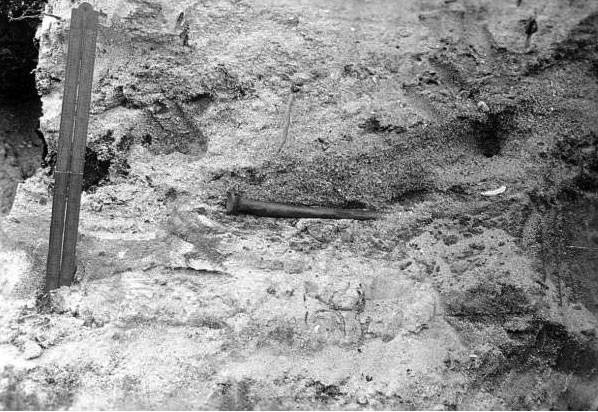

Vero Canal Site, Stratum 2

University of Florida Vertebrate Fossil Locality IR005

Location

The site is located within the City of Vero Beach, Indian River County, Florida, to the southeast of the municipal airport. 27.65º N; 80.40º W.

Age

- Late Pleistocene Epoch; late Rancholabrean land mammal age

- 20,000-12,000 years ago

Basis of Age

Radiocarbon dating and vertebrate biochronology are consistent with a very late Pleistocene age.

Geology

The Vero Canal Site, Stratum 2 of Sellards (1916) is a series of thin layers of sand and silt. Stratum 2 is overlain by Stratum 3, which is primarily a Holocene deposit. In places, a small modern creek had eroded through Stratum 3 into Stratum 2, and the modern creek deposit contained a mixture of fossils and artifacts from both strata.

Depositional Environment

Primarily thought to be a stream and/or pond deposit. In addition to sedimentary structures and grain size, this is supported by abundant remains of the aquatic salamanders Siren lacertina and Amphiuma means, the water snake Nerodia sp., and the muskrat Neofiber alleni. Overall, freshwater and swamp-dwelling species make up a large percentage of the vertebrate fauna of Stratum 2 (Weigel, 1962). However, the lower layers of sand in Stratum 2 were probably deposited by wind under a drier climatic regime during a glacial interval of global climate (Hemmings et al., 2014).

Fossils

Excavation History and Methods

The Vero Canal Site was discovered over 100 years ago following the construction of a drainage canal by the Indian River Farms Company. The canal cut through a bone-bearing deposit that extended for over 300 m, although it is only a few meters thick. In 1913, F. C. Gifford found the first fossils in the bank of the canal (Sellards, 1916). He turned them over to Isaac M. Weills, who began to collect additional specimens with Frank Ayers and other local residents. Fossils were found on the banks of both sides of the canal, and both east and west of the railroad track crossing the canal.

Weills reported the discovery to Florida state geologist Elias H. Sellards, who visited the location with his assistant Herman Gunter. Collecting efforts increased significantly after Ayers found portions of a human skeleton in Stratum 2 in October 1915. At the time, these were the first well documented human remains from the Pleistocene of North America. Sellards quickly reported this important discovery in several scientific publications in 1916, and held an on-site conference with leading archaeologists of the day. Despite Sellards’ field documentation and an early geochemical analysis that showed that the human bones from Vero were mineralized to the same degree as those of Pleistocene megafauna, most of the archaeologists of the time did not believe the age of the human bones was Pleistocene. New geochemical analyses (MacFadden et al., 2012) and detailed excavations by a modern archaeological field crew (Hemmings et al., 2014), have demonstrated that Sellards’ claims of finding the first solid evidence of humans in the Pleistocene of the New World and their co-existence with extinct megafauna were correct.

This first excavation phase at the Vero Canal Site by Ayers, Weills, and Sellards lasted until 1918, although the occasional specimen turned up on the eroding canal bank from time to time. Sellards left Florida for Texas in 1919, and the attentions of the Florida Geological Survey (FGS) turned elsewhere (probably somewhat burned by the unfavorable reception Sellards had received from the scientific community). Some of the Vero specimens in the FGS collection were turned over to the Smithsonian for safe keeping upon Sellards’ departure, although the FGS retained two of the early gems, the holotype skull of Tapirus veroensis (Sellards, 1918) and the holotype skull of Canis ayersi (now Canis dirus; Sellards, 1916). Weills’ widow donated his entire fossil collection to the FGS in 1927; it included specimens from many locations in the Vero area, but a large number were from the Canal Site. About 350 total identifiable specimens were collected during this phase.

The next significant collection at the Vero Canal Site was conducted by UF graduate student Robert Weigel in 1956 and 1957 (Weigel, 1962). He excavated on the north side of the canal over an area of 9 by 9 feet, divided into 3 x 3 foot squares. Matrix from both Stratum 2 and sStratum 3 was removed in 6 inch levels and washed through 1/8 inch screens (Weigel, 1962). The purpose of this dig was to use screening to recover small vertebrate remains and use them to interpret the paleoecology of the site. Weigel’s efforts to recover a diverse microfauna were very successful, with a recovery of about 1100 identifiable specimens. Weigel’s excavation did not recover any human fossils in Stratum 2, but he did find some pieces of worked flint. An additional 122 identifiable specimens were collected in the 1950s from Stratum 2 by Herbert Winters of the FGS.

Scientific excavations at the Vero Canal Site did not resume until 2014, when a crew of from Mercyhurst Archaeological Institute lead by C. Andrew Hemmings conducted a very controlled, archaeological-style operation on the south side of the canal (Hemmings et al., 2014). They located an area close to Sellards’ original area that coring and ground-penetrating radar revealed preserved undisturbed strata representing Sellards’ strata 2 and 3. Radiocarbon dating of ancient soil layers (paleosols) revealed ages of about 8, 12, and 19 thousand years before present in stratigraphic superposition. Thus the deposits span the Holocene-Pleistocene boundary and then extend to the Wisconsin glacial interval. The area excavated by the 2014 Mercyhurst field season approached the Holocene-Pleistocene boundary. On-going excavations by this group in 2015 will proceed deeper into the Pleistocene.

No access, for collecting or excavating, is allowed at the Vero Canal Site without proper authorization of the City of Vero Beach.

Discussion

The Vero fossil locality is the first New World discovery of human bones and artifacts in association with extinct Pleistocene vertebrates. As such it will always be a scientifically significant locality. But from a purely paleontological perspective, the site was soon surpassed by the Melbourne and Seminole Field localities, which both produced greater numbers of specimens and many of higher quality. Much of the early taxonomic work done on the Vero fossil vertebrates was not of very high quality, resulting in the naming of many invalid species, especially by Hay (1916, 1917) and Shufeldt (1917), but also by Sellards (1916) to a lesser degree.

The vertebrate fauna found at Stratum 2 includes almost all of the known extinct late Pleistocene megafauna that inhabited Florida. Examples are the large extinct tortoise Hesperotestudo, three ground sloths (Megalonyx, Paramylodon, and Eremotherium), seven ungulates, and four carnivores. With the exceptions of the fine skulls of Canis dirus and Tapirus veroensis (Figure 3) and two mandibles of Holmesina septentrionalis, most of these are known from a relatively small number of isolated teeth and/or broken bones. For this reason, modern research has tended to focus on the small-sized component of the fauna, such as the bats (Morgan, 1985) and rodents (Wilkins, 1984; Ruez, 2000).

The faunal list provided here is only for taxa confirmed to originate from stratum 2 and thus of Pleistocene age. It was derived from that in Weigel (1962), corrected using subsequent research papers and confirmed with specimens housed at the Florida Museum of Natural History. The list on the Paleobiology Database is a combination of taxa from strata 2 and 3. This means it is mix of Holocene and late Pleistocene species.

The Old Vero Ice Age Sites Committee is a local organization that supports the on-going excavation and research of the Vero Canal Site. Visit their website to volunteer, to arrange a tour of the site during field season, and view a schedule of lectures and other events.

Sources

- Original Author: Richard C. Hulbert Jr.

- Original Completion Date: March 11, 2015

- Editor(s) Name(s): Natali Valdes

- Last Upated: June 16, 2015

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number CSBR 1203222, Jonathan Bloch, Principal Investigator. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Copyright © Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida