2018-2020 UF Thompson Earth Systems Institute Faculty Fellow

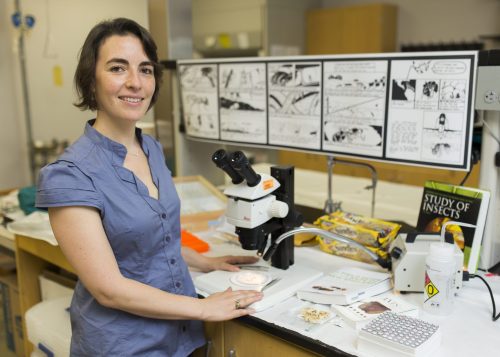

Assistant Professor of entomology

UF/IFAS College of Agriculture & Life Sciences

Phone: 352-273-3952

Email: alucky@ufl.edu

Every kid goes through a bug phase. Andrea Lucky, a faculty fellow with the University of Florida Thompson Earth Systems Institute, never grew out of hers.

Every kid goes through a bug phase. Andrea Lucky, a faculty fellow with the University of Florida Thompson Earth Systems Institute, never grew out of hers.

Although Lucky has an appreciation for most insects, she has to admit there’s just something about ants that drove her to study them. Perhaps it’s their success globally. There are more than 20,000 different species of ants on the planet. Or their complex and organized societies. An ant colony is able to achieve far more than the individual workers are capable of. Or their strength. A single ant can carry up to 50 times its own body weight.

But to Lucky, one of the most special characteristics about ants is their accessibility.

“People always have ant stories,” Lucky said. “All you have to do to study them is look down. To me that’s one of the most exciting things —that kind of connection when I’m interacting with people. ”

For these reasons, Lucky, who is an assistant professor of insect systematics with the UF Institute for Food and Agricultural Sciences, decided to use ants as a basis for collaborating with public audiences to study how invasive species are changing Earth’s ecosystems.

“We know that ants have huge impacts on ecosystems,” Lucky said. “They are keystone species and predators. They also have very specialized relationships with plants and other organisms. What we don’t fully understand is the effect of exotic ants on Florida’s ecosystems.”

For this reason, ants have the ability to signal small, but significant changes in our ecosystems.

In 2011, while Lucky was a postdoctoral researcher at North Carolina State University, she and her colleague Rob Dunn, a professor of applied ecology at NCSU, launched an online citizen science project, School of Ants.

The program calls upon curious citizen scientists around the nation to help her answer several questions.

Where are exotic species distributed?

How do introduced ant species change local ecosystems?

What happens to native ants as a result of habitat loss and invasive species?

To help collect data, program participants first create a collection kit made from household items. Using cookies as bait, they make note of how many ants come to feast. They record their data online and send their samples to Lucky’s lab for analysis.

Once the ants are identified, the data goes into an online interactive map so participants can see what ants have been found in their cities. So far, Lucky’s lab has received thousands of samples.

“The response has been huge. People have really loved participating,” Lucky said. “Participants start focusing on things they might not notice otherwise. Cool behaviors, these dynamics and different species. It really does get people to pay attention locally.”

Lucky’s main goal with the School of Ants project is to give people context into how invasive species have altered our local environments.

“If people collect 10 species of ant in their yard and seven of them are exotic species —that actually brings the message home pretty well,” she said.

Lucky said this project taught her important lessons about science communication.

“You don’t need to teach people things,” she said. “It’s better to show them context and then ask them to participate in ways that are meaningful to them.”

She hopes to bring this insight to help TESI launch similar projects that get people involved with Earth Systems science.

“A major goal of my work is to make science accessible and available to the general public, particularly to make the process of doing science accessible to non-scientists,” Lucky said. “I am excited to be collaborating with the TESI team to achieve this goal.”