Cayo Costa is a seven-mile long barrier island, with the Gulf of Mexico on the west and Pine Island Sound on the east. The north end at Boca Grande Pass is three miles west of the entrance to Jug Creek on Pine Island.

Captiva Pass at the south end is five miles due west of Pine Island Center. Although about 25 private homes exist on building lots platted in the early 1900s, most of the island is a state park encompassing more than 2,400 acres.

The island rests on a solid foundation of limestone from the Miocene (time period lasting from 24 to 5 million years ago), and the upper layer of this belongs to a Pleistocene (time period lasting from 2 million to 10,000 years ago) series of sediments called the Anastasia Formation, a mixture of coquina-based limestone, sand, and clay. According to geologist Richard A. Davis, Jr., of the University of South Florida, writing in The Geology of Florida edited by Anthony F. Randazzo and Douglas S. Jones, the nearshore subtidal Holocene ( time period lasting from 10,000 years ago to the present day) sediments beneath the present barrier islands are 4,200 to 4,500 years old.

Geologist Albert C. Hine and his colleagues published a study in the International Association of Sedimentology Special Publication, 2009, suggesting that the sparkling sand visible today on Florida west coast beaches eroded from the quartzrich Appalachian Mountains, carried downriver in fluvial channels during the Holocene. According to Davis, wave action and storms then lifted this sediment higher and higher onto Cayo Costa Island until beach foredune (a dune ridge, parallel to the shore, that is stabilized by vegetation) ridges became elevated enough to prevent overwash (the part of the wave that flows over the highest part of the dune or other structure and does not flow directly back to the ocean).

Barrier islands constantly move, and portions of them move faster than others. In 2005, researchers with the Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program noted that the National Geodetic Survey markers were difficult to find after Hurricane Charley because the bay shoreline appeared to have shifted east by four feet.

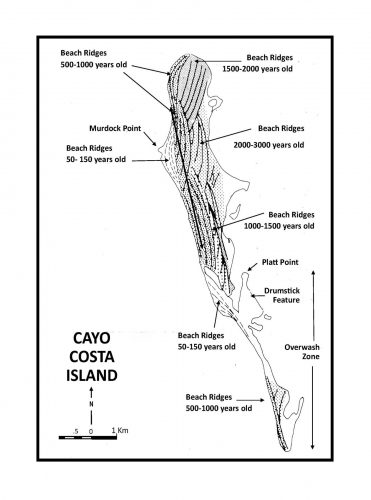

The island’s beach ridges and passes diff er in age as a result of dynamic processes. Sediment samples on dry land range in age from 3,000 years old to less than 100 years old, according to geologist Frank Stapor and his colleagues. As reported by Karen Walker in The Archaeology of Pineland and by William Marquardt in The Archaeology of Useppa Island, geological and zooarchaeological evidence suggests that the effects of sealevel fluctuations and storms may have eroded away the entire southern half of Cayo Costa at various times in its history. This thin, sandy area is still vulnerable to overwash and breaching; the most recent was in 2004 during Hurricane Charley.

Murdock Point on the west coast of Cayo Costa is described by Hine as a prograding (the process by which a beach or delta enlarges by progressive deposition of sediments) formation. A sand spit in the Gulf of Mexico emerged west of Cayo Costa in 1944. In very slow motion over fifty-five years, it “bumped into” the island, enclosing its own lagoon. A channel just wide enough for boats to enter from the Gulf remained open. Geologists predict the sand bar may continue to move eastward to enclose the lagoon completely, after which the water body may leach salt and become an inland freshwater lake.

On the eastern side of the island, sand formations shaped like drumsticks constantly rotate their sand spits according to tidal currents. Evidence of these formations may be observed on the map accompanying this article.

Cayo Costa offers a rare and valuable collection of ecological systems. The variables of moisture, salinity, and type of sediment, whether sand or muck, come together, attracting specifically adapted plants and animals and forming twelve classes of natural communities on the island. From beach dune to maritime hammock to coastal grasslands to marine tidal marsh and more, each unique system thrives today according to its own elevation and micro-environment.

Today the beaches provide nesting sites for endangered sea turtles and ground-nesting birds such as piping plovers. The eastern fringe of red mangroves calms the waters, making good habitat for fish nurseries and bird rookeries. Bald eagles and ospreys select the most prominent trees for nesting. The eastern waters provide a natural sanctuary for aquatic mammals such as manatees, dolphins, and river otters.

Five or more archaeological sites or pre-Columbian mounds exist on Cayo Costa. The sites on state land are protected by laws designed to preserve the integrity of the cultural deposits. The Mark Pardo shell midden, which dates from the Caloosahatchee IIA to IV periods (AD 500–1500), is composed of linear shell deposits that parallel the shoreline adjacent to a black mangrove forest. The site may have been first occupied when sea levels were lower. It covers an estimated thirty acres, and the mound ranges up to 5 feet above the ground. It is bounded by a private residence. This site was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1996 for its potential to yield information about past environments and Calusa use of barrier islands.

The privately owned Faulkner Mound is located on the south end of Cayo Costa. Facing east, it is a flat-topped mound of shells. At 15 feet high, the shell mound extends its fingers several hundred feet through mangroves on the bay side. The mound was named for an early 1900s family who built a house there. According to a local fisherman quoted by Robert Edic in his book, Fisherfolk of Charlotte Harbor, the family did not fish for a living but kept beehives and sold honey.

The Old Ware Mound is a shell mound with an associated borrow pit extensively vegetated by mature trees, cactus, century plant, yucca, and buttonwood. The mound is deteriorated, slumping, eroded, and weathered, and shows animal damage, roots, and human disturbance from the distant past. Two relatively undisturbed shell middens of unknown cultural affiliation and temporal period are also located on Cayo Costa. Finally, a collection of linear shell ridges lies under an area covering 650 feet north-south by 130 feet east-west. This prehistoric site of unknown age is preserved beneath two historic town sites from the 1800s.

The historic sites and trails are intriguing because of their connection to the historic families who still occupy the region today. These and other aspects of Cayo Costa’s early modern history will be discussed in the next article in this series.

This article was taken from the Friends of the Randell Research Center Newsletter Vol 12, No. 3. September 2013.