Abigail Davis, UF ’27

Abigail Davis, UF ’27

Environmental Science BA Major

TESI Environmental Leaders Intern: UF Biodiversity Institute (Fall 2025)

TESI Environmental Leaders Fellowship Florida Springs Outreach Intern (Spring 2025)

Abigail Davis is pursuing a Bachelor of Arts degree in environmental science with a minor in agricultural and natural resource communication. She is passionate about using her voice for good through environmental stewardship and effective altruism.

In her free time, Abigail likes to be on the go. She enjoys social run clubs, weekend backpacking trips, line dancing, and arts and crafts. In TESI, she looks forward to honing her skills in education and outreach, all revolving around the wonders of Florida.

Sponsored in partnership with the UF Biodiversity Institute, Abigail will work with the UF Biodiversity Institute and TESI to communicate biodiversity-related topics this semester. She will highlight ongoing research through outreach content.

Content by Abigail:

View all

Know Your Florida Instagram Posts (@knowyourflorida)

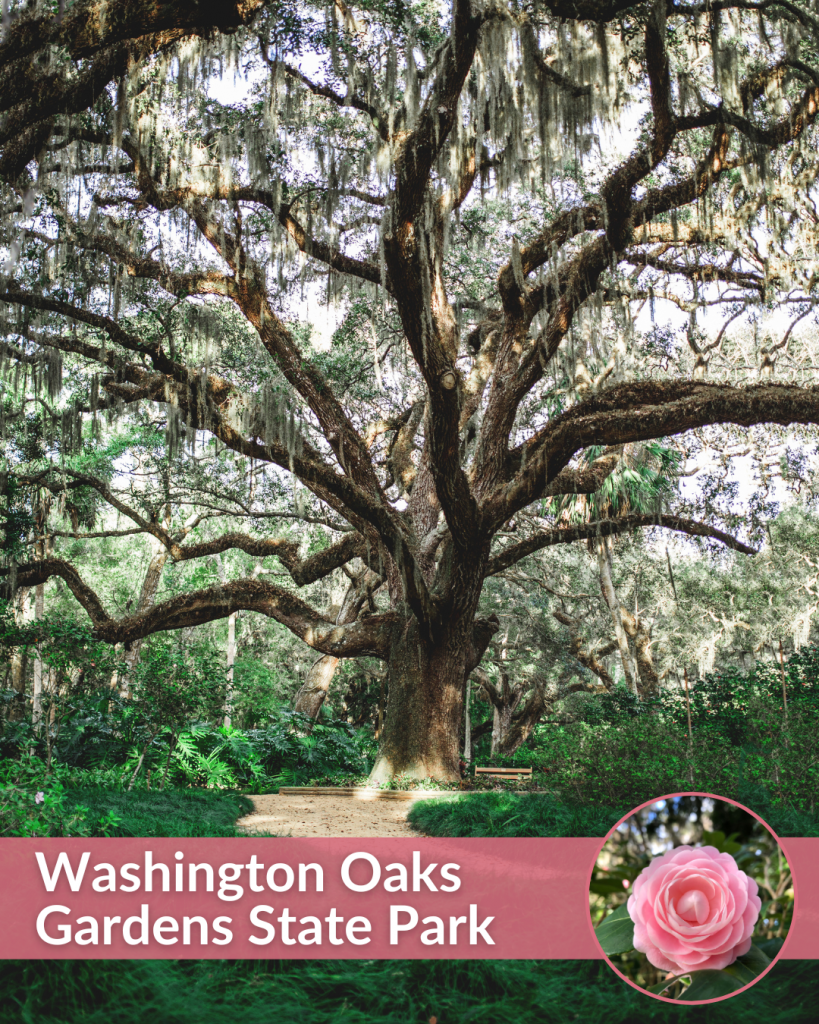

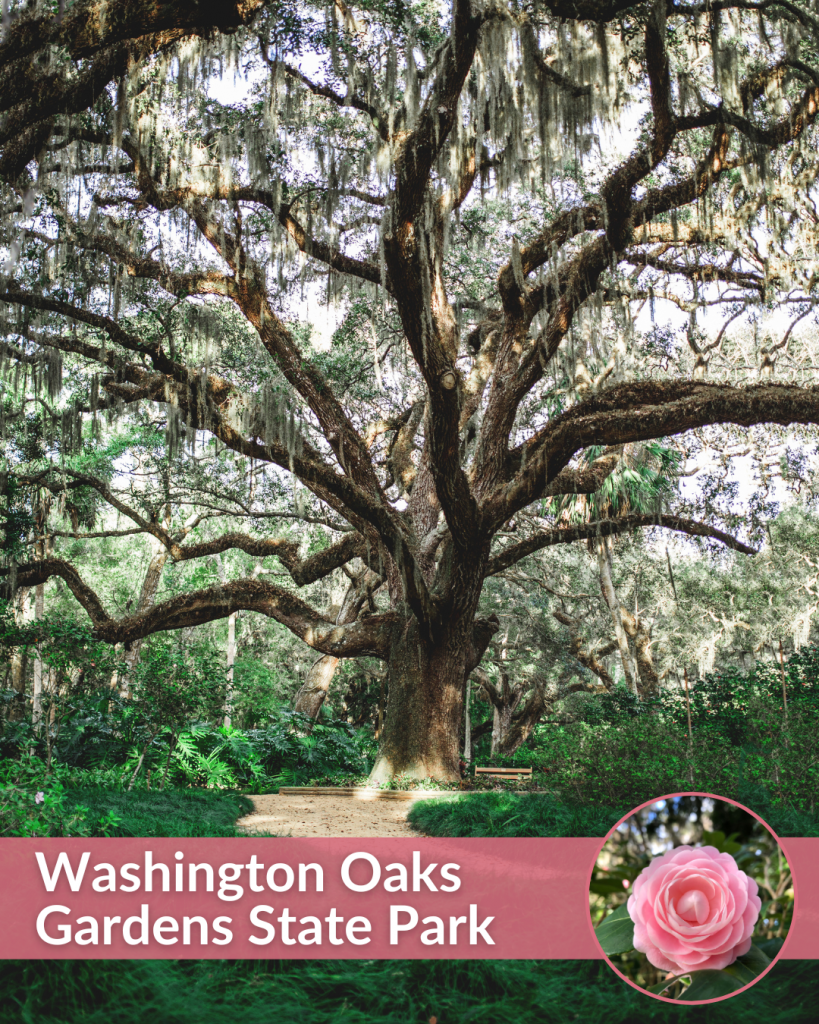

Washington Oaks Gardens State Park, located in Flagler County near the town of Palm Coast, boasts a biodiverse landscape across its 425 acres. 34 imperiled species call the natural communities of the state park home, including the scrubby flatwoods, maritime hammocks, and coastal strands. Washington Oaks Gardens also showcases famous formations of coquina rock, a rare sight along Florida’s Atlantic coast. These natural outcrops host at least 100 species of plants and animals. Nestled within the park, vibrant gardens showcase a stunning array of azaleas, camellias, and roses, adding color and charm to this valuable landscape. At its heart stands the majestic Washington Oak called “Oka,” a living giant estimated to be 200 to 300 years old. This live oak tree symbolizes resilience, having weathered centuries of hurricanes, fires, droughts, and floods. Information from Florida State Parks, Things in Florida, and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Large photo from Canva Pro. Small photo by Abigail Davis. #KnowYourFlorida #StatePark #BiodiversityInstitute #ThompsonEarthSystemsInstitute #WashingtonOaksGardens

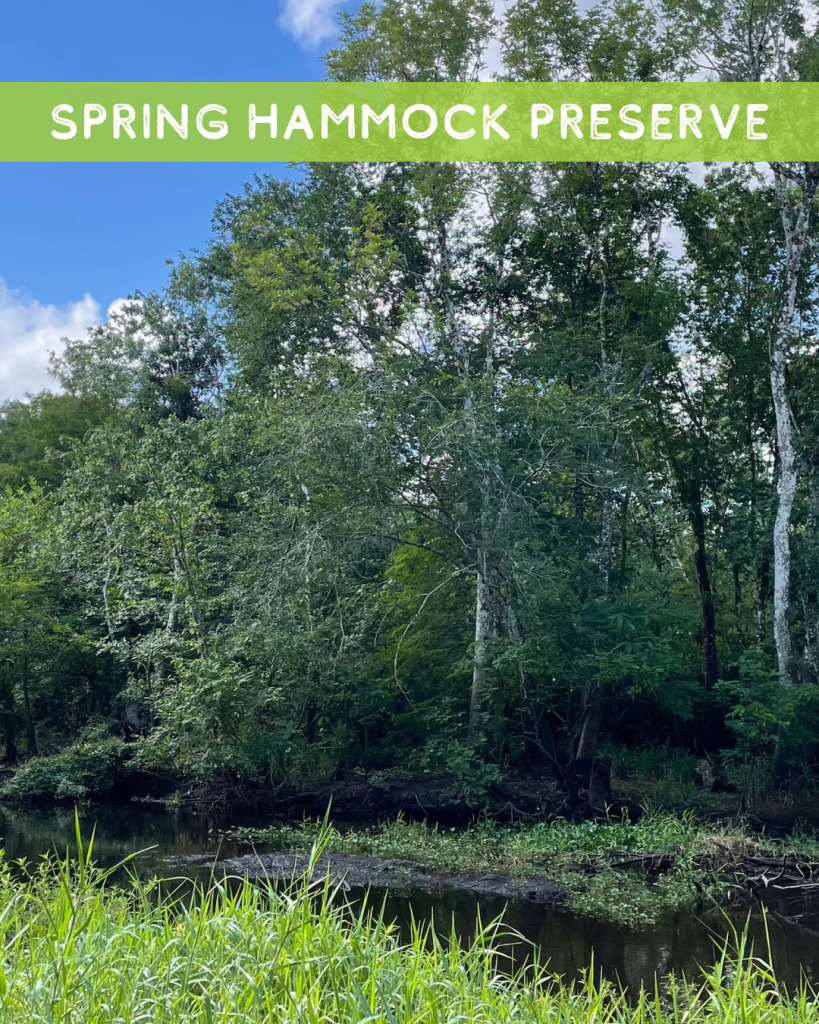

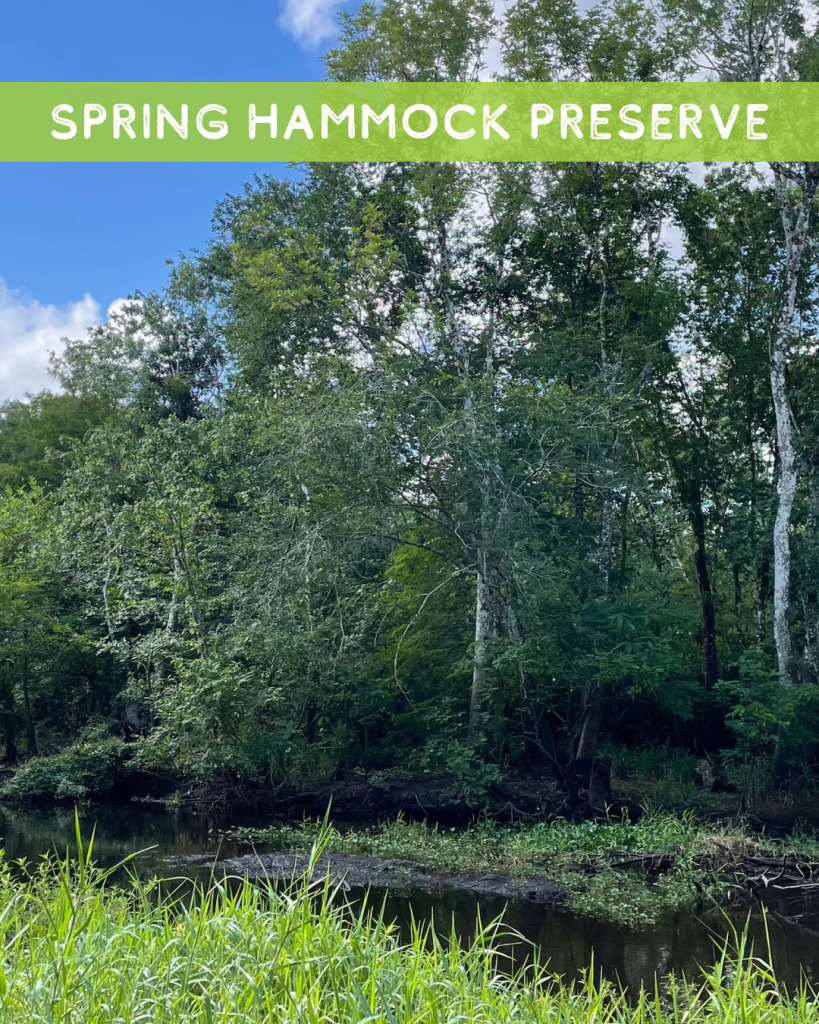

Nestled in Florida’s city of Longwood, Spring Hammock Preserve is a vibrant haven of native wildlife and plant life. Following a recent revitalization, the preserve now offers even more opportunities to experience Florida’s rich ecological features. The Osprey Trail, which opened in 2025, provides immersive access to the old-growth floodplain forest ecosystem, where biodiversity thrives. As you hike, keep an eye out for American alligators, wading birds, cypress knees, cabbage palms, and a variety of other native species that call this landscape home. One of the Preserve’s most remarkable features is that it is one of the southernmost areas where you can see the tulip poplar tree, a rare botanical gem in the region. Spring Hammock also hosts the gopher tortoise (a keystone species) and the endangered Okeechobee gourd. Whether you are a seasoned naturalist, a curious explorer, or simply seeking a peaceful escape, Spring Hammock Preserve contributes to an array of Florida’s natural heritage. Information from the Old Growth Forest Network and Florida Hikes. Image by Abigail Davis. #KnowYourFlorida #SpringHammockPreserve #BiodiversityInstitute #ThompsonEarthSystemsInstitute #FloodplainForest

Nicknamed the “Goldilocks bird,” the Cape Sable seaside sparrow lives exclusively in the habitat of the marl prairie of the Everglades. Conditions must be just right for it to survive and thrive! When the sparrows build their nests half a foot above the ground, they protect themselves from the threats of floodwater or predation by rats and snakes. However, a large increase in water levels caused by environmental shifts provides an ongoing challenge to the sparrows. Sometimes, the males even stop singing. While the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has recognized this bird as endangered since 1967, restoration efforts are in effect. One long-term project, known as Joint Ecosystem Modeling (JEM), aims to develop ecological forecast models for the Everglades. The Cape Sable seaside sparrow provides valuable information on Everglades biodiversity by indicating the potential response of the marl prairie habitat to changes in hydrology. The marl prairie has clumped grasses, open areas for sparrow movement, and seasonal water retention. Information from the Center for Biological Diversity, USGS, and the National Park Service. Photo by Lori Oberhofer of the National Park Service. #KnowYourFlorida #CapeSableSeasideSparrow #BiodiversityInstitute #ThompsonEarthSystemsInstitute #Goldilocks

Looking for a winter escape surrounded by Florida’s wildlife? Look no further! The Lake Apopka Wildlife Drive lets visitors explore Lake Apopka North Shore and a wide variety of native species at their own pace. Traveling on the 11-mile, one-way road on the eastern portion of the property takes between 1-3 hours, depending on how often you stop for wildlife viewing. Home to 377 bird species—150 in winter—Lake Apopka North Shore is a holiday hotspot for birders. Since 1988, it has held the one-day inland Christmas Bird Count record, logging 174 species. Could 2025 set a new one? This site ranks among Florida’s top three birding destinations alongside the Everglades and Merritt Island. Celebrate the season with herons, egrets, warblers, and flycatchers. If you’re not a birder, the 20,000-acre property also boasts American alligators, bobcats, otters, bears, raccoons, armadillos, and coyotes. Fed by a natural spring, rainfall, and stormwater runoff, the state’s fourth-largest lake, Lake Apopka, is worth the drive. Are you up for the adventure? On an upcoming weekend or federal holiday, take a road trip through the restored marsh, wetland, and floodplain habitat full of biodiversity! Use the Lake Apopka Wildlife Drive Audio Tour provided by the St. Johns Water Management District to learn more across 11 audio tour stops. Information from the St. Johns Water Management District. Photo courtesy of Abigail Davis. #KnowYourFlorida #LakeApopkaWildlifeDrive #BiodiversityInstitute #ThompsonEarthSystemsInstitute #CentralFlorida

Ever wonder what feeds on pesky roaches? Easily mistaken for the Broad-Headed Skink, the Southeastern Five-Lined Skink is a Florida native lizard that thrives in moist habitats. While adapted to life on the ground, it can also climb skillfully. This lizard has a thick neck, sprawling legs, and can grow up to 8.5 inches in length. It eats a variety of foods, including roaches, worms, small lizards, other insects, spiders, amphibians, and snails. Juveniles have five stripes on a black body, with the stripes changing from yellow at the head to blue at the tail. This color contrast helps young skinks avoid predators. Adults have a red-brown head with their color becoming drabber towards the tail, sometimes with faint lines. To evade predators, adults can shed their tails in a process called autotomy. Skinks play an important role in Florida’s biodiversity by controlling insect populations and serving as prey for larger animals. Losing them would disrupt this balance and harm the health of our ecosystems. There are other dangers skinks face, not just natural predators! If you’re a cat owner, please keep your cats away from skinks. If you’re a hiker, stay on the trail and watch your step—these lizards often hide under fallen leaves. Information from Florida State Parks and UF/IFAS Blogs. Top photo by USGS. Bottom photo by kingr via iNaturalist (CC-BY-NC). #KnowYourFlorida #Lizard #BiodiversityInstitute #ThompsonEarthSystemsInstitute #Native

Have you ever wanted to watch a sea turtle lay eggs? You can do so responsibly with a tour guide at Canaveral National Seashore, located in Brevard County, Florida. Check their website during the sea turtle nesting season (April through October) for updates on opportunities. Known as the longest stretch of undeveloped Atlantic coastline in Florida, Canaveral’s shoreline spans 24 miles—an ideal place for sea turtles to nest. Loggerhead and green sea turtles make regular appearances, while leatherback sea turtles show up occasionally. Altogether, these species lay eggs in about 4,000 to 7,000 nests on the beach each year. Although rare, Kemp’s ridley and Hawksbill sea turtles have also been documented. Canaveral is more than a nesting ground—it’s a powerful representation of biodiversity. All five sea turtle species found here are either threatened or endangered, and the park provides habitat for 15 federally listed species, ranking it second in the entire National Park Service for such diversity. Information from the National Park Service. Photo by the National Park Service (MTP 19-005). #KnowYourFlorida #SeaTurtles #BiodiversityInstitute #ThompsonEarthSystemsInstitute #CanaveralNationalSeashore

Did you know there’s a paved trail that stretches from the Gulf Coast on Florida’s west side all the way to the Atlantic Ocean on the east? Florida’s Coast-to-Coast makes it possible, spanning an impressive 250 miles. As of February 2025, about 88% of the trail was complete, already linking scenic areas like Richloam Wildlife Management Area, Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, and Croom Wildlife Management Area. Traveling from sea to sea can take several days by bike. According to the Florida Coast to Coast (C2C) Trail public Facebook group, the route features hard-packed limestone and black sand, adding unique character to the journey. Followers have reported spotting a variety of wildlife along the way, including otters, turtles, deer, snakes, armadillos, and even alligators. Whether you’re taking a leisurely self-care walk or racing to the finish, the C2C trail offers a special look into Florida’s diverse landscapes and ecosystems—from one coast to the other! Information from the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, and the Florida Coast to Coast (C2C) Trail public Facebook group. Photo by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. #KnowYourFlorida #FloridaTrail #BiodiversityInstitute #ThompsonEarthSystemsInstitute #CoasttoCoast

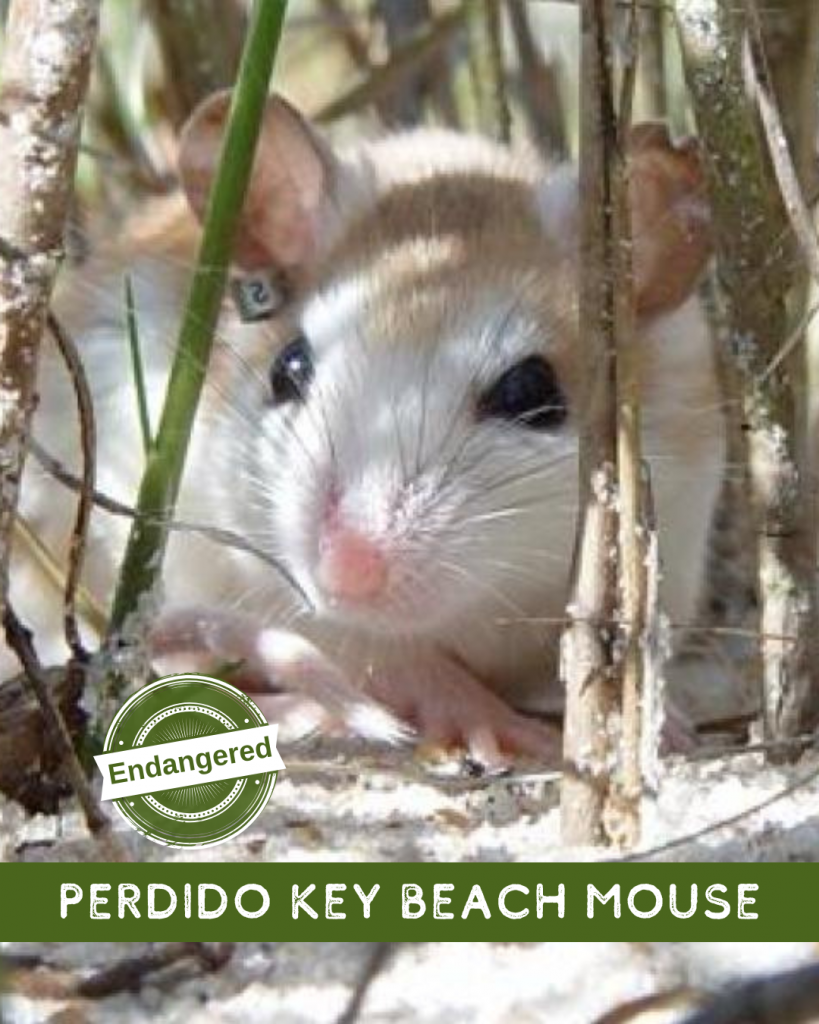

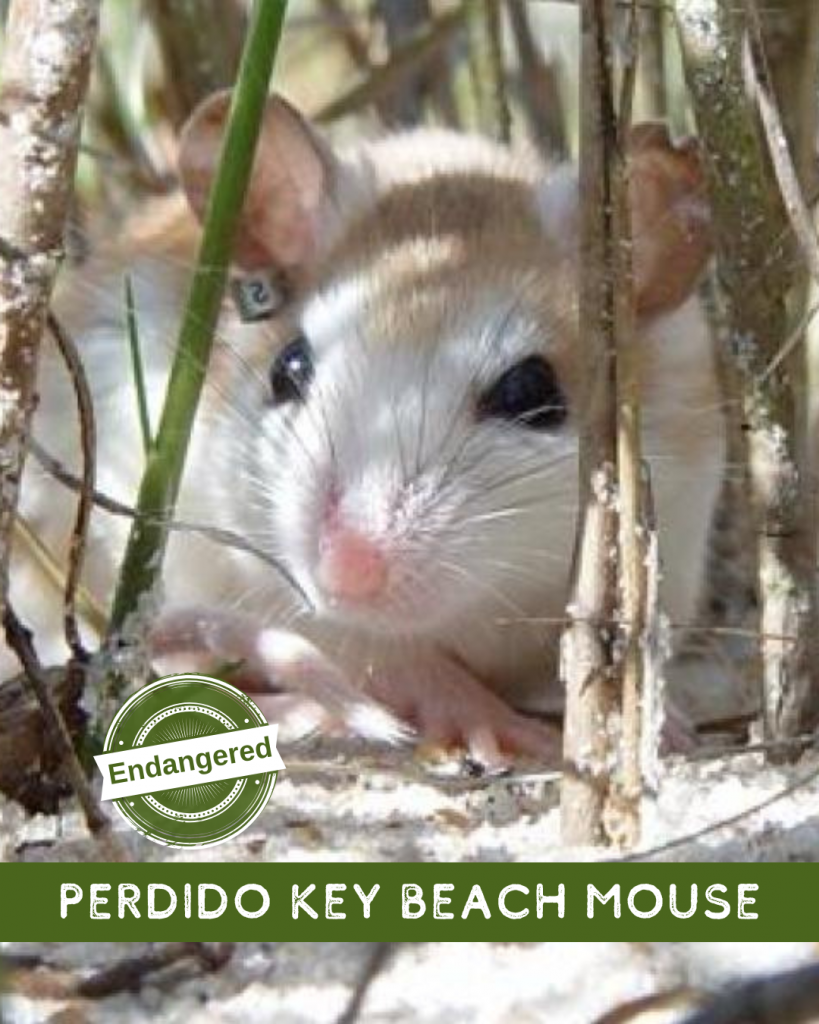

The Perdido Key beach mouse is a nocturnal rodent and a vital contributor to coastal biodiversity. It can fit in the palm of a hand, with a maximum length of 3.3 inches. While its size is small, its impact is mighty. By foraging for seeds and storing them underground, the Perdido Key beach mouse helps sea oat seeds take root and thrive within the coastal dune ecosystem. Thanks to the mouse’s efforts, these plants spread, sprout, and stabilize the dunes, creating a rich and resilient habitat. For this beach mouse, Perdido Key State Park is home. Threatened by habitat fragmentation and other factors, it has been recognized under the Endangered Species Act since 1985. To protect this species, you can stay off the dunes and avoid stepping on plants. Information from Florida State Parks and the National Park Service. Photo by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. #KnowYourFlorida #PerdidoKey #BiodiversityInstitute #ThompsonEarthSystemsInstitute #BeachMouse

If you are fortunate enough to spot a Schaus’ Swallowtail Butterfly, make sure to enjoy it from a distance! This rare species, endemic to South Florida, was one of the first insects listed as endangered in the United States due to threats from collection, habitat loss, and pesticide use. The remaining population resides on islands in Biscayne National Park and in Key Largo. The Schaus’ Swallowtail Butterfly plays an important role in Florida’s biodiversity. Interestingly, the species benefits from hurricanes. The caterpillars feed on torchwood and wild lime, which produce fresh shoots after storms and act as a food source. The butterflies, caterpillars, and host plants thrive in dense forest understories with limited light. Working with the University of Florida, the Florida Museum of Natural History, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park Service has performed several conservation efforts. Population surveys, laboratory rearing, supplemental release, and habitat advancements have led to an increase in their population in recent years. Information from the National Park Service and the Florida Museum of Natural History. Large photo by Isaac Lord via iNaturalist (CC-BY-NC 4.0). Small photo by Daniel Rivera via iNaturalist (CC-BY-NC 4.0). #KnowYourFlorida #Endangered #BiodiversityInstitute #ThompsonEarthSystemsInstitute #SchausSwallowtailButterfly

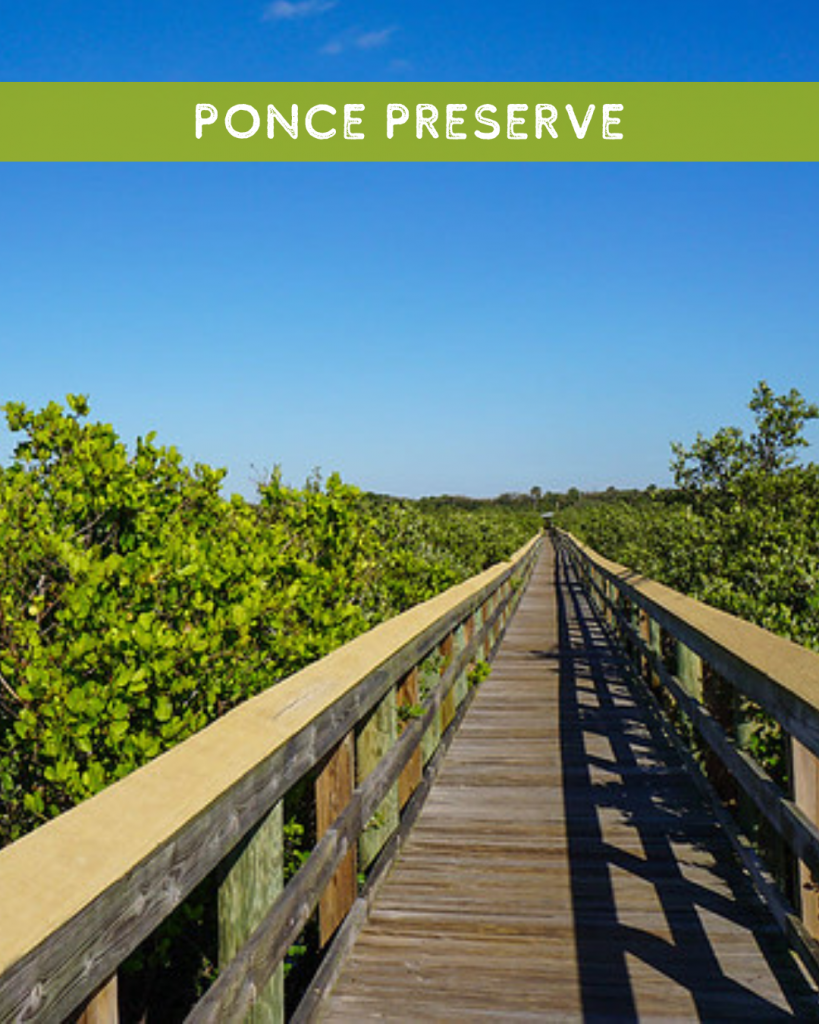

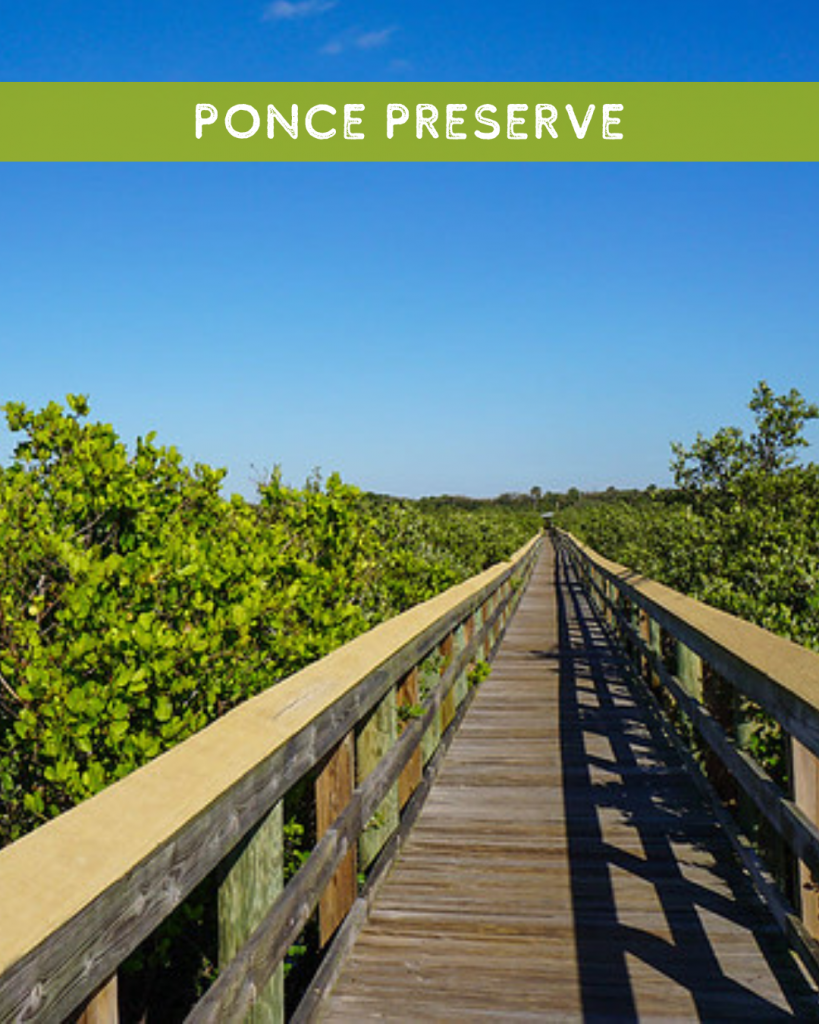

As the largest park in Florida’s Ponce Inlet, Ponce Preserve spans forty-one acres of rich ecological diversity. One of its most remarkable features is the thriving mangrove swamp, home to all three of the true mangrove species found in Florida: black, red, and white. Each species plays a unique role in the ecosystem, coexisting through a process called niche partitioning, where they adapt to different zones of salinity, elevation, and tidal flow. These mangroves support a vibrant web of life—from juvenile fish and crustaceans to nesting birds and pollinators—serving as a living classroom of coastal biodiversity. Visitors to Ponce Preserve can choose between two distinct trails. The boardwalk path, a flat and accessible route that winds through the mangrove swamp, offers close-up views of the dynamic habitat. The inland trail, a more adventurous hike through rolling coastal dunes, allows for encounters with gopher tortoises, dune sunflowers, and prickly pear cactus, among other native species. Whether you’re a nature enthusiast or a casual explorer, Ponce Preserve invites you to experience Florida’s coastal biodiversity in full bloom. Information from Florida Hikes, the Riverside Conservancy, the Florida Museum, and Ponce Inlet Facilities. Image from Florida Hikes. #KnowYourFlorida #PoncePreserve #BiodiversityInstitute #ThompsonEarthSystemsInstitute #MangroveResearch

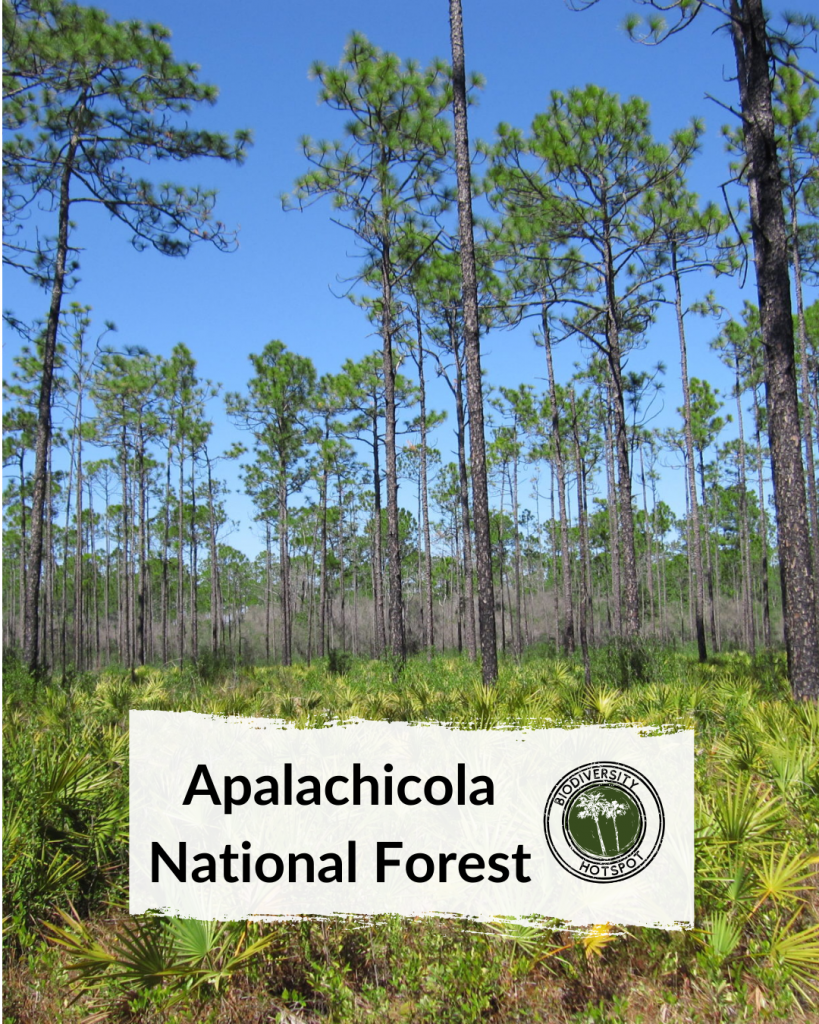

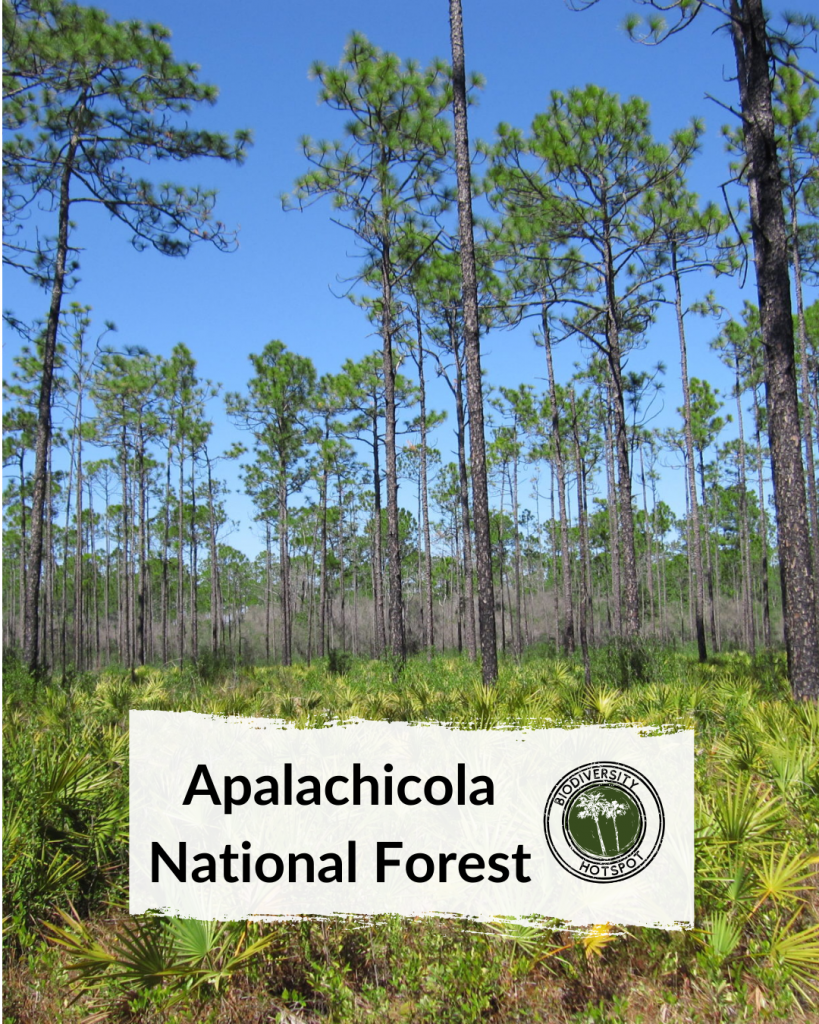

Since 1932, the Apalachicola National Forest has safeguarded one of the world’s most distinctive ecosystems. Established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, it is both Florida’s youngest and largest national forest, spanning 567,742 acres. Today, the U.S. Forest Service actively manages the landscape to keep it healthy and resilient. Visitors may see prescribed burns, invasive species removal, habitat restoration, selective timber harvests, or reseeding projects that support a thriving understory. Wildlife monitoring is also central to this work. The forest shelters threatened species such as the gopher tortoise, Florida black bear, and Florida scrub-jay, as well as endangered species like the red-cockaded woodpecker and the Florida sand skink. This biodiversity hotspot stems from a remarkable range of natural communities, from cypress strands and wet savannas to North Florida flatwoods and sandhills. In the east, sinkholes punctuate hillsides shaded by deciduous forest. The savannas dazzle with pitcher plants, ground orchids, Pinguiculas, and wiregrass gentians, while even a drive down State Road 65 offers roadside wildflowers unique to the region. Information from the Florida Native Plant Society, Biology Online, National Park Service, the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, and the US Forest Service. Photo from the Everglades Law Center. #KnowYourFlorida #ApalachicolaNationalForest #BiodiversityInstitute #ThompsonEarthSystemsInstitute #BiodiversityHotspot

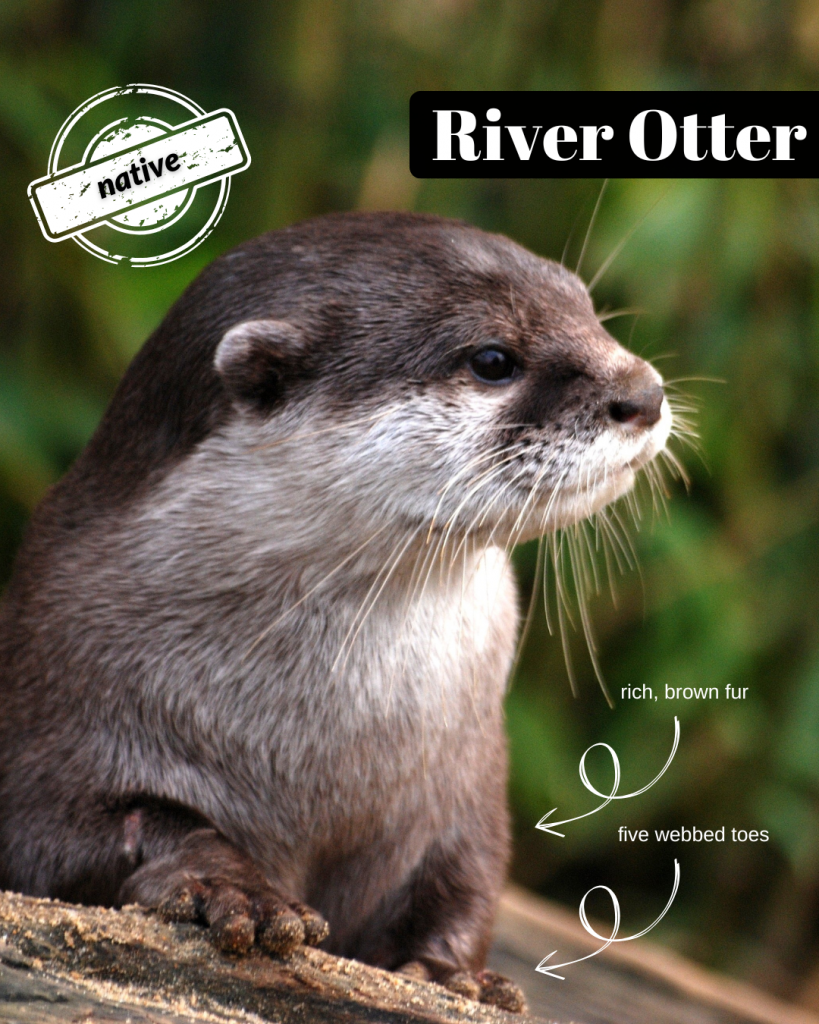

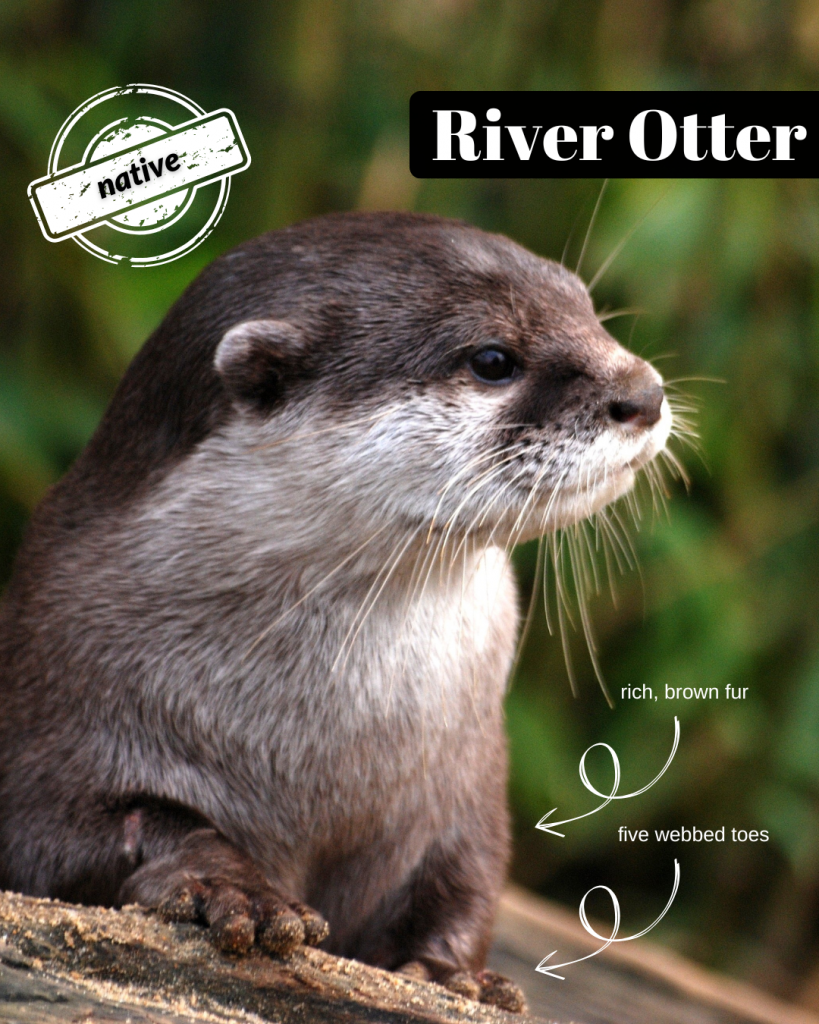

Native to Florida, the river otter prefers to live in the freshwater rivers, creeks, lakes, ponds, and swamps of peninsular Florida. They live in burrows that they dig on the banks of these water bodies, usually under tree roots. Or, they may even remodel a beaver’s burrow instead. River otters are water-loving, socially friendly semi-aquatic mammals and can often be found playing alone or with others. Groups typically consist of a female and her young. The river otter is adapted for both land and water. Their strong, flattened tail and their webbed toes help them glide swiftly through the water after their prey, which includes fish and crayfish. River otters are considered a species of least concern but still face threats from habitat loss and pollution. Making sustainable choices such as limiting the use of chemical fertilizers, and properly disposing of pet waste will increase the quality of the water the otters live in, and help to keep their population healthy. Information from Florida Museum of Natural History, Florida State University, River Otter Ecology Project, and Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Image from Canva Pro. #Florida #KnowYourFlorida #RiverOtters #FloridaNature #Mammals

Swamp for the Springs Videos (@UFEarthSystems)

Threats of the Springs / Why Florida Springs

Abigail Davis, UF ’27

Abigail Davis, UF ’27