New fossils from Eocene deposits of Panama on the Azuero peninsula (at arrow) are revealing that ~50 Million years ago, when North and South America were still separate continents, there was chain of islands between the two that hosted tropical rainforests.

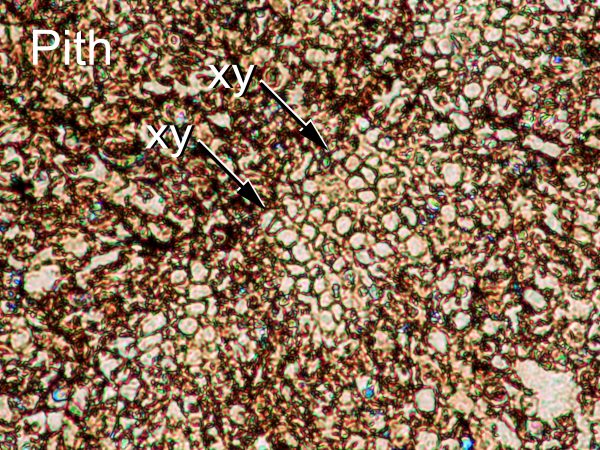

The fossils are fruits and woods are preserved in rocks formed from sediment deposited in a shallow marine setting roughly 50 million years ago. They are beautifully preserved. The cell walls of the plants were replaced by minerals, preserving exceptional detail that you just don’t get to see on a regular basis in vertebrate paleontology (because animals don’t have cell walls). To study the fossils, we use a saw to cut the rocks open, then we use a weak acid to dissolve the rock matrix away from the fossil, and finally we use an old technique to make a thin peel of the fossil that can be mounted on a slide and photographed!

Research using these fossils is providing an emerging picture of how the rainforests of Central America have changed over millions of years, and we can use that information to help us understand how the forests will change in the future. One pattern that we have already noticed is that there are many species that occur as fossils in Panama, but the living relatives are only found in the old world tropics of Africa and Asia. Here is one example.

This fossil species is closely related to modern Dracontomelon species, which are found in southern China and Southeast Asia. Dracontomelon is in the family Anacardiaceae, along with Cashews, Mangos, Poison Ivy, and the popular ornamental “Smoke tree”.

Dracontomelon trees are large rainforest trees, and according to the Plant List there are 9 species. The fruits are greenish and are used to make candy and in Asia, the brownish colored pit of the fruit is sometimes called “human-face” because of the shape of the valves where the germinating seeds burst through the pit. The pit is what is preserved here as a fossil. It is thick-walled and contains five seeds and five air-spaces, seen in cross section above. Below is a photo from Flickr of the pits of a modern species.

So why were lineages like Dracontomelon extirpated from the New World Tropics? We don’t have an answer yet, but researchers have already addressed a similar question regarding temperate forests. There are many types (families, genera) of trees that are much more species-rich in Asia than in North America; and there are several that occur only in Asia today, but we know from fossil evidence that they were present in North America during the early Cenozoic. This asymmetry in temperate forest diversity between the two continents was generated in large part by the effects of climate change during the late Cenozoic and into the recent ice ages. Asia has more land area and more landscape diversity than North America, and so as regional climates changed, plants had more opportunity to track suitable habitat in Asia than in North America and therefore the effects of climate change on biodiversity were not as severe in Asia as in North America.

What made Asia a safer place back then seems to be the extent and connectivity of potential habitats. As modern climate change and land use change shrinks and moves suitable habitat, It becomes even more important to designate large areas where rainforests can remain intact or be created so that species can track suitable habitat.

References

Herrera, F., Manchester, S. R., & Jaramillo, C. (2012). Permineralized fruits from the late Eocene of Panama give clues of the composition of forests established early in the uplift of Central America. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 175, 10-24.

Qian, H., & Ricklefs, R. E. (2000). Large-scale processes and the Asian bias in species diversity of temperate plants. Nature, 407(6801), 180-182.

0 responses to “Plant fossils from the Azuero Peninsula: Dracontomelon”