Alligator mississippiensis

Quick Facts

Common Name: American alligator

The American alligator is an incredibly adaptable crocodylian, has lived for millions of years with little morphologic change, and has survived numerous instances of climate and sea level change relatively unaffected.

Alligators are polyphyodont and can easily produce hundreds or thousands of teeth during their lifespan which commonly become fossilized.

Age Range

- Early Pliocene to latest Pleistocene Epoch; Hemphillian through Rancholabrean land mammal ages

- About 5 million to 11,000 years ago

- cf. Alligator mississippiensis: middle to late Miocene Epoch; Clarendonian to early Hemphillian land mammal ages

- cf. Alligator mississippiensis: 12 to 6 million years ago

Scientific Name and Classification

Alligator mississippiensis Daudin, 1802

Source of Species Name: named for the Mississippi River region of North America, which is part of the modern range of the species.

Classification: Reptilia, Archosauria, Crocodylomorpha, Crocodylia, Alligatoridae, Alligatorinae

Alternate Scientific Names: Crocodilus mississippiensis, Crocodilus luicus, Crocodilus cuvieri, Alligator luicus, Alligator helois, Champsa lucia, and possibly Alligator mefferdi and Alligator thomsoni

Overall Geographic Range

The modern American alligator ranges throughout the southeastern United States, and most definitive fossil localities for this species also exist in the same region, from Texas to Florida (Preston, 1979; Brochu, 1999; Meylan et al., 2001). In warmer climatic periods such as the middle–late Miocene, the American alligator (or its close relatives/possible synonyms Alligator thomsoni and Alligator mefferdi) ranged farther north and west than today (Mook, 1923, 1946).

Florida Fossil Occurrences

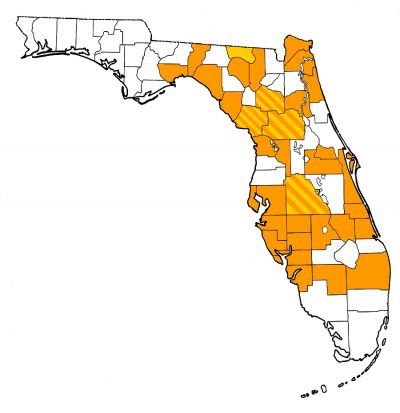

Florida fossil sites with Alligator mississippiensis and cf. Alligator mississippiensis:

Discussion

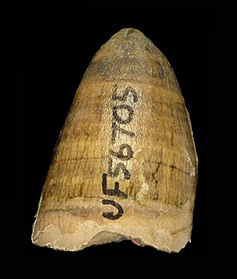

Fossils of the American alligator are found throughout much of Florida (Fig. 1). Not surprisingly, given the species’ preferred habitats today (e.g., swamps, lakes, and rivers), its fossils are most common at sites formed in fresh-water habitats and are typically found together with species having similar ecologic preferences, such as aquatic turtles, wading birds and ducks, and frogs. Alligators will move across land from one body of water to another, so their fossils do end up in fossil deposits not associated with water, such as dry sinkholes and caves, but typically not in large numbers. Alligators also are not very salt tolerant, especially compared to crocodiles, so are rare or absent in nearshore marine deposits. The most common fossils found are isolated teeth and osteoderms (Fig. 2). Alligators are both homodont and polyphyodont (For more discussion and comparisons of fossil crocodylian teeth and osteoderms from Florida, see species accounts of Alligator olseni and Thecochampsa americana).

Complete skulls are very important for species diagnosis within the genus Alligator, and as such are highly valued fossil finds no matter their age or origin. But these are relatively rare, as the individual bones tend to separate easily from each other after death, so isolated skull bones are found more commonly (Fig. 3). The mandible consists of separate bones: the tooth-bearing dentary (Fig. 4), the splenial which inserts along the ventral margin of the medial side of the dentary, and three other bones found at the posterior end of the mandible: the angular, surangular, and articular.

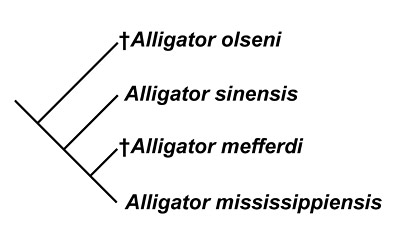

Taxonomic issues plague the systematics of the genus Alligator, largely due to the high degree of similarity between currently recognized fossil species and a wide degree of intraspecific morphological variation in both extant and extinct species. The diagram in Figure 5 shows the results of one recent analysis on the evolutionary relationships of fossil and modern species in the family Alligatoridae. In this analysis, the early Miocene Alligator olseni of Florida falls outside a group that includes the two living species, the Chinese alligator, Alligator sinensis and the American alligator. The middle Miocene species Alligator mefferdi came out as the closest relative of Alligator mississippiensis. Alligator mefferdi has a shorter, blunter snout and a somewhat greater degree of cranial ornamentation around the orbits than most modern and Pleistocene Alligator mississippiensis. However, the high degree of intraspecific morphological variation in American alligators for these features could account for the morphology seen in the middle Miocene species, thus making it a synonym of Alligator mississippiensis (Malone, 1979). Brochu (1999) and Snyder (2007) favored recognizing Alligator mefferdi as a valid species distinct from Alligator mississippiensis based on these characters of the skull.

A conservative approach is taken towards classification of fossil specimens of Alligator in this account. There are few Barstovian (early middle Miocene) records of Alligator in Florida, and the known fossils are not diagnostic at the species level. Snyder (2007) described relatively complete specimens of Alligator from the late Miocene (Hemphillian) Moss Acres Racetrack locality in Marion County, Florida, but could not make a definitive assignment to Alligator mefferdi due to a lack of preserved features. No Alligator specimens from any Florida locality have thus far been shown to exhibit the diagnostic features of Alligator mefferdi. Assignment of middle and late Miocene Florida specimens of Alligator to an extinct species is discouraged until the requisite diagnostic characteristics are observed. An equally valid argument can also be made that they represent early members of Alligator mississippiensis.

In an unpublished thesis, Stout (2009) suggested that a new species be named for Alligator from the early Pleistocene (Blancan) Haile 7C and 7G sites in Alachua County, Florida. But he never formally named this species or suggested diagnostic characters in sufficient detail. Observation and analyses of the same specimens and others from Haile 7C and 7G do not support his conclusion that a new species is apparent. Instead, the relatively complete Haile 7C and 7G specimens provide a more definitive lower chronologic boundary for the occurrence of Alligator mississippiensis in the Florida fossil record (extending it to the late Blancan, about 2 million years ago). These Haile 7C and 7G alligators appear to have attained quite large sizes at maturity, and Alligator mississippiensis may have reached lengths of up to seven meters during the Pleistocene, several meters longer than the largest modern American alligators (Meylan et al. 2001). The Haile 7C and 7G Alligator mississippiensis sample is also unique in that it includes individuals that were likely hatchlings at the time of death, and they exhibit a few characteristics allying them with modern alligators. The Haile 7C and 7G fossils provide a nearly unprecedented glimpse into a thriving American alligator population living nearly 2 million years ago in a large sinkhole lake (Morgan and Hulbert 1995; Hulbert et al., 2006; Hulbert, 2010).

American alligators are important to modern ecosystems, and act as keystone predators that are essential for keeping prey populations in check. In addition to their ecological importance, American alligators are also major components of certain economies that exploit them for their meat and skin. They are also crucial study subjects in a multitude of different scientific disciplines ranging from dentistry to immunology, and are utilized in various research projects. The significance of these reptiles across such a wide variety of topics is almost unmatched, and warrants their protection and conservation. American alligators have recovered from once being endangered, and their populations have exploded in certain areas of the Southeastern United States. This iconic reptile is also the beloved mascot for the University of Florida, and occupies a unique cultural niche in the fabric of Floridian society.

Alligator mississippiensis is one of the most widely-studied and well-known reptiles in the world, and yet it still offers a diverse array of research avenues for new scientists. The American alligator is an incredibly adaptive crocodylian, has lived for millions of years with little morphologic change, and has survived numerous instances of climate and sea level change relatively unaffected.

Sources

- Original Author(s): Evan T. Whiting

- Original Completion Date: September 8, 2013

- Editor(s) Name(s): Richard C. Hulbert Jr., Natali Valdes

- Last Updated On: February 25, 2015

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number CSBR 1203222, Jonathan Bloch, Principal Investigator. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Copyright © Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida