Shark attacks were unusually low for the second year running, with 64 unprovoked bites in 2019, according to the University of Florida’s International Shark Attack File. The total was roughly in line with 2018’s 62 bites and about 22% lower than the most recent five-year average of 82 incidents a year.

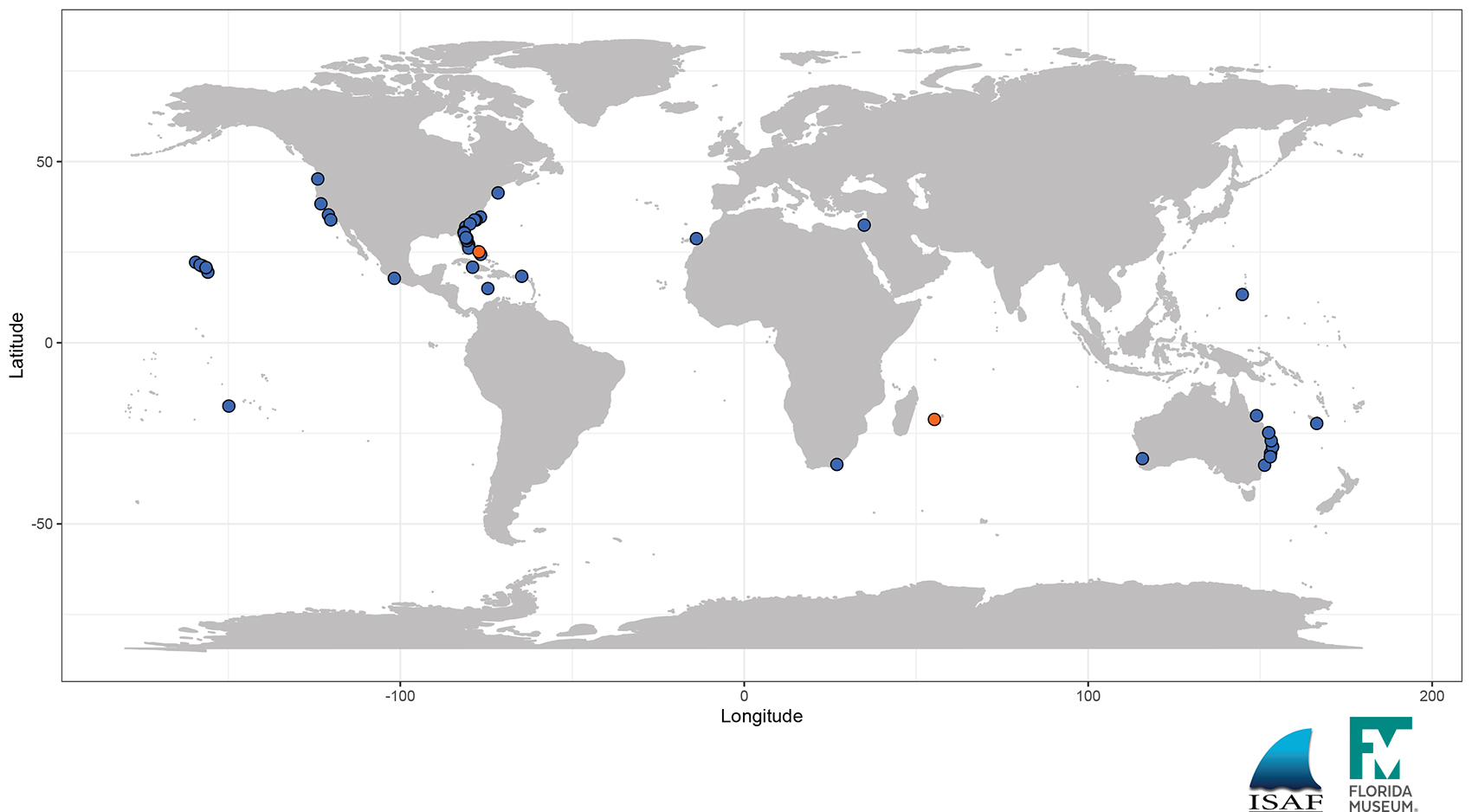

Two of the bites, one in Reunion and one in the Bahamas, were fatal, a drop from the average of four deaths from unprovoked attacks a year. Consistent with long-term trends, the U.S. led the world in shark attacks with 41 bites, an uptick from 32 the previous year, but significantly lower than the nation’s five-year average of 61 bites annually. Attacks were mostly concentrated in the Southeast with 21 in Florida.

While the number of shark attacks can vary from year to year, Gavin Naylor, director of the Florida Museum of Natural History’s shark research program, said the recent decline may reflect changes in the migration patterns of blacktip sharks, the species most often implicated in Florida bites.

“We’ve had back-to-back years with unusual decreases in shark attacks, and we know that people aren’t spending less time in the water,” Naylor said. “This suggests sharks aren’t frequenting the same places they have in the past. But it’s too early to say this is the new normal.”

The ISAF investigates all human-shark interactions, but focuses its annual report on unprovoked attacks, which are initiated by a shark in its natural habitat with no human provocation.

Florida Museum image by John Denton

Global shark attacks by the numbers

Australia had the second-most shark attacks globally with 11, a decrease from the country’s most recent five-year average of 16 bites annually. The Bahamas followed, with two attacks.

Single bites occurred in the Canary Islands, the Caribbean Islands, Cuba, French Polynesia, Guam, Israel, Mexico, New Caledonia and South Africa, once a hotspot for shark attacks.

“The news coming out of South Africa is that they’re not seeing as many sharks,” said Tyler Bowling, manager of the ISAF. “White sharks have been moving out of some areas as pods of orcas move in, and there are reports that sharks are disappearing along the whole Cape.”

Florida tops shark attack leaderboard

Florida has led the world in number of shark attacks for decades, and 2019 was no exception. The state’s 21 unprovoked bites represented an increase from 16 the previous year and accounted for 33% of the global total. But attacks were about 34% lower than the region’s five-year average of 32 incidents a year.

Volusia County had the most shark bites with nine, followed by Duval, 5, and Brevard, 2, with single attacks in Broward, Martin, Nassau, Palm Beach and St. Johns counties.

Illustration by Lindsay Gutteridge

Hawaii saw a small spike in attacks, with nine in 2019 compared with three the previous year. California and North Carolina had three shark attacks each. Single bites occurred in Georgia, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina and the Virgin Islands.

Massachusetts, where two great white sharks attacked in 2018 with one fatality, had no incidents in 2019. New York, where two bites occurred within minutes of one another in 2018, also had no attacks.

Year of the cookiecutter

In a historic first, the elusive, foot-long cookiecutter shark was responsible for three of 2019’s attacks. All three bites were on long-distance swimmers training in Hawaii’s Kaiwi Channel at night.

The ISAF’s more-than 6,400 records only contain two other accounts of unprovoked cookiecutter bites on live humans: one in 2009 in Hawaii’s Alenuihaha Channel and one in 2017 in North Queensland, Australia.

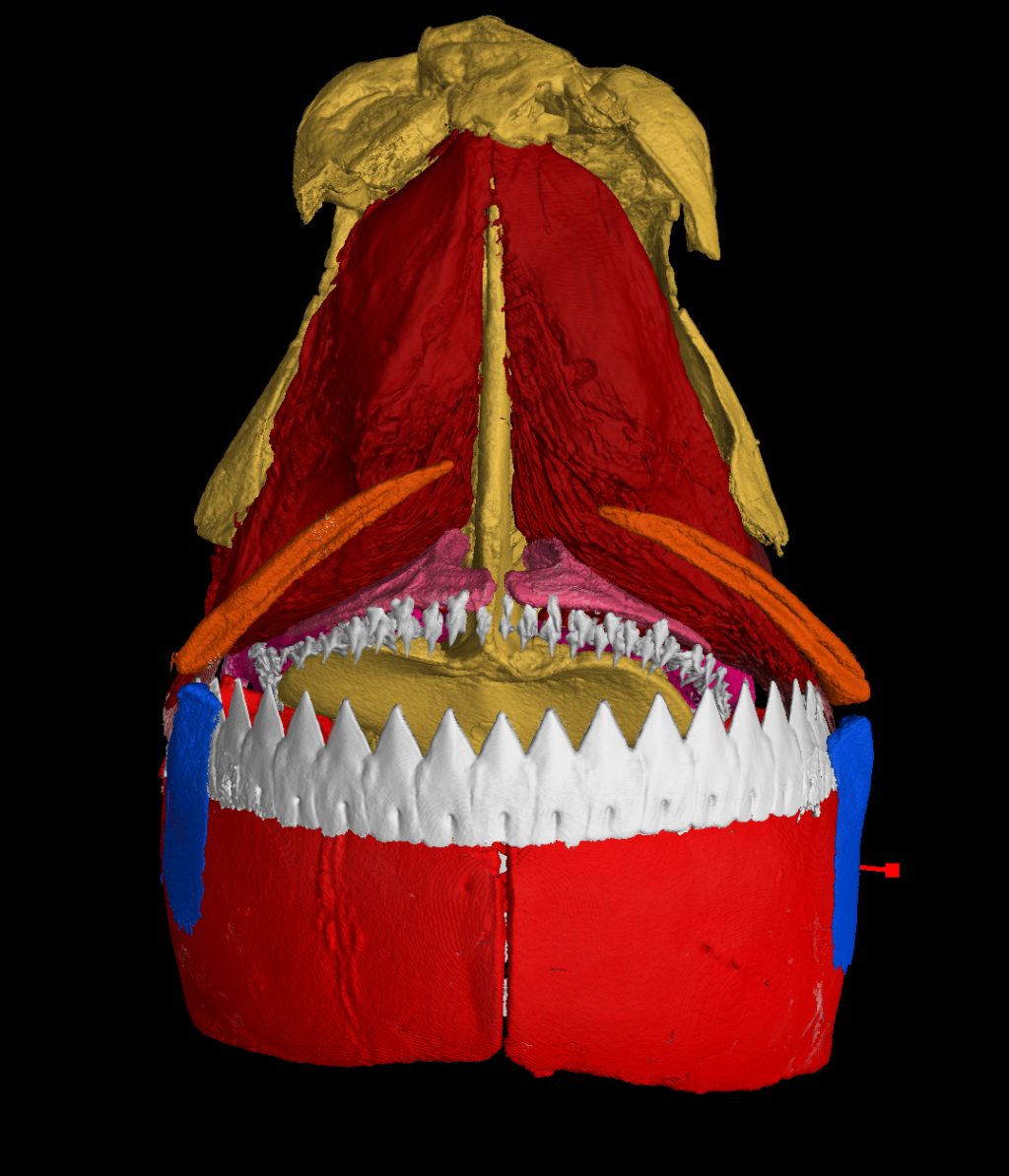

The snub-nosed, cigar-shaped shark, often considered a parasite, attaches to its prey with rubbery lips and uses its robust muscles and circular jaw to extract a plug of flesh – “acting like a toilet plunger with a blade in it,” Naylor said. It leaves distinct, craterlike wounds on a wide range of marine life, including tuna, seals, dolphins and even great white sharks, 10 times the cookiecutter’s size.

Not much is known about the cookiecutter shark, Naylor said.

“They’re quite mysterious animals,” he said. “While they’re found all over the world, we don’t know how many of them there are, or how exactly they create this seemingly perfect circle. They can look pretty pathetic, like a lazy sausage, but they can do a lot of damage.”

Reports of sharks trailing fishing boats increase

Anglers on the East Coast are increasingly reporting dramatic masses of sharks trailing fishing boats and a rise in depredation – sharks eating fish on the line. But Naylor and Bowling cautioned against interpreting the surge in shark sightings as a sign that shark populations have recovered after decades of decline.

“Shark aggregations are highly localized,” Naylor said. “We haven’t yet seen census data that show shark numbers are bouncing back.”

Bowling said anglers have also noted a decline in fish, which could mean hungry sharks are training their sights on fishing boats as an easy means of snagging a meal.

“If their resources are thin, they’re going to go to places that are more reliable, and if that means fishing boats, that’s where they’re going to go,” Naylor said. “That exacerbates problems for fishermen.”

As sharks approach boats, they are drawn into close quarters with humans and may unintentionally bite a person while in pursuit of fish, Bowling said. Several of 2019’s bite victims reported that sharks approached as boat captains revved their engines, he said.

“They associate that noise with food,” Bowling said.

While the chances of being bitten by a shark are minimal, the ISAF offers recommendations for how to lower the risk of a shark attack or fend off an attacking shark.

Sources: Gavin Naylor, gnaylor@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-1954;

Tyler Bowling, tbowling2@ufl.edu, 352-273-1949