarchy, both wielding power and accumulating wealth. Pre-contact gender roles among the Taíno are not well understood, but most researchers indicated that gender roles among the Taíno were relatively non-exclusive, from political leadership and fighting as warriors to food production.

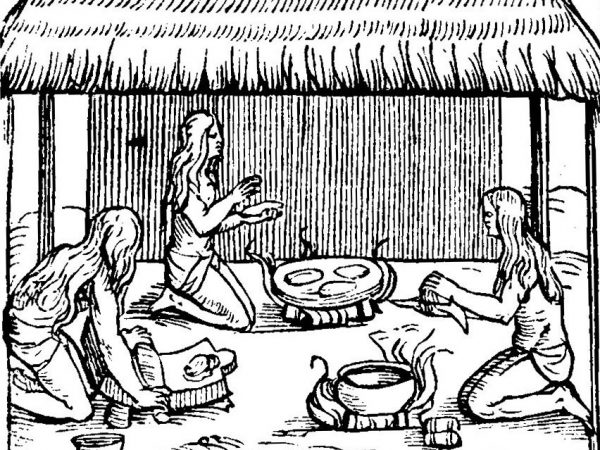

There were few social or economic activities that were assigned to only either men or only women. For example, constructing the conucos (raised mounds for farming) was done by men, and preparing the manioc was done by women, but both genders tilled, planted and harvested the fields.

Art and belief among the Taíno

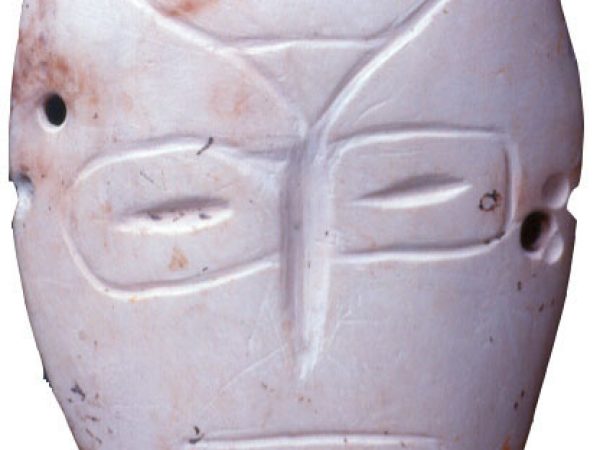

One of the most distinctive characteristics of fifteenth century Taíno society (at least to the modern observer) is the creative and exuberant artistry in material culture. Taíno artisans produced a wide variety of craft items, including elaborate decorated ceramics, cotton and cotton products, ground and polished stone beads and ornaments, carved shell and bone ornaments, tools of stone, shell and bone, baskets and hammocks, carved wooden objects, tobacco, various foodstuffs, and exotic birds and feathers.

Because the Taíno themselves did not practice writing, most of the information we have about the Taíno comes from the observations of fifteenth century Spaniards in Hispaniola. Our understanding of them is therefore undoubtedly skewed toward the Spanish point of view, and there is no doubt that the Taínos must certainly have had their own set of complex set of observations about the Spaniards.