Florida is home to nearly 700 vertebrate and more than 30,000 invertebrate animal species. At the same time, 21.3 million people take up residence and 100 million tourists visit the state each year, making human-animal interaction inevitable.

Sometimes, these interactions make headlines. Here are six Florida animals who have made the news this month.

1. Shorebirds

Nesting season for Florida’s shorebirds, which include gulls, herons, egrets and terns, is currently underway around the state. These seasons range from mid-February to September, depending on the region.

Because of increased coastal development and habitat loss, bird populations are largely restricted to stretches of beach within parks and preserves. Since environmental conditions on Florida’s beaches are already unpredictable, shorebirds are particularly sensitive to human disturbance. At Gulf Islands National Seashore, increased speed enforcement is currently underway minimize the number of shorebirds killed by vehicle traffic as they cross the road.

Wildlife officials say we can all do our part to ensure the survival of Florida’s waterbirds.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has some tips for living in harmony with beach-nesting birds:

- Never enter areas posted with shorebird/seabird signs.

- Avoid driving on or beyond the upper beach.

- Drive slow enough to avoid running over chicks.

- Keep dogs on a leash and away from areas where birds may be nesting.

- Keep cats indoors, and do not feed stray cats.

- Properly dispose of trash to keep predators away.

- Do not fly kites near areas where birds may be nesting.

- When birds are aggravated, you are too close.

To find out when nesting season is in your region, visit: Shorebird Breeding Seasons and Regional Contacts

2. Oysters

Apalachicola Bay once supported a booming oyster industry, producing most of the state’s oysters. According to the FWC, businesses in the Franklin County area sold more than 3 million pounds of oysters in 2012.

But a series of natural and man-made disasters, such as the 2010 Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill, pushed the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to declare the region as a fishery disaster in 2013. The declaration was a huge blow to the Franklin County community, home to generations of oystermen.

Florida State University’s Coastal and Marine Laboratory has received $8 million to study how to revive Apalachicola Bay. The 10-year project is funded by Triumph Gulf Coast, a nonprofit established by the state legislature to manage the disbursement of $2 billion received by the state from the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill settlement.

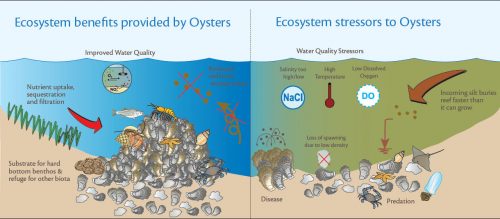

Sandra Brooke, scientific director for the lab, said when oysters go away, the ecosystem changes. For one, oysters serve as vacuum cleaners. It is estimated that one oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water per day.

“So, we first need to understand what is going on in the bay, and then we can move forward with developing a restoration plan,” Brooke told FSU news.

This isn’t the first time university researchers have been called to study the bay. In 2016, the University of Florida received a $4.19 million grant to study how to conduct reshelling efforts in Apalachicola Bay. The five-year project is currently underway. Project updates can be found at: UF/IFAS Oyster Recovery

At the same time, Franklin county officials are supporting the county’s growing interest in oyster aquaculture leases to support locals displaced by the industry collapse.

Manatees

Three Florida lawmakers have filed budget appropriation requests for $400,000 to help the South Florida Museum (home of the late Snooty) provide better rehabilitation to sick and injured manatees in the state. The money would be used to purchase a new mammal rescue vehicle, a new ceiling in the Museum’s Parker Aquarium and a generator to power the tank in case of a power outage.

Florida is home to five manatee critical care facilities, including Zoo Tampa at Lowry Park and SeaWorld Orlando, that provide life–saving services for manatees. Secondary facilities, like the South Florida Museum provide a short-term living situation after the animals are stabilized and before they are released to the wild.

Last year was a particularly rough one for manatees. A 15-month long red tide emitted neurotoxins that attacked the nervous systems of hundreds of manatees. On and off blue-green algae blooms in the Indian River Lagoon suffocated seagrasses, making it hard for manatees to eat the 150 pounds they need each day. Additionally, ZooTampa was out of service as a manatee rehabilitation critical care facility for some time, which limited the number of manatees the state could take.

“There’s always a need to rehab manatees,” South Florida Museum CEO Brynne Besio told the Miami Herald. “That’s why the bill is there, so that we’ll keep going with modernization and what’s best for the animals.”

To learn more about how you can help protect Florida manatees, visit: How Can I Help Florida Manatees?

Sharks

Stephen Kajiura, a researcher at Florida Atlantic University, has been studying the annual migration of blacktip sharks as they make their way south to warmer waters along Florida’s Atlantic coast.

“We welcome blacktip sharks back to South Florida because they are critically important to our ecosystem. They sweep through the waters and ‘spring clean’ as they weed out weak and sick fish, helping to preserve coral reefs and sea grasses,” Kajiura told FAU news.

To collect the migration data, Kajiura attaches a reusable radio and satellite sensor to the shark’s dorsal fin for two to four days. The data collected will give insight into how the shark population responds to warmer ocean temperatures as a result of climate change.

“For years, we have gathered and documented data about their migration patterns with photos and videos that we captured by aircraft, boat and drones. This latest instrument is providing us with a very different perspective on how these mysterious animals behave.”

Learn more at: They’re Back! Scientists Now Have Intimate Shark Diaries

Bonefish

Bonefish are an important sport fish in South Florida, contributing to a flats fishery with an annual economic impact of more than $465 million. But, scientists with Florida International University say that bonefish populations are also an important indicator of the state’s environmental health.

FIU coastal ecologist Jennifer Rehage and her team found that although bonefish live in salty marine environments, their juveniles are spending time in lower salinity, or brackish, waters such as Florida Bay. Situated between the southern end of the Florida peninsula and the Florida Keys, the bay is “sensitive to changes in the quality, movement and distribution of water in the Everglades,” reads an FIU news post.

“People haven’t looked for bonefish in low-salinity environments because they think they’re a marine species,” Rehage told FIU news. “This finding tells us the link between bonefish, freshwater and the Everglades is stronger than we previously thought. We need to consider low-salinity habitats in bonefish conservation and management.”

Read the full article here: It’s Time to Ratchet Up Bonefish Restoration, Scientists Say

Shoal Bass

Shoal bass are native to only one river basin in the world —the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin — and habitat loss from dams and reservoirs and sediment runoff into waterways is decreasing the fish’s range.

“In the Chipola River, the population is stable but its range is limited. Some of the most robust shoal bass numbers are found in a 6.5-mile section between the Peacock Bridge and Johnny Boy boat ramp,” writes Andrea Albertin, UF/IFAS Extension agent on UF/IFAS Blogs. “The FWC has turned this section into a Shoal Bass catch–and–release only zone to protect the population. However, impacts from agricultural production and ranching, like erosion and nutrient runoff can degrade the habitat needed for the shoal bass to spawn.”

Albertin explains that protection of the shoal bass can help protect other species, and the ecosystem as a whole. This is because the shoal bass is an apex predator, meaning it is at the top of its local food chain. Apex predators help keep prey numbers in check.

Farmers along the Florida’s Chipola River have teamed with the Southeastern Aquatic Resources Partnership to help protect shoal bass habitat by improving farming operations and implementing agricultural best management practices that conserve water and reduce sediment and nutrient runoff.

For more information about BMPs and cost-share opportunities available for farmers and ranchers, contact your local FDACS field technician: https://www.freshfromflorida.com/Divisions-Offices/Agricultural-Water-Policy/Organization-Staff

For questions regarding the Native Black Bass Initiative or Shoal Bass habitat conservation, contact Vance Crain at vance@southeastaquatics.net