One of Florida’s most valuable resources is its water. The state is rich in freshwater springs and aquifers that flow through its limestone bed; thousands of lakes and rivers; extensive natural filtration systems in the form

of wetlands, marshes, and estuaries; and an endless coastline bordering both the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. But the natural flow, nutrient content, and clarity of these waters are at odds with one of the fastest growing populations in the nation, and the extensive development, urbanization, and waste that come along with it.

Many of this session’s bills relate to the oversight of wastewater treatment plants and onsite sewage treatment and disposal systems (OSTDs), also known as septic systems. Septic systems are an especially potent issue, as 30% of the state’s residents rely on these underground tanks to dispose of their wastewater. Systems that are poorly installed or maintained can leach contaminants and excess nutrients into the groundwater. To keep them operational, tanks should be pumped every 3 to 5 years. But of the 2.6 million septic tanks in Florida, only about 100,000 are pumped each year, leaving behind hundreds of thousands of outdated, leaky systems. Combined with poor, sandy soils and shallow water tables, these systems are often sources of pollution in Florida’s waterways and coastal regions.

A couple of the bills this session also seek to address the climate-related water issues that coastal communities are facing, including rising sea levels, saltwater intrusion, and red tide.

Here is some of the water-centric proposed legislation this year:

- Safe Waterways Act

- Land and Water Management

- Management and Storage of Surface Waters

- Advanced Wastewater Treatment

- Local Government Coastal Protections

- Florida Red Tide Mitigation and Technology Development Initiative

- Department of Environmental Protection

- Statewide Drinking Water Standards & Preventing Contaminant Discharge

- Other Related Bills

Sampling of Beach Waters and Public Bathing Spaces

Florida saw a record-breaking 137.4 million tourists in 2022, many of whom are drawn to the 825 miles of sandy coastline and year-round warm weather. Locals also take advantage of the state’s natural areas, with 75% of the population participating in outdoor recreation in 2016.

However many water bodies in Florida, including beaches, lakes, and rivers, have been routinely found to be contaminated with bacteria that can induce gastrointestinal illnesses, including diarrhea and vomiting. A 2022 report identified 943 miles of streams, rivers, and springs and 1,741 acres of lakes and reservoirs that were impaired with fecal coliform, E. coli, or Enterococci and overlapped with source waters for community water systems.

Beach closures have also been commonplace, including a no-swim advisory in Miami posted in early 2023 after 2,800 gallons of wastewater emptied into Biscayne Bay.

Bacteria can get into Florida’s waterways a number of different ways. Stormwater runoff, sewage overflows, leaking septic tanks, and manure and fertilizer runoff can all contaminate groundwater and surface waterways.

Florida State Sen. Lori Berman (D) and Florida State Reps. Peggy Gossett-Seidman (R) and Lindsay Cross (D) introduced identical SB 338 and HB 165, respectively, which would require the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to adopt health standards and prescribe procedures and timeframes for a bacteriological sampling of beach waters and public bathing places.

Section 514.011 of the Florida Statutes describes a “public bathing place” as “a body of water, natural or modified by humans, for swimming, diving, and recreational bathing used by consent of the owner or owners and held out to the public by any person or public body” and may include “lakes, ponds, rivers, streams, artificial impoundments, and waters along the coastal and intracoastal beaches and shores of the state.”

The proposed legislation, which was unsuccessful in both 2022 and 2023, requires:

- The Department of Health (DOH) to submit a report detailing the department’s bacteriological sampling of beach waters and public bathing places.

- The transferring of all duties relating to the bacteriological sampling from the DOH to the DEP by July 1, 2025.

- Owners of beach waters and public bathing places to notify the DEP and resample the water within 24 hours of a result indicating substandard water quality.

- The DEP to close beach waters and public bathing places that do not meet standards.

- Municipalities and counties to notify the DEP in case of any incident that might impair their beach waters or public bathing places.

- The DEP to investigate wastewater treatment facilities and outfall pipes near affected waters.

- The DEP to post a sign with specific, clear language in case a health advisory is issued for a body of water. The sign must be displayed prominently, such as at beach access points.

“The public has a right to know whether the beaches and waterways they’re swimming in are infested with fecal bacteria, (and) Florida is failing in its responsibility to promptly inform the public and protect their health,” Berman told Florida Politics. “All we’re asking for is transparency in water quality and consistency in public notification so residents and tourists can safely enjoy our world-famous waters.”

UPDATE: SB 338 died – however, its companion bill HB 165 was enrolled, meaning it was approved by both the House and Senate and sent to Governor DeSantis for approval.

Land and Water Management

Florida’s wetlands, lakes, and ponds are essential to the fabric of ecological stability. Wetlands in particular are mechanisms of filtration, flood control, carbon sequestration, and habitat formation.

“Wetlands are really integral to the sustaining of Florida’s biodiversity—one-third of endangered species in Florida use small ponds for some part of their lifecycle,” said Matt Cohen, director of the UF Water Institute.

Florida State Sen. Danny Burgess (R) and Florida State Rep. Randy Maggard (R) introduced two similar bills SB 664 and HB 527, respectively, after a duo of bills of the same name died during last year’s session.

The legislation would preempt the regulation of dredge and fill activities to the state, meaning counties and municipalities would no longer be allowed to place controls on projects that could alter or degrade wetlands and other surface waters.

The bills would also create requirements relating to buffer zones, which are areas of vegetation bordering a body of water to reduce pollution runoff, control flooding, and provide habitat for wildlife.

As Cohen said, the pond itself isn’t the whole picture. “The organisms are using the wetland and the adjacent habitat: if you want to protect the function of a wetland, you have to protect the adjacent habitat as well.”

The bills state that any buffer zone established by a city or municipality exceeding the baseline set by the DEP must be purchased by that city or municipality. This would affect local governments that have created buffer zones that are larger than the state minimum.

“Alachua [County] imposes a buffer of 75 feet around a wetland where development is not allowed, [but] the statewide buffer is only 35 feet,” said Cohen.

He believes that preemption clauses like the one in SB 664 are directed towards places like Alachua County that provide protections that are above and beyond what the state provides.

“You as a community can’t do more. You can’t protect wetlands more, you can’t supersede state law, because the legislature has prioritized property rights. It pulls the rug out from under the communities,” he said.

The bills would also repeal Section 373:591 of the Florida Statutes, which facilitates the formation of management review teams to ensure conservation, preservation, and recreation lands are being managed properly.

UPDATE: SB 664 died in the Environment and Natural Resources Committee; HB 527 died in the Water Quality, Supply & Treatment Subcommittee.

Management and Storage of Surface Waters

SB 986 and HB 863, similar bills proposed by Florida State Sen. Colleen Burton (R) and Rep. Sam Killebrew (R), respectively, aim to lessen oversight on some governmental projects. Practices that are primarily for environmental restoration or water quality improvement on agricultural or government-owned lands would be exempt from certain regulations and permits. Similar bills were introduced in the 2023 session but died in committee.

Authorized practices may alter the topography of the land, divert or impede water flow, and impact wetlands as long as the final outcome is deemed as a “net increase in wetland resource functions.” The bill also omits an existing section of the Florida Statutes, which states that allowed practices must have minimal or insignificant individual negative impacts on the water resources of the state.

However, the bill text does not specify what these practices would include or what projects they would apply to, leaving the implications of the bill somewhat in question.

The problem, Cohen said, is in the interpretation of such practices.

“Who gets to constitute a benefit, and who gives oversight?”

This exemption would not apply to the establishment of mitigation banks, where environmental improvement projects are undertaken so the site can be sold as credits to offset other, potentially damaging projects.

UPDATE: SB 986 died in the Environmental and Natural Resources Committee; HB 863 was withdrawn prior to introduction.

Advanced Wastewater Treatment

In Florida, waterbodies are considered impaired by the DEP, and added to the “303 (d) list,” when they do not conform to the water quality standards set by the Clean Water Act and federal regulations.

Impairment can result from a combination of factors. Ashley Smyth, a University of Florida assistant professor in biogeochemistry researching the transport of nutrients in coastal ecosystems, described how sewage disposal facilities can contribute to impairment status.

“There are point-sources and non-point sources of pollution. [Non-point] is runoff that captures everything across the landscape where you can’t pinpoint the source. A point-source is a pipe, or something that you can point to. A wastewater treatment plant is a common point-source,” Smyth said.

SB 1304, proposed by Florida State Sen. Lori Berman (D), and HB 1153, proposed by Florida State Reps. Lindsay Cross (D) and Jim Mooney (R), aim to target wastewater plants that are, or could become, these point sources of pollution.

The bill would require the DEP to submit reports detailing the operations of sewage disposal facilities with capacities greater than 1 million gallons per day, including information on the level of treatment and the impairment status of neighboring water bodies.

It would also require the DEP to submit a priority ranking process to upgrade all facilities in Florida to advanced wastewater treatment by 2035 using environmental benefit parameters, including deaths of fish and wildlife, surrounding water quality, and public health advisories. Progress reports would also be required for any improvement projects pursued at high-capacity facilities.

UPDATE: SB 1304 died in the Environment and Natural Resources Committee; HB 1153 died in the Water Quality, Supply and Treatment Subcommittee.

Local Government Coastal Protections

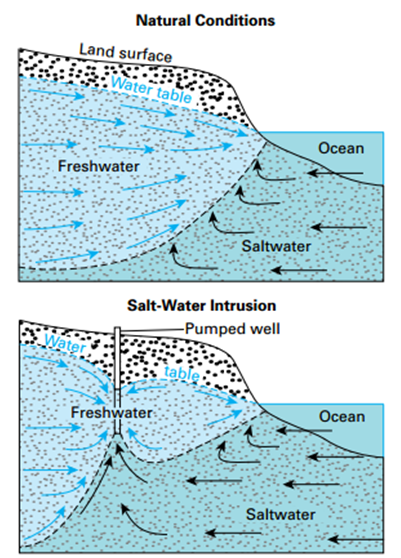

The rate of sea level rise around Florida is accelerating, putting low-lying communities in South Florida and on the coast at risk of greater storm surge, flooding, saltwater intrusion, and groundwater contamination.

The Resilient Florida Program currently offers grants to counties, municipalities, water management districts, and flood control districts to conduct resiliency assessments and address the risk of inland and coastal flooding and sea level rise.

SB 298 and the similar HB 1079, proposed by Florida State Sen. Tina Polsky (D) and Rep. Fiona McFarland (R), respectively, seek to expand the program to include funding for coastal counties conducting saltwater intrusion vulnerability assessments.

Saltwater intrusion occurs when sea level rise and excessive groundwater pumping allow seawater to flow into lower elevation, fresh groundwater sources. By increasing the salinity and level of groundwater, intrusion effectively reduces the amount of drinkable water, increases flood risk, and hinders the growth of crops.

Smyth said that it can even lead to excess nutrients in the water supply.

“Results from our study showed that when you get [saltwater intrusion], it will release nutrients in the soil and make them available, which can actually contribute to nutrients affecting water quality downstream.”

Expansion of the program will require grant recipients to analyze their coastal county’s primary water utilities and project how current wellfields may be impacted by saltwater intrusion over the next decade, and the costs associated with relocating compromised wells. The bill will also require the DEP to update its Comprehensive Statewide Flood Vulnerability and Sea Level Rise Data Set based on the vulnerability assessments and make the results publicly available.

UPDATE: SB 298 died in Messages: HB 1079 died in the Agriculture, and Natural Resources Appropriations Subcommittee.

Florida Red Tide Mitigation and Technology Development Initiative

Red tide in Florida most often refers to large blooms of the algae Karenia brevis (K. brevis) that can occur during late summer and early fall. Increasing sea surface temperatures caused by climate change have likely intensified the naturally occurring blooms. Wave action can release brevetoxins, a kind of neurotoxin, from the algae and lead to sickness or even death for fish and other marine animals. Coastal communities can also be affected when wind propels the toxins inland, causing respiratory irritation for some people.

SB 1360, proposed by Florida State Sen. Joe Gruters (R), and the similar HB 1565, proposed by Florida State Rep. Michael Grant (R), build upon 2019 SB 1552, which established the Florida Red Tide Mitigation and Technology Development Initiative as a partnership between Mote Marine Laboratory (Mote) and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC).

The Initiative is an ongoing effort to collaborate with scientists and develop novel technologies to predict red tide events and mitigate their effects.

The proposed legislation seeks to extend the expiration date of the Initiative from June 30, 2025, to June 30, 2027. It will also direct the development of field trials and require a report of the technology to be submitted to the DEP for approval. If the DEP does not assess and approve, or deny, the technology within 30 days, it will be considered approved.

UPDATE: SB 1360 was laid on the table, meaning it was set aside and died at the end of the session – however, its companion bill HB 1565 was enrolled and sent to Governor DeSantis for approval.

Department of Environmental Protection

SB 1386, proposed by Florida State Sen. Alexis Calatayud (R), and HB 1557, proposed by Florida State Rep. Linda Chaney (R) make revisions on several topics relating to water quality regulation.

The bills would allow a representative of the DEP to, at any time, enter properties that are not exclusively private residencies to inspect OSTDs, or septic systems, and ensure they are up to code.

The bills would direct the DEP and water management districts to allow extended permits for water resource development proposals that use reclaimed water.

They would also expand the scope of the Statewide Flooding and Sea Level Rise Resilience Plan, which creates a priority list of projects in coastal and inland communities that address flooding, storm surge, and sea level rise. Similarly, the Comprehensive Statewide Flood Vulnerability and Sea Level Rise Data Set would be required to include the 20- and 50- year sea level rise projections based on data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The Nature Coast Aquatic Preserve is the second-largest aquatic preserve in Florida, covering 800 square miles of coastal waters that are home to extensive seagrass meadows, oyster reefs, mangrove islands, marshes, and marine springs. The proposed bills would increase penalties for scarring any of the 400,000 acres of seagrass in the preserve, which provide shelter for countless organisms, filter water, and support seafood production.

The bills would also establish the Kristin Jacobs Coral Reef Ecosystem Conservation area as an aquatic preserve, increasing protections for a section of the only barrier reef system in the continental United States.

UPDATE: SB 1386 was laid on the table, meaning it was set aside and died at the end of the session – however, its companion bill HB 1557 was enrolled and sent to Governor DeSantis for approval.

Statewide Drinking Water Standards & Preventing Contaminant Discharge

1,4-dioxane is reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services but is not regulated at the federal or state level. The human-made chemical exists in products such as paints, cosmetics, detergents, food packaging, and pesticides and can contaminate the air, groundwater, and soil. Exposure to 1,4-dioxane, whether through drinking, breathing, eating, or skin contact, can cause health issues as serious as liver and kidney damage or death. It has been found in drinking water in northwest Seminole County, Lake Mary, and Sanford, Florida, sometimes exceeding the recommended health limits.

SB 1546 and the identical HB 1533, proposed by Florida Sen. Linda Stewart (D) and Florida State Rep. Rachel Saunders Plakon (R) respectively, aim to turn what are currently recommendations into enforceable rules regarding 1,4-dioxane limits in drinking water. The bills would require the DEP to establish a statewide drinking water maximum contaminant level of less than or equal to 0.35 micrograms per liter for 1,4-dioxane.

The legislation would also require public water systems to test their groundwater wells within the year to ensure compliance with the limit. If 1,4-dioxane levels exceed the maximum, the public water system would need to submit a mitigation plan and conduct retests. Test and retest results must also be made publicly available to ensure transparency.

A similar set of proposed bills, SB 1692 by Florida State Sen. Jason Brodeur (R) and HB 1665 by Florida State Rep. Peggy Gossett-Seidman (R), are trying to target the source of 1,4-dioxane and other harmful chemicals, known as Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). PFAS are found in many of the same household, personal care, and food packaging products as 1,4-dioxane, and also have adverse health effects on people. But PFAS are also characterized as “forever chemicals,” meaning they may be more resistant to degradation than 1,4-dioxane is.

These two bills would establish the PFAS and 1,4-Dioxane Pretreatment Initiative with the DEP to detect and remove the chemicals at the source before they contaminate drinking water. They would require collaboration between the DEP and wastewater facilities to identify industrial users that are probable point sources of the pollution. Industrial facilities would also be required to comply with pretreatment standards to prevent further contamination.

UPDATE: SB 1546 died in the Appropriations Committee on Agriculture, Environment, and General Government; HB 1533 died in the Water Quality, Supply and Treatment Subcommittee. SB 1692 died in the Fiscal Policy Committee; HB 1665 died in the Water Quality, Supply and Treatment Subcommittee.

Other Related Bills:

- Ratification of the Department of Environmental Protection’s Rules Relating to Stormwater – SB 7040 and HB 7053 (HB 7053 was laid on the table and died at the end of the session – however, its companion bill SB 7040 was enrolled and sent to Governor DeSantis for approval.)

- Mitigation – SB 1532 and HB 1073 (HB 1073 was laid on the table and died at the end of the session – however, its companion bill SB 1532 was enrolled and sent to Governor DeSantis for approval.)

- Excise Tax on Water Extracted for Commercial or Industrial Use – SB 510 (died in the Environment and Natural Resources Committee)

- Regulation of Water Resources and Water Well Contractors – SB 1136 and HB 1163 (HB 1163 was laid on the table and died at the end of the session – however, its companion bill SB 1136 was renamed, enrolled, and sent to Governor DeSantis for approval.)