Thirty years ago, the Everglades was a much different place than it is today. At one time, people could go and see wildlife of all sizes, but today something is missing. Many mammals used to call the Everglades home, but now, rabbits are few and far between, raccoon tracks have all but disappeared, and foxes and panthers, which used to control these populations, are hard to come by. Their absence itself is the story — one shaped by an invader few Floridians ever saw coming: the Burmese python.

How Florida Became Ground Zero

Florida is a biological hotspot. Its sub-tropical and tropical climates, extensive wetlands, and fragmented landscapes provide grounds for non-native and native species to thrive.

Today, Florida is home to more invasive animal species than any other U.S. state, and only California surpasses it in overall invasives. These invasive species are organisms introduced outside their native range that disrupt the ecosystems they enter. Many of these species were introduced accidentally through global trade, while others arrived intentionally through the exotic pet industry or horticulture. Florida’s role as the global hub of the reptile trade and the gateway for nearly 75% of all plants imported into the U.S. only intensifies the invasion problem.

As Analise Fussell, a master’s Student in the Global Ecology Research Group at the University of Florida, explains, “Our climate and geographic location make this a prime place. The exotic pet trade has definitely exacerbated this. Reptiles and amphibians just thrive, and Florida laws are just too lax to combat this.”

With Florida’s warm weather and status as an exotic trade hub, reptiles and amphibians flourish here. Iguanas bask on seawalls, Cuban treefrogs colonize backyards, and Nile monitors stalk canals. Yet among them, the Burmese python stands out as one of the most destructive and emblematic cases of biological invasion in the modern United States.

From Curiosity to Catastrophe

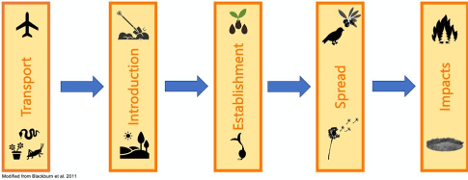

Following the typical pattern of invasive species, the python did not become successful overnight. It followed stages: transport, introduction, establishment, spread, and finally, impact.

The Burmese python illustrates each of these stages. First introduced to Florida through the pet trade, their spread was likely exacerbated by Hurricane Andrew (1992), which destroyed a breeding facility. From there, the species quickly moved from curiosity to catastrophe. By the time we noticed this well-hidden species, it was too late for an easy removal -– like many other reptiles and amphibians.

The first sighting of a python in the Everglades was between 1980 and 1990, but by the early 2000s, scientists had confirmed the presence of a breeding population. By this point, they were listed as invasive, creating an irreversible turning point.

Burmese pythons have found a foothold in the Everglades. “They’re just so good at hunting, hiding, and surviving here,” Fussell says. “They seem like they were made to be in this type of environment.” And it’s not going to be an easy management path.

Meet the Burmese Python

Native to Southeast Asia, the Burmese python (Python bivittatus) is one of the largest snakes on Earth, capable of growing over 18 feet long and weighing more than 200 pounds. In its native range, it is an apex predator, keeping populations of small mammals, birds, and reptiles in check.

In Florida, however, its size and adaptability have made it a super-predator in a system with no natural checks. Its generalist behavior (ability to prey on anything), and cryptic coloration (amazing camouflage) have allowed the Burmese python to thrive and consume everything in its way.

The numbers alone tell a story: more than 23,000 Burmese pythons have already been removed from Florida. Yet biologists estimate that represents but a fraction of the population, as only 1% of Burmese pythons are ever seen or captured. Their stealth has allowed them to spread silently through Everglades National Park, Big Cypress National Preserve, and surrounding areas.

Learn more about them in a previous TESI Tell Me About.

Native Wildlife in Collapse

In the approximately 40 years since the establishment of Burmese pythons, meso-mammals (medium sized mammals) have declined by over 90%. Since 1997 raccoons have declined by 99.3 percent, opossums by 98.9 percent, and bobcats by 87.5 percent, with marsh rabbits, cottontail rabbits, and foxes now considered extirpated (locally extinct) from most areas of successful python invasion.

This collapse of wildlife does not stop with small mammals. With prey vanishing, the already endangered Florida panther struggles to find food. Birds, reptiles, and amphibians face growing predation pressures. The Everglades food web is unraveling, because of invasive species.

The Invisible Enemy: Snake Lungworm Disease

Burmese pythons brought more than just their fangs. Researchers discovered an Asian lungworm parasite (Raillietiella orientalis) hitchhiked into Florida with them.

Burmese pythons brought more than just their fangs. Researchers discovered an Asian lungworm parasite (Raillietiella orientalis) hitchhiked into Florida with them.

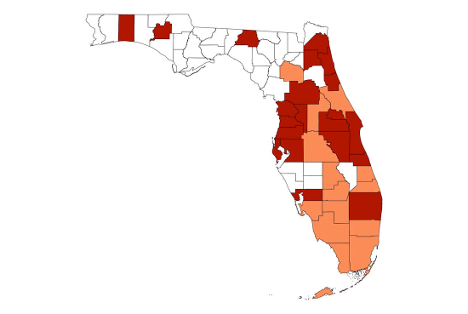

Ashlynn Canode, a master’s student at UF studying snake community composition and pathogens, explains, “It is caused by a parasite called R. orientalis. The lung for a python is much larger than native snakes, and so it’s detrimental to native species. Now, in about 35 counties snakes are infected and dying from this lungworm.” R. orientalis is a large parasite that can completely infect the lung of native snakes, unlike the python which has a larger lung comparatively.

Native snakes like banded water snakes and black racers are particularly affected. Lesions, nodules, and even visible worms emerging from dead snakes mark the infection. The parasite spreads through a complex life cycle, beginning in python feces and passing through insect, amphibian, and mammal intermediate hosts before infecting other snakes as the final hosts.

While research is ongoing, Canode stresses the difficulty: “There’s not really a way to treat lungworms in wild populations. Right now, it’s mostly biosecurity and reporting. If you’re road-cruising and you see white worms coming out of a snake’s mouth, you should report it on the SLAM (Snake Lungworm Alliance & Monitoring) website.”

Maps released in 2025 show its range spreading beyond South Florida.

Learn more about snake lungworm disease here with a previous TESI Tell Me About.

Innovative Solutions to Combat Burmese Pythons

Florida isn’t giving up. Researchers and wildlife managers are testing every tool imaginable to find these hidden snakes:

- Scout snakes: radio-tagged male pythons lead hunters to hidden breedin

- Sniffer dogs: specially trained canines sniff out pythons in dense brush.

- Robotic rabbits: mechanical rabbits lure snakes into range and when they attack the robot, it sends a GPS signal.

- Public hunts: the annual Python Challenge rallies hunters and naturalists alike. There are also organizations that work on python removal year-round.

In 2025, Nearly 1,000 participants from across North America removed a record 294 snakes in just 10 days. While the Challenge generates public awareness, experts stress that it is not a solution. The population is too large, and annual removals barely dent the total number of snakes. As Analise cautions, “Long-term management is the realistic way. Eradication isn’t feasible.”

Pythons are just the Surface

There is an underscoring lesson to be learned through the python invasion: prevention is much more effective and cheaper than control. The Burmese python has reshaped the heart of South Florida.

While pythons dominate headlines, experts warn against ignoring less “charismatic” invaders like Argentine black-and-white tegus or invasive plants such as Brazilian pepper. “I think the plants can be more detrimental than the animals,” Analise notes, “because of how fast they spread and how little the public understands their role in ecosystems.”

Once a species is established, eradication is nearly impossible. Public education, stricter pet trade regulations, and early detection are the best tools for stopping the next python before it takes hold.

Ashlynn sums up the stakes: “In terms of pythons, they are just so well established and likely to move north as climate change progresses. It’s likely we’ll see more impacts than we already do.”

The Road Ahead

Ultimately, the story of the Burmese python in Florida is not just about one species. It is about how prevention, policy, and public awareness are essential to avoiding future invasions.

“People need to understand that invasive species are a very significant problem,” Analise reflects. “Policy needs to become stronger, so the Everglades doesn’t become even more of an invasion ground. And that starts with education — understanding what goes on in and around our backyard.”

The Everglades remains a focal point for both the consequences of past environmental change and the challenges that lie ahead. Rather than representing a loss, it offers an opportunity to learn and adapt. Successful restoration in the Everglades could inform and inspire similar efforts worldwide.

Meet the Interviewees

Analise Fussell is a master’s student at the University of Florida in the School of Natural Resources and Environment. She is a member of the Global Ecology Research Group where she researches wading birds in South Florida, from a fieldwork and citizen science data perspective. Previously, she was a member of the Croc Docs Wildlife Research Team at UF, where she investigated removal and management strategies of invasive herpetofauna species.

Analise Fussell is a master’s student at the University of Florida in the School of Natural Resources and Environment. She is a member of the Global Ecology Research Group where she researches wading birds in South Florida, from a fieldwork and citizen science data perspective. Previously, she was a member of the Croc Docs Wildlife Research Team at UF, where she investigated removal and management strategies of invasive herpetofauna species.

Ashlynn Canode is a master’s student at the University of Florida in the department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation. She researches changes in snake community composition over time and pathogen presence in North Florida snake populations. She is heavily involved in field research at Tall Timbers in Tallahassee, Florida.

Ashlynn Canode is a master’s student at the University of Florida in the department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation. She researches changes in snake community composition over time and pathogen presence in North Florida snake populations. She is heavily involved in field research at Tall Timbers in Tallahassee, Florida.

About the Author

This story was produced by Levi Hoskins , a student environmental communicator with the UF Thompson Earth Systems Institute (TESI). TESI’s mission is to advance communication and education about Earth systems science in a way that inspires Floridians to be effective stewards of our planet.

This story is part of TESI’s student-produced Earth to Florida newsletter that curates the state’s environmental news and explains what’s going on, why it matters and what we can do about it.