A follow up to yesterday’s post.

As mentioned yesterday, large bones and fragments are easy (relatively) to find in the field. Collections include turtle shell, ungulate jaws, rhinoceros and even crocodillian skulls. Hidden within the same layers we find these bones, however, are even more fossils. These fossils, which include teeth and bone fragments of rodents, bats, and other small vertebrates, are often the size of the sediment grains in which we dig, if not smaller.

In order to find these micro-specimens, we must separate bone from sediment.

We separate trash from treasure in a process known as wet sieving, or screenwashing. Sediments are soaked thoroughly and run through a series of wooden boxes with mesh screen bottoms of increasingly smaller sizes. Running the samples through these sieves allows dirt and smaller grains of rock to fall through the screens, leaving behind larger fragments.

Not every location in which fossils are found is necessarily a good location for screenwashing. Sites comprised of well consolidated rock can hardly be used – instead a site is needed that consists of soft sedimentary rocks such as mudstone, claystone, and siltstone. These can easily be broken down and washed.

Following the washing, sediments are lain down to dry.

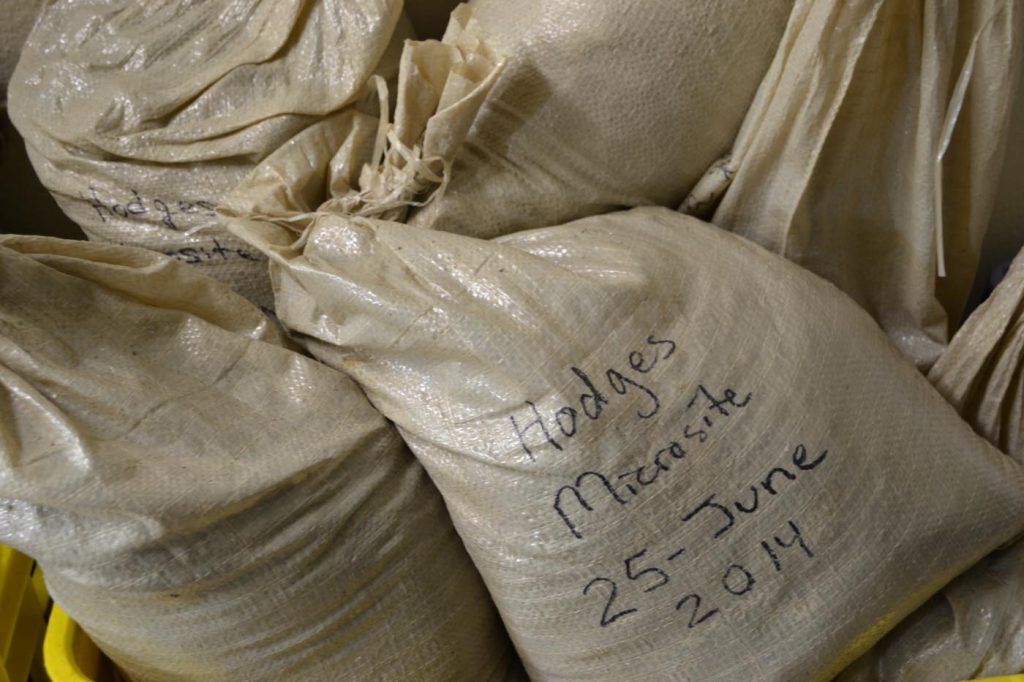

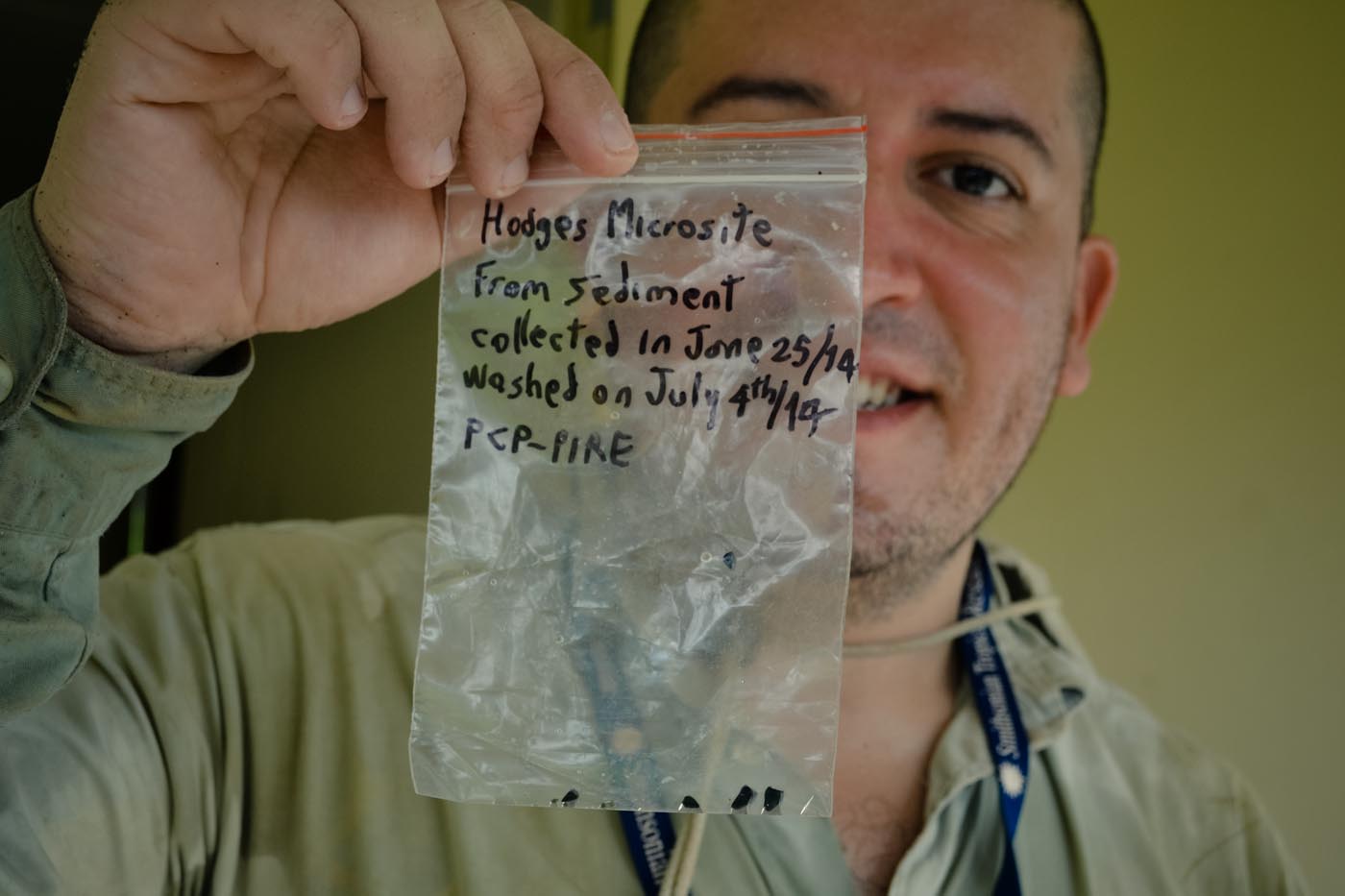

Once dry, sediments are bagged and labeled so they can be sent for further sorting and inspection under a microscope.