Way back in a 2005, Friends of the RRC Newsletter, Dr. John Worth (now at the University of West Florida) described a 1614 attack by Spanish forces on at least four Calusa towns, probably including the Pineland site (known at the time as Tampa).

His article served as an inspiration for archaeologists Charlie Cobb, Michelle LeFebvre, and Gifford Waters to successfully obtain a National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) grant to evaluate the location and condition of the Calusa sites involved in the hostilities.

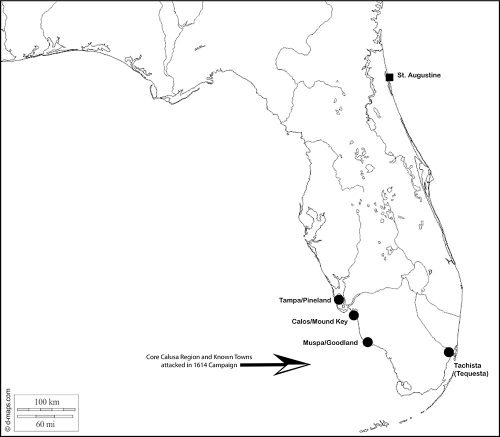

The attack on the towns of Tampa, Calos (Mound Key), Muspa (on Marco Island), and Tequesta (now sitting under tons of concrete in Miami) was in retaliation for a devastating raid that the Calusa carried out against the province of Mocoço in the present-day Tampa Bay area (Fig. 1). The colonial government in St. Augustine had been courting this province of Native American towns, a longtime rival of the Calusa, as a potential ally. The Calusa attack was an apparent attempt to punish their rival and undermine the partnership with Spanish Florida.

According to research conducted by Dr. Worth, two boatloads of Spanish soldiers set off from St. Augustine on their punitive expedition in 1614. Officials in St. Augustine probably felt this action was necessary to demonstrate to Indigenous allies that the Spanish Crown could be counted upon as a reliable partner.

The central goal of the ABPP initiative is to address the condition of sites known to have taken part in significant military actions in American history. It is not to conduct intensive archaeological investigations. In other words, projects are intended for preservation and planning purposes, rather than research. Our archaeological investigations have focused on systematic metal detecting survey at the two remaining preserved sites from the 1614 attack, Mound Key and Pineland. In addition, we have metal detected at the Mound House site on Estero Island, which straddled the fastest water route between Mound Key and Pineland.

used as a kind of anvil.

This work has revealed that there is one locality at Pineland that has yielded likely evidence of the attack or a Spanish encampment, including lead shot of a caliber used by Spanish muskets of the era and an iron bar that seemingly was used as a kind of anvil (Fig. 2). Similar shot has been found at Mound House. Our investigations at Mound Key have yielded a number of artifacts typical of an early Spanish colonial presence, including forged nails. It is difficult to relate these specifically to the 1614 attack, though, since a small garrison of Spanish soldiers and Jesuit missionaries lived at Mound Key in the late 1560s.

fashioned by the Calusa, a raw material

that must have been obtained from

Spanish sources

One of our more interesting artifact discoveries has been a small number of lead fishing plummets apparently fashioned by the Calusa, a raw material that must have been obtained from Spanish sources (Fig. 3). These artifact types have been discovered at Native American sites in southeast Florida as well. They serve as an important reminder that relations between Indigenous and European peoples were not always marked by violence. Groups like the Calusa were quick to take advantage of many of the material opportunities afforded by the arrival of European colonials.

This article was taken from the Friends of the Randell Research Center Newsletter Vol 21, No. 1 & 2. November 2022.