The Calusa Indians were one of the most prolific Native American groups in North America. When the Spanish visited southwest Florida in the 1500s, they encountered the highly sophisticated Calusa who developed a complex political economy based on not agriculture like other groups at the time – but rich estuarine resources like fish and shellfish.

The Calusa, and other groups in southern Florida like the Tequesta and their ancestors engineered substantial canals both within island settlements and between their towns and interior waterways. The paths of these canals are clearly visible on aerial photographs collected prior to modern development and are described in detail by explorers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For example, in 1895 and 1896, when Frank Hamilton Cushing visited the Pineland Site Complex, parts of the Pine Island Canal were still 30 feet wide and 6 feet deep, and today they are nearly undetectable to the naked eye.

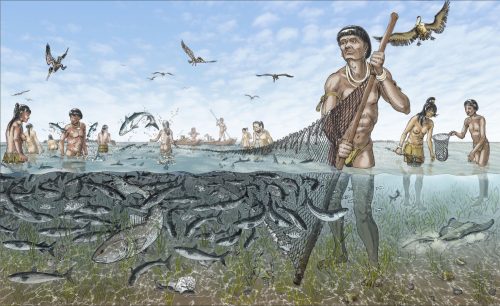

The aquatic engineering skills that supported the political economy of the Calusa not only improved living conditions and enhanced cultural connections between groups but also allowed people to thrive during regional environmental stressors such as fluctuations in sea level, drought, and resource depression. One of the ways people may have been able to intensify their food production during uncertain times was by means of large-scale fishing weirs, dams, traps, and holding pens. Linear keys still visible today in the greater Charlotte Harbor estuarine system that was the heartland of the Calusa Indians represent the remnants of these elaborate large-scale fishing facilities.

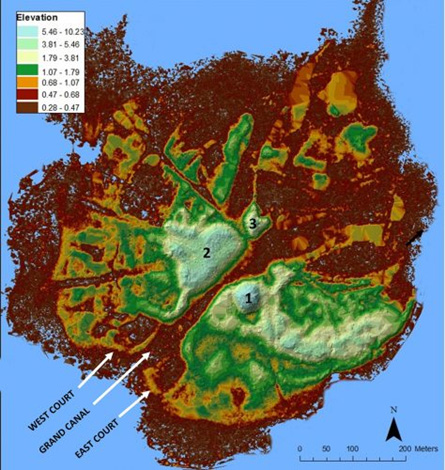

Archaeologists use advanced imaging technologies such as “remote sensing” to study and map large coastal shell mound sites, including those in southern Florida that can span several football fields in size. Their geographical sprawl on the landscape makes traditional archaeological surveys by foot time-consuming and challenging. However, with remote sensing techniques utilizing aerial and satellite-based sensors, researchers can efficiently capture high-resolution imagery and elevation data over large areas. These tools enable the creation of detailed maps that reveal the extent and spatial organization of shell mound sites, as well as associated features like ancient pathways, canals, and living spaces.

Read more about the research carried out by Drs. William Marquardt (FM Curator Emeritus), Victor Thompson (University of Georgia), and Karen Walker (FM retired): Sophisticatedly engineered ‘watercourts’ stored live fish, fueling Florida’s Calusa kingdom

In addition to the work carried out on Mound Key Archaeological State Park with past Florida Museum faculty and staff, Jen Green (South Florida Archaeology Collections Manager, Florida Museum) and Daniel Spikowski (Calusa Land Trust) have employed remote sensing technologies on sites across southwest Florida on Pine Island.

Green and Spikowski participated in a comprehensive drone-based mapping and imagery course instructed by Dr. Jim Blanchard of the Unmanned Autonomous Systems Academy (UASA) and Johns Hopkins University. They joined other professionals from across the country to learn the implementation of aerial mapping using drones in a broad array of contexts including from the land and by boat, two important skills for mapping coastal archaeological sites. Their work has provided comprehensive aerial maps of the Randell Research Center – a program of the Florida Museum of Natural History and public education facility, and of Calusa Island which is managed by the Calusa Land Trust on the northern end of Pine Island.

Read more about using drones as archaeological research and land management tools at the Randell Research Center and on Calusa Island: It’s a Bird, It’s a Plane, It’s a…Drone!

In the wake of Hurricane Ian which made landfall on the Gulf Coast of Florida on September 28, 2022, a series of actions were taken to document storm damage and impacts to archaeological sites in southwest Florida including at the Randell Research Center, Mound House, Calusa Island, and Mound Key Archaeological State Park.

Florida Museum Curators Drs. Michelle LeFebvre (South Florida Archaeology and Ethnography) and Nick Gauthier (Artificial Intelligence) teamed up with Dr. Isabelle Holland-Lulewicz (Penn State), and the Florida Public Archaeology Network to support local site managers across these four key Calusa heritage sites impacted by the storm under a National Science Foundation RAPID grant (Award #2304807).

Read more about their efforts: Archaeologists awarded NSF grant to survey Florida cultural heritage sites damaged by Hurricane Ian