Part of every experiment is the collection of data. As a field biologist, that means I have to go where my study animals are. In this case, that was New Smyrna Beach (NSB), Florida, also known as the shark bite capital of the world. We hoped to tag blacktip sharks (Carcharhinus limbatus) and monitor their daily movements in connection with environmental patterns to determine when sharks and beachgoers are most likely to overlap. This information could be used in creating better beach safety protocols, like warnings on days with predicted increases in sharks in the area. After over a year in lockdowns, we were all going a little stir crazy. Vaccines had just rolled out, and as you might have read in a previous blog, I had a week in Cedar Key to test out our new equipment and techniques. Now it was time for the real deal: a month-long field season. Joining me, again, was my loving and patient partner and our cat. Before you ask: due to the limited size of our boat, Lo did not join us on the water. We arrived in town the day before Memorial Day. Little did we know this is actually the busiest day of the year at NSB. The streets were

packed with cars and sidewalks even busier with tourists. Palm trees lined the streets, and chickens darted among the many pedestrians, giving the area the feel of a tropical Caribbean Island. Over the course of an hour, we crawled half a mile along a two-lane road to the Coast Guard station. We were fortunate enough to have been allowed to leave our boat there during the month. Unfortunately, the turn-off for the station was also beach access, and if the line of cars was any indication, the beach was packed. Deciding that the water would be too crowded for the holiday weekend, we decided to get to know the local area by visiting all of the bait and tackle shops. We introduced ourselves to the shop owners, told them what we were doing, and asked if we could post signs for an ongoing creel survey. A creel survey is an estimation of population sizes based on catch rates of recreational anglers. Citizen science is a huge tool for biologists, and we were eager to start engaging the locals here at NSB.

After the festivities of the holiday had died down, we finally made it out to the Coast Guard station at dawn. However, when we arrived, the gate was locked, and no one was picking up the phone. After finally getting ahold of a sleepy-eyed petty officer, we found out that the gate would remain locked until 6 o’clock. This was all my partner needed to hear to justify a trip to the fancy local coffee shop down the road. When we got back to the Coast Guard station, we talked to several folks who informed us that the road was being repaved, but they didn’t know the schedule due to thunderstorms. This would mean that we would have to move our boat’s parking spot around for the next several days. Sort of like musical chairs, only you’re just a tiny skiff, and giant military boats are your competition. As anyone from Florida knows, summer thunderstorms roll in without warning. We spent more than half of our month running in and out of the water to get away from storms, as our boat was open to the elements.

We finally made it out onto the water of Ponce de Leon inlet. The inlet is wide, but a thin deep center channel is the only area accessible for most boats. The strong undercurrent moves sandbars around constantly, so veering from the channel means risking running aground. The whipped-up sediments give the water a greenish chocolate milk color, so you feel the sandbars before you see them. Between the boat traffic and strong current, the inlet’s surface water is always moving. You feel each little wave as you bounce and roll.

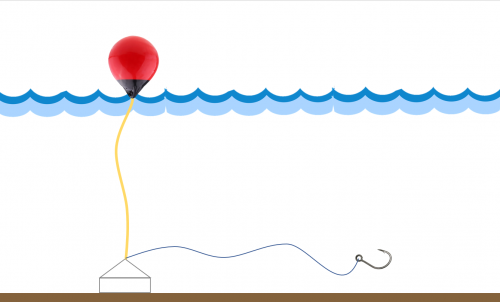

Despite the holiday weekend having already passed, boat traffic was still extremely high. We cast out our lines, and while they soaked, we explored the area and all of the small cuts through mangrove patches. We were using drum lines to fish. These have a 40lb+ weight that a line with a hook is attached. The shark grabs the hook, but the weight is too heavy for the animal to get away. There is also a separate line with a float so we can find the drum again. Because the main channel was the only deep water, most of the habitat was too shallow for us to properly set our lines. We would have to stay near the main channel and humans in their boats.

I had noticed that the quality of bait we had bought wasn’t great and had appeared to have been frozen and thawed several times. This meant it was hard for the soft meat to stay on the hooks. As I didn’t have a good local source yet, I took to fishing forums for a solution. That’s when I discovered the bait twine technique that the British often use when catfishing to bind up mushy meat, keeping it on the hook. On the 4th of June, with the bait now firmly secured to the hook, we finally caught our first shark! A 5-foot female spinner shark (Carcharhinus brevipinna) took the bait on one of our drum lines near the mouth of the inlet. It took us a moment to gather our synergy, but we safely released our first catch of the trip. Within the next hour, we had our second shark. Deeper into the mangroves, we had set a drum line. However, our gear was not intended to hold up to the large bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) that ended up destroying the line and chewing its way free. Unfortunately, these sharks were not our target species, and we lacked the permits to tag them.

For this study, we were using acoustic tags. A transmitter would be surgically implanted in a shark’s belly and would give off a signal every couple of seconds. To record these signals, we need an array of receivers. These stationary devices record the time that nearby tags are picked up. Our receivers were housed in a special float to protect them from any bottom trawls and secured to the bottom with large sand agar. Another research team had three acoustic receivers in the area but hadn’t checked on them in many years. They offered for us to use them and gave us the GPS coordinates. One of the admin beach safety officers offered to take us out on his day off using his personal boat. Were slowly floated the inlet on the sunny day until we came to the receiver’s location on a sign mounted in the water. That day, we could only locate that single receiver but managed to download the old data and replace the batteries. That receiver had logged 14 tagged animals in the area 806 times over a two-year period. Everything from fish to manatees. The rough swells from yet another afternoon thunderstorm made locating the other two impossible. The current where the other receivers were located was extremely strong at the bottom. So, this would be a team effort, and we needed more divers in the water. Having seen all the data these old receivers had gathered, my excitement for our study was growing by the second.

After several days of not finding our species of interest and being chased from the field by storms, our Airbnb was supposed to be a place of rest. However, walking into the kitchen one evening and seeing a significant amount of water did begin to damage my calm. I would soon find out that the washing machine had a disconnected water line. Not knowing where the shutoff valve was made for several interesting minutes, followed by some light mopping. I had thought this would be the worst episode with the house, but I hadn’t found the termites yet.