Each resident in Florida generates around 100 gallons of wastewater per day. This requires a massive effort of treatment and filtration for sustainable use. The solid waste that is filtered out becomes a byproduct of the process, called biosolids. Reclaimed wastewater and biosolids are piling up, with some areas in Florida offering reclaimed water for a virtually free or extremely low cost. Unfortunately, contaminants remain present in these resources despite the extensive treatment process, and the use of these could lead to unforeseen consequences. Such a widespread problem needs a collaborative solution.

To address the challenge of persistent contaminants in treated wastewater and biosolids, and the barriers they create for safe and efficient reuse, researchers at the University of Florida are developing innovative methods to remove and degrade these substances while also investigating safe and sustainable ways to reuse these resources. Over the past two years, the UF Water Institute has coordinated a cohort of scholars called the Beneficial Reuse of Wastewater and Solids (BREWS).

This interdisciplinary team of professors and students is collaborating to develop effective strategies for safe and sustainable reuse of reclaimed water and biosolids. From biogeochemistry to economics, the BREWS initiative brings together experts from diverse disciplines to advance research on this important topic.

Biosolids and Reclaimed Water: A Closer Look Down the Drain

When sewage arrives at a wastewater treatment facility, it undergoes a multi-stage treatment process that generates wastewater sludge at different steps. During initial treatment steps, heavier solids settle out of the wastewater, forming primary sludge. The remaining wastewater can undergo further biological treatment to breakdown suspended solids and pollutants, producing additional sewage sludge.

The combined solid waste is then treated using processes like dewatering to reduce the overall volume and composting to reduce pathogens. The final treated product is known as biosolids. When biosolids meet regulatory standards for pathogen reduction and pollutant limits, they can be applied to agricultural land as a nutrient-rich soil fertilizer, providing nitrogen, phosphorus, and organic matter that enhance soil health.

Many wastewater treatment facilities also include filtration and disinfection processes. Once treated wastewater meets a certain water quality standard, it becomes reclaimed water. This can be used as water for agriculture, lawn, and golf course irrigation, industrial cooling, or it can be reinjected into the aquifer.

Despite extensive treatment, biosolids and reclaimed water are not entirely free of contaminants. Phosphorus, nitrogen, and heavy metals are examples of chemicals that remain in the water and biosolids after treatment. While phosphorus and nitrogen are nutrients that plants need to grow, they can pose a risk to the environment, particularly through runoff and nutrient imbalance. Elevated concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus in water systems, for instance, can trigger harmful algal blooms, events that have led to aquatic species kills and raised human health concerns.

Other, more concerning contaminants are PFAS; nicknamed as “forever chemicals,” they refer to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances typically used in many household products, industrial processes, firefighting foams, food packaging, and more. Today, PFAS have reached global occurrence in our soil and water, and are especially prevalent in both our wastewater and biosolids.

PFAS have been associated with several adverse health risks. Because of their unique chemical composition (strong carbon-fluorine bond), PFAS are difficult to break down and be removed from substances like wastewater and biosolids.

Biochar and PFAS Breakdown

To tackle the main issue around the presence of contaminants in biosolids and wastewater, researchers have identified a promising solution for PFAS and heavy metal remediation.

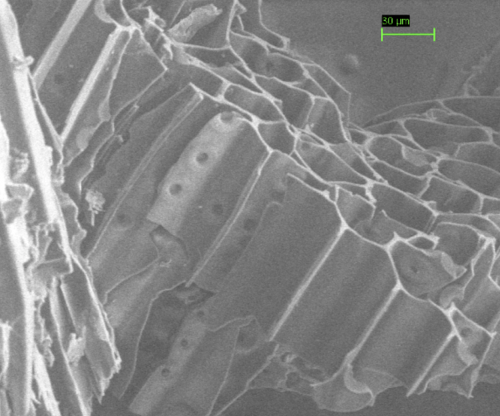

Dr. Andrew Zimmerman is an organic geochemist and biogeochemist professor in the UF Department of Geological Sciences. His research focuses on organic matter transformed by fire, referred to as biochar. Because of its stability, biochar has been widely used as a carbon sequestration tool. “Depending upon the biochar, most of it (not all) will likely remain in the soil for 100 to 1000 years,” said Zimmerman.

“Biochar is also a highly porous substance which can be used to mitigate PFAS and other contaminants like heavy metals. Biochar, when co-applied with biosolids, can absorb and possibly degrade some of the PFAS,” Zimmerman discussed.

As part of the BREWS initiative, Dr. Zimmerman collaborates with Dr. Katherine Deliz, an environmental chemist at the UF Engineering School of Sustainable Infrastructure and Environment, with expertise in analyzing PFAS and heavy metals in soil and water. Dr. Deliz leads research on contaminant treatment technologies and has developed advanced methods for detecting and understanding contaminant behavior, such as PFAS, in complex environmental samples.

Together, they are testing cutting-edge approaches—like heating (pyrolysis) and grinding (mechanochemical degradation)—to transform biosolids into safe, nutrient-rich soil amendments. Their work could help turn waste into a valuable resource, improving soil health, reducing fertilizer costs, and protecting Florida’s water quality.

I see these treatment approaches as true circular economy solutions, where municipal wastewater treatment facilities could become resource recovery centers, generating income from materials that were previously a disposal challenge.

— Dr. Katherine Deliz

“The hope is that […] breakdown of the biochar-adsorbed PFAS will take place over several years,” noted Zimmerman. Further research is underway, so “because biochar has electron conducting properties, and microbes love to colonize the surfaces and pores of biochar,” the outlook is positive on the success of future PFAS breakdown.

Reclaimed Water and Biosolid Applications

Due to the high concentration of nutrients in biosolids and reclaimed water, they both make a great fertilizer for farm fields and residential lawns.

Dr. Davie Kadyampakeni is an associate professor in Citrus Water and Nutrient Management in the UF Department of Soil, Water, and Ecosystem Sciences (SWES). His work focuses on the agricultural application of reclaimed water.

“We have been working on different kinds of reclaimed water. And looking at how blueberries respond in terms of salinity, production, and growth.” He also works with biochar and compost applications to improve soil health and crop productivity.

When working with reclaimed water, Dr. Kadyampakeni noted that it, “has very high [levels of] nitrates or phosphates.”

During his research, he found that despite these high concentrations, reclaimed water can be used on crops and applied to yards for grass lawn watering.

Dr. Kadyampakeni hopes to collaborate with farmers and continue working with biochar to explore its benefits. “I want to make sure I’m able to test this on a farmer’s field,” he shared, “using biosolids, using biochar, using compost.”

Expanding the scope beyond farm fields, Dr. Mary Lusk, an assistant professor in UF SWES, works with urban nutrient management in watersheds, and investigates how reclaimed water contributes to nutrient runoff and its impact on water quality

In Florida’s residential areas of single family detached homes, lawn irrigation uses 991 gallons of water per irrigation cycle – the equivalent of running your bathroom sink for over eight hours, according to UF/IFAS. With water conservation and cost considerations, many Florida residents are choosing to use reclaimed water on their lawns.

As reclaimed water is applied to residential lawns, some of it will run off into the watershed, contaminating the waterways with excess nutrients which can lead to harmful algal blooms. Dr. Lusk discussed how poor irrigation behaviors are affecting the water quality in local Florida water systems.

She called for increased collaborative partnerships and communication with Florida residents to limit excessive use of reclaimed water, especially near major waterways. Dr. Lusk will continue to explore the implications of future population growth in urban areas and how that relates to water use and quality. As more individuals use reclaimed water, her research will examine methods to ensure that it remains sustainable and safe to use.

Together, Dr. Kadyampakeni and Dr. Lusk are helping to advance understanding of the agricultural and residential implications of biosolids and reclaimed water reuse.

Balancing Waste Reuse with Ecosystem Safety

The BREWS team is also exploring how wastewater and biosolid reuse may affect ecosystems and human health. Understanding these environmental impacts helps researchers anticipate potential risks to people, especially when contaminants like PFAS or heavy metals are involved.

Dr. AJ Reisinger of UF SWES and Dr. Joe Bisesi of the UF College of Public Health and Health Professions are collaborating to understand and reduce the long-term environmental impacts of biosolids application on aquatic ecosystems. Their research adds an environmental and public health component to the broader issue of contaminants in Florida watersheds due to biosolid applications and wastewater reuse.

Together they plan to combine field studies in the Upper St. Johns River Watershed with controlled experiments to assess how nutrients and contaminants—such as PFAS, pharmaceuticals, and heavy metals— might change the quality of the water and affect the plants and animals living in it.

They will use a mix of water quality monitoring, wildlife observations, and ecosystem tracking to better understand how biosolids affect the environment. “Through this collaboration, our goal is to create clear, science-backed guidelines that help communities make safer decisions about biosolid use,” said Dr. AJ Reisinger.

Dr. Reisinger and his team are also looking at how artificial wetlands respond to reclaimed water addition to enhance their pollutant removal.

Scalability and Economic Implication

As biosolids and reclaimed water are adopted into land and water infrastructure, it becomes necessary to understand not only the environmental and health implications but also their economic feasibility.

Dr. Kotryna Klizentyte is an assistant professor of Natural Resource Economics and Policy at the UF School of Forests, Fisheries, and Geomatic Sciences. On the BREWS team, her research focuses on the non-market value of clean water and the negative economic consequences of PFAS — “so not only am I looking at the economics of it, but [I’m also] looking at the social aspects of it as well.”

There are many factors to consider when choosing how to apply biosolids to farmlands, properties, and landfills. “Biosolids, [are] more ecologically sound and efficient, but […] how do we actually create a marketable practice that makes economic sense?”

It is important to understand the feasibility of the production, shipping, and application costs of biosolid use in each of these settings. She noted that “there are some bottlenecks with […] the economic supply chain, [with] scalability.”

Additionally, her concern with PFAS is that despite successful research with biochar, “it’s not realistic [for] 100% of the PFAS [to be] gone at any cost.” The spread and longevity of PFAS presence is already extreme.

Additionally, there is growing social concern over biosolid application, as it becomes “a NIMBY (not in my backyard) problem.”

In her future research Dr. Klizentyte hopes to partner with industry professionals, collaborating to find a realistic and applicable path to safe, effective, and sustainable biosolid applications.

Moving forward

The BREWS team will continue to work on the emerging and widespread issue of PFAS and contaminants in wastewater and biosolids as it continues to present significant challenges to environmental health, agricultural safety, economy, and public health.

Despite the extensive treatment of our waste, PFAS and other contaminants remain and leach into the environment regardless of landfill or soil application. With the interdisciplinary collaboration across the BREWS team, promising solutions like biochar applications are being explored.

From biogeochemistry to economics, these researchers will work together to mitigate PFAS contamination and promote safe reuse practices. With further collaboration and future regulatory support, biosolids and reclaimed water can be safely and sustainably used in residential, agricultural, and environmental systems.