Defining taxon: first appearance of 17 mammalian genera dispersing more or less simultaneously from Eurasia (Tedford et al., 2004); among those found in Florida are the bear-dog Amphicyon, the hemicyonine bear Phoberocyon, the mustelid Leptarctus, the rhino Floridaceras, and the dromomerycid Aletomeryx

Basis of name: Wood et al. (1941) based the name on the Hemingford Group, a stratigraphic unit from western Nebraska that was named for the town of Hemingford in Box Butte County. The stratigraphy of the early Miocene rocks of this region of Nebraska and adjoining parts of Wyoming have a long, complex history (McKenna, 1965; Hunt, 2002). The primary fossil mammals and faunas originally assigned to the Hemingfordian NALMA from western Nebraska by Wood et al. (1941) are now considered to be derived from the Runningwater and Sheep Creek formations, which are placed in the Ogallala Group (Tedford et al., 1987; 2004).

Hemingfordian faunas are less common than those from the Barstovian, but are widely scattered through the central and western US. The two areas of greatest concentration are southern California and western Nebraska/eastern Wyoming/eastern Colorado/southern South Dakota. The Garvin Gully Fauna is an assemblage of many small sites located in coastal Texas. In the eastern US, there are about 30 Hemingfordian fossil localities in Florida and one in Delaware. There are also several Hemingfordian localities in Mexico (Montellano-Ballesteros and Jiménez-Hildalgo, 2006) and exposures along the Panama Canal have produced the early Hemingfordian Centenario Fauna (MacFadden et al., 2014).

The Hemingfordian is divided into two subintervals: the He1 from 18.9 to 17.5 million years ago; and the He2 from 17.5 to 15.9 million years ago (Tedford et al., 2004). All of the Hemingfordian NALMA falls within the early Miocene Epoch of the standard geologic time scale.

Index species for He1 in Florida: Arenicolumba prattae, Desmocyon matthewi, Osbornodon iamonensis, Metatomarctus canavus, Cynelos caroniavorus, Amphicyon longiramus, Phoberocyon johnhenryi, Zodiolestes freundi, Floridachoerus olseni, Nothokemas floridanus, Floridatragulus dolichanthereus, Parablastomeryx floridanus, Parahippus leonensis, Floridaceras whitei, Menoceras barbouri

Significant He1 localities and faunas in Florida: Thomas Farm; Miller Site; Griscom Plantation; Seaboard Air Line Railroad Site; Oldsmar Shell Pit 2

Index species for He2 in Florida: Aletomeryx gracilis

Significant He2 localities and faunas in Florida: Midway Site; Dover Mine; Brooks Sink; Lower Gainesville Creeks Fauna; Suwannee Springs Site

Characteristic taxa for the Hemingfordian in Florida: Galeocerdo aduncus, Galeocerdo contortus, Batrachosauroides dissimulans, Bufo praevius, Rana miocenica, Hesperotestudo tedwhitei, Alligator olseni, Proheteromys floridanus, Harrymys magnus, Leptarctus ancipidens, Prosynthetoceras texanus, Machaeromeryx gilchristensis, Anchitherium clarencei, Archaeohippus blackbergi, “Merychippus” gunteri, Petauristodon pattersoni

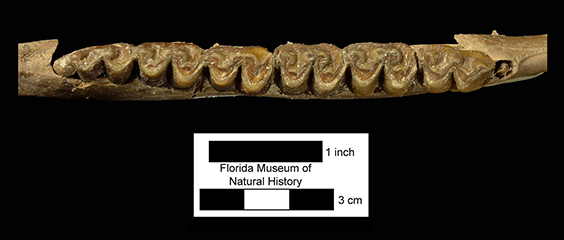

Gallery of Hemingfordian Florida Fossils

Major extinctions: Two artiodactyl families became extinct at the end of the He1, the Entelodontidae and Anthracotheriidae (Tedford et al., 2004). Many species of amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals are known only from the very rich He1 Thomas Farm locality. This gives rise to many apparent extinctions, as they are not known from the He2 or the following Barstovian. However, until vertebrate fossils from these ages are better known, it is not possible to conclude which of these extinctions are real and which are artifacts of a poor fossil record.

Comments: Thomas Farm has long been recognized as one of the richest and most diverse Hemingfordian faunas. In the correlation chart of Tedford et al. (2004), the age of Thomas Farm is shown as straddling the He1/He2 boundary. This differs from its placement entirely within the He1 in the corresponding chart of Tedford et al. (1987). There is no explanation in the text of Tedford et al. (2004) for this change. It is not clear whether their intent was to show that the age range of Thomas Farm extends from late in the He1 into the early part of the He2, or if they were unsure of the precise correlation between Thomas Farm and fossil faunas from western Nebraska, so that it could be either late He1 or early He2. There is no evidence of major faunal turnover in the excavated strata at Thomas Farm and the duration of deposition is thought to be rapid in terms of geologic time (Pratt, 1989). Thomas Farm contains at least four taxa listed by Tedford et al. (2004) as not surviving after the He1: Floridaceras, Menoceras, Phoberocyon, and Anthracotheriidae. Tedford et al. (2004) listed about 30 mammalian genera that are first known in the He2, and of these only one is present at Thomas Farm, the large gliding squirrel Petauristodon. Other than Thomas Farm, Petauristodon is also a member of the He1 Centenario Fauna of Panama (MacFadden et al., 2014), and tentatively has been identified at several Ar4 and He1 sites in southern California (Whistler and Lander, 2003). This suggests that the dispersal of Petauristodon from the Old World into North America occurred at least by the He1 and perhaps even earlier, and that its presence at Thomas Farm is not evidence for a He2 age. If Petauristodon is excluded, then there is no positive evidence that Thomas Farm is partially or completely He2 in age.

After Thomas Farm, the second largest Hemingfordian site in Florida is the Miller Site from Dixie County (Baskin, 2003; Wang, 2003). This locality has been exclusively excavated by commercial fossil dealers, and most of the best specimens have been sold to private collectors. A large, presumably representative sample of Miller Site fossils was purchased from the original collector by a private individual and then donated to the natural history museum at the University of Kansas. About 1,000 specimens have been donated to the Florida Museum of Natural History from this site. To date only a few of the carnivores have been described from the site, and in each case represent species not found at Thomas Farm. As at Thomas Farm, the most common larger mammal is a species of the horse Parahippus. The Miller Site Parahippus is more primitive than Parahippus leonensis from Thomas Farm, and represents a new species (O’Sullivan and Hulbert, 2014). The Miller Site also has a very large entelodont, a taxon not found at Thomas Farm. Thus Thomas Farm and the Miller Site are not likely to be contemporaneous, with Thomas Farm falling in the later half of the He1 and the Miller Site in the early half. Given the known duration of the He1, the difference in age between the two could be in excess of a million years.

The He2 interval is more poorly represented in Florida than the He1. The largest sample is from Brooks Sink in Bradford County (Pratt and Morgan, 1988). The terrestrial component of this sample is predominantly small mammals, reptiles, and amphibians. Only a preliminary report is available for this site, but the small mammals were said to be more advanced than those of Thomas Farm, and this is also the case with the horse “Merychippus” gunteri instead of Parahippus leonensis. “Merychippus” gunteri was named from the Midway local fauna of Gadsden County, the state’s other good He2 locality. Like most of the Miocene sites found in Gadsden County, the Midway Site was exposed by fullers earth mining operations. Fullers earths are clays with absorbant properties used to manufactor a wide number of products, including cat litter.

Sources

- Text Author: Richard C. Hulbert Jr.

- Image Gallery: Natali Valdes

- Original Publication Date: July 3, 2015

- Last Edited On: July 5, 2015

References

Baskin, J. A. 2003. New procyonines from the Hemingfordian and Barstovian of the Gulf Coast and Nevada, including the first fossil record of the Potosini. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 279(6):125-146.

Hulbert Jr., R. C. (ed.) 2001. The Fossil Vertebrates of Florida. University Press of Florida: Gainesville.

Hunt Jr., R. M. 2002. New amphicyonid carnivorans (Mammalia, Daphoeninae) from the early Miocene of southeastern Wyoming. American Museum Novitates 3385:1-41.

MacFadden, B. J., J. I. Bloch, H. Evans, D. A. Foster, G. S. Morgan, A. F. Rincon, and A. R. Wood. 2014. Temporal calibration and biochronology of the Centenario Fauna, early Miocene of Panama. The Journal of Geology 122(2):113-135.

McKenna, M. C. 1965. Stratigraphic nomenclature of the Miocene Hemingford Group, Nebraska. American Museum Novitates 2228:1-21.

Montellano-Ballesteros, M., and E. Jiménez-Hildalgo. 2006. Mexican fossil mammals, who, where, and when? Pp. 249-273 in F. Vega et al. (eds.), Studies on Mexican Paleontology. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

Morgan, G. S., and A. E. Pratt 1988. An early Miocene (late Hemingfordian) vertebrate fauna from Brooks Sink, Bradford County, Florida. Pp. 53-69 in F. C. Pirkle and D. S. Jones (eds.) Heavy Mineral Mining in Northeast Florida and an Examination of the Hawthorn Group and Post-Hawthorn Clastic Sediments. Southeastern Geological Society Field Trip Guide Book, No. 29.

O’Sullivan, J., and R. C. Hulbert Jr. 2014. A new parahippine equid from the early Miocene of Florida and the origin of cementum-coverd cheekteeth in horses. Pp. 134-135 in 10th North American Paleontological Convention Abstract Book. The Paleontological Society Special Publications 13.

Pratt, A. E. 1989. Taphonomy of the microvertebrate fauna from the early Miocene Thomas Farm locality, Florida (U.S.A.). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 76(1/2):125-151.

Tedford, R. H., T. Galusha, M. F. Skinner, B. E. Taylor, R. W. Fields, J. R. Macdonald, J. M. Rensberger, S. D. Webb, and D. P. Whistler. 1987. Faunal succession and biochronology of the Arikareean through Hemphillian interval (late Oligocene through earliest Pliocene epochs) in North America. Pp. 153-210 in M.O. Woodburne (editor), Cenozoic mammals of North America: Geochronology and Biostratigraphy. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Tedford, R. H., L. B. Albright III, A. D. Barnosky, I. Ferrusquia-Villafranca, R. M. Hunt Jr., J. E. Storer, C. C. Swisher III, M. R. Voorhies, S. D. Webb, and D. P. Whistler. 2004. Mammalian biochronology of the Arikareean through Hemphillian interval (late Oligocene through earliest Pliocene epochs). Pp. 169-231 in M. O. Woodburne, (ed.), Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic Mammals of North America, Biostratigraphy and Biochronology. Columbia University Press, New York.

Wang, X. 2003. New material of Osbornodon from the early Hemingfordian of Nebraska and Florida. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 279(8):163-176.

Wang, X., R. H. Tedford, and B. E. Taylor. 1999. Phylogenetic systematics of the Borophaginae (Carnivora: Canidae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 243:1-391.

Webb, S. D., R. C. Hulbert Jr., and W. D. Lambert. 1995. Climatic implications of large-herbivore distributions in the Miocene of North America. Pp. 91–108 in E. S. Vrba, G. H. Denton, T. C. Partridge, and L. H. Burckle (eds.), Paleoclimate and Evolution, with Emphasis on Human Origins. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Wood, H. E., et al. 1941. Nomenclature and correlation of the North American continental Tertiary. Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 52(1):1-48.