A 2018 YouTube video shot as the center of Hurricane Michael passed over Mexico Beach opens with the fumbling of a camera.

Then, it portrays a moment of peace in a scene of utter destruction. This was the first Category 5 hurricane to pinwheel through the U.S. since the ‘90s.

The GoPro camera sits on the roof of a car, a road stretched in front into the distance. Each side of the asphalt is lined with trees snapped in half and keeled to the ground.

The sky above, however, is the most curious part: A perfect dome of clouds surrounds the vehicle in a heavenly circle.

It’s called “the stadium effect” — and it’s a feature of fully developed tropical cyclones, or hurricanes.

State climatologist David Zierden opened his Jan. 29 presentation at the University of Florida with a still picture from the sobering video. The sight “hit hard and was a little personal,” said the Panama City native.

“As a full-fledged weather nerd all my life, experiencing the eye of a major hurricane was always on my bucket list,” he said. “After seeing the damage in this, I’m very fine with just seeing it on video.”

Zierden, who was appointed as state climatologist in 2006, researches local climate forecasts and what those predictions might mean for the state’s resources and industries. On that Wednesday evening in January, he traveled from Florida State University’s Florida Climate Center to address Florida’s changing climate at UF’s packed Gannett Auditorium.

This extreme weather event, the impacts of which still disrupt daily life in the area 18 months later, won’t be the last, Zierden said. Hurricanes are just one of the looming weather threats facing Florida, along with sea level rise, temperature fluctuations, droughts and rainfall. These factors each cyclically impact each other — all pieces that make up the overarching puzzle, and problem, of climate change.

While the average number of tropical cyclones per year has remained the same around the world, he said that they are getting stronger — and slower, which means the exposure to destruction will linger. Their more powerful winds prompt ocean water to rise up and flood coastal areas, a phenomenon known as storm surge.“This is a grand experiment that we’re doing on the planet,” Zierden said. “But we really don’t know where it’s going.”

The rise of these slow-moving, intense storms is partly due to the effects of climate change. Climate change is largely driven by the increase of a colorless, odorless gas in our atmosphere known as carbon dioxide. Excess carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere can enhance what’s known as the greenhouse effect — a process in which atmospheric gases trap the sun’s heat — leading to warmer global temperatures. Data from the Mauna Loa Observatory show that atmospheric carbon dioxide has increased by 30% from 1960 to present day. Zierden said this is the direct result of human activity, such as the of burning fossil fuels, like coal, oil and natural gas.

Using ice cores drilled from Antarctica, scientists can sneak a peek at carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere from the past million years. Their findings show that despite Earth’s long history with fluctuating conditions, including several Ice Ages, carbon dioxide levels have never been this high, Zierden said – and they are expected to keep rising.

“This is a grand experiment that we’re doing on the planet,” he said. “But we really don’t know where it’s going.”

The last five years have been the hottest on record, Zierden said. Last year was the second-warmest year, only beaten by torrid temperatures in 2016.

Florida is not excluded from this worldwide narrative: 54 out of the last 57 months have been warmer than average in the state. Nighttime temperatures have steadily increased, and winter temperatures have fluctuated throughout the years.

These rising temperatures can harm crop yields that aren’t accustomed to the changing climate. But the warmer temps also have produced one interesting shift — the range of citrus trees is beginning to expand to once again include typically cooler North Florida.

Zierden said the last devastating freeze to the Florida citruses occurred in 1997. The industry has remained largely unscathed by the cold ever since.

“The question is: Are these [freezes] going to be a thing of the past with climate change?” he asked. “I think that’s a possibility.”

While temperature patterns are somewhat steady, precipitation levels are “where it gets a little muddier” to find clear trends, Zierden said. Rainfall and droughts are more uncertain and difficult to predict, though meteorologists have witnessed a general increase in drought frequency and destruction.

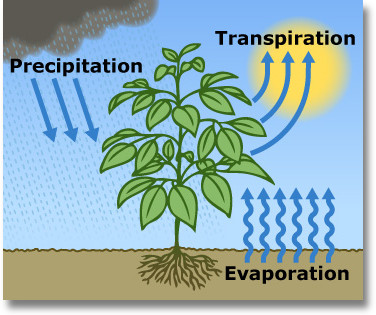

Even if rainfall remains the same, increased temperatures and evaporation and transpiration from plants will deplete limited water supplies and create longer, more severe periods of drought, Zierden said.

This variation between rainfall and droughts is often swayed by two forces in the Pacific Ocean: El Niño and La Niña.

El Niño events arise when changes in atmospheric circulation lead to warmer sea surface temperatures in the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean. These warmer waters set off a cascade of events, including more storms across the southern U.S. During this time, Florida can see 40% to 60% more rainfall, said Zierden.

Adversely, La Niña occurs when atmospheric changes lead to cooler sea surface temperatures in the tropical eastern Pacific. La Niña events cause rainfall across the northern U.S., leaving Florida and the rest of the Southeast in a state of drought with drier and warmer conditions.

“When we have El Niño in place, we’re usually several degrees colder than normal due to increased cloudiness and rainfall,” he said. “During La Niña phases, we’re several degrees warmer than normal during the winter months.”

Beyond causing changes in temperature, rainfall, and drought, increases in ocean temperature are also leading to sea level rise. Sea level has been in a well-known upwards climb in recent years, and will continue to rise between 1 and 4 feet by 2100, Zierden said. This increase is due to two processes: the warming of oceans and the melting of ice sheets and glaciers.

Rising waters threaten drinking water supplies, overwhelm sewer systems and complicate commutes. In Miami-Dade County, for example, the groundwater levels in some areas are lower than the rising sea levels. This difference has allowed saltwater to intrude into the drinking water supply.

The state climatologist concluded his talk with some “words of life” to round out the scary predictions of our Earth’s future. Despite the environmental missteps of the past and any current damage still ensuing, political and personal choices are morphing, Zierden said.

Broad global policy changes, especially those in the U.S. and in Florida, are necessary to the fight against this seemingly invisible yet impactful global transformation.

“The more we do — and the sooner we do it — hopefully, the less harsh the impacts of climate change are, and the more adaptable we are to them,” he said.