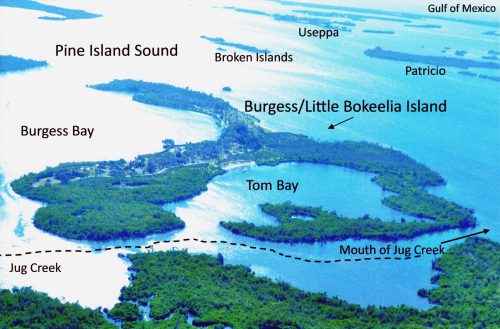

Burgess/Little Bokeelia Island rises just off northwestern Pine Island where Jug Creek enters the Sound. It has about 29 acres of uplands with ancient sand dunes topped by shallow, aboriginal shell mounds, in addition to acres of mangroves partially enclosing two bays, Burgess Bay and Tom Bay.

Its original name was Little Bokeelia Island. The word “Bokeelia” is from the Spanish word boquilla , meaning “little mouth,” referring to the mouth of Jug Creek, which borders the island.

In 1924 when Charles Frederick Burgess and his wife, Ida May Jackson, purchased Little Bokeelia Island, Dr. Burgess was already one of the most respected scientists in America. Burgess began his career as a professor of Applied Electrochemistry at the University of Wisconsin (UW). He achieved international recognition not only through his inventions and his business success, but through his presidency of the American Electrochemical Society. It was a position, he stated years later, that allowed him to rub shoulders with Thomas Alva Edison, Nikola Tesla, Edward Goodrich Acheson, E.F. Northrup, and more.

Burgess’s future wife, Ida May Jackson, was appointed a State Factory Inspector by the governor of Wisconsin, Robert M. LaFollette, a reformer who happened to have married the first female graduate of the UW law school. Ida May was described as a bright young woman with a good sense of humor. Burgess’s opinion of her was, “This is the first girl I ever met that I could look up to intellectually.” The Burgesses married in 1902 and had two children, Betty and Jack, whose playmates included a future famous author, Thornton Wilder.

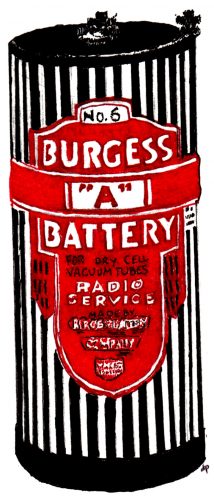

Working in the lab, Burgess received patents for a type of dry cell battery first used in small flashlights and telephones. Through his private research company as well as through his manufacturing company, he achieved success, opening several plants in the Midwest and in Canada, focusing on specialized products for military-industrial purposes during World War I. Other manufacturers of small products used his battery patents with his permission including the battery company that later became Ray-O-Vac. Burgess proved to be a very practical businessman, producing high quality products at the lowest possible cost. He recycled materials from old batteries and turned industrial and forest by-products into useful applications.

Burgess was the first to devise a convenient means for converting alternating current into direct current for small installations as in a car or a boat. Among his inventions were different types and sizes of dry-cell batteries; a process for purifying electrolytic iron; an electrochemical sterilizer used successfully in hospitals; a battery powered water sterilizer small enough for camping; an engraver for metal, glass, and wood; an electrical method for hardening heat-setting adhesives such as resins; the Micro-switch for which a division of Honeywell was named; the Burgess Multiple Outlet; acoustic insulating materials and tiles; and pulsation snubbers to reduce factory noises. He also developed the type of insulation used in Charles Lindbergh’s airplane, The Spirit of St. Louis.

In 1924 Burgess bought Little Bokeelia Island from his friend, De Witt Clinton Harris, a seasonal resident of Pineland, who was the owner of a typewriter factory in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin. Harris had built the Harris Cottage at Pineland on Brown’s Complex Mound 5, across from the Tarpon Lodge. He held several patents on various mechanisms for typewriters. (An original“Harris Visible” typewriter is on display in the RRC offices at the Ruby Gill House.)

In 1926 a severe hurricane destroyed all but a small cottage used for battery storage. Within two years a Spanish-style mansion was constructed to a design drawn by architect C. Sedgewick Moss of St. Petersburg. Burgess researched and installed a type of balsam-wool home insulation for his Florida home where it remained until Hurricane Charley in 2004, when it received a direct hit and was removed soaking wet. The subsequent renovation embraced modern materials while retaining the old Spanish-style charm with a tiled roof, courtyard, and arched breezeway.

In 1930 Burgess established his winter laboratory and office in one of three small buildings constructed on the highest elevation on the island. Two guest cottages were built in the Florida Cracker-style which includes covered porches and airy coolness at night. He hired a leader in American shortwave radio to set up a radio station on Burgess Isle using a wrecked sailboat mast as an antenna so that communication with the Burgess Battery Company in Wisconsin could be accomplished “without the annoying ring of a telephone,” said Burgess. The shortwave-radio Burgess Batteries were the same as those used by polar explorers in the 1930s, MacMillan, Byrd, and others, who were quoted in The National Geographic Magazine of October 1935 praising the batteries for their longevity.

The Burgess guest book recorded visits by Thomas Edison and his wife Mina, as well as Mr. and Mrs. J.N. “Ding” Darling. In 1933 during the Great Depression, Burgess addressed the Rotary Club with this uncanny statement: “We are praying for some new revelation of nature’s secrets which will create new industries, just as the radio, the automobile, the phonograph, the airplane were created. It may come through television, through a pocket device by which each individual can at all times be kept in touch with events the world around, or through the smashing of the atom, thus releasing the vast store of mythical energy which the atom is supposed to possess.”

In the 1940s, Burgess continued to discover new ways to use everyday materials such as a floating material for Navy lifejackets called typha, found in cattails, to replace kapok, the supply of which had been cut off during World War II. The material was also useful for absorbing oil slicks. On Burgess Isle he experimented with new methods of boat propulsion using vibrations. Burgess died in February 1945 before the war ended, leaving a legacy of invention and vision.

This article was taken from the Friends of the Randell Research Center Newsletter Vol 14, No. 2. June 2015.