Discovering new knowledge from archaeological findings is always a thrill, for everyone from the new volunteer to the seasoned professional. As our Randell Research Center volunteers know, however, finding something is only the first step.

First, there is careful documentation at the site. We take notes, make sketches, and sometimes take photos. The findings are washed, allowed to dry, and then catalogued and re-bagged. We place catalog numbers on each artifact, and package special samples for storage until time for analysis. Fragile materials receive extra care, and may be packaged separately or stored under special environmental conditions.

In the laboratory, we examine the materials more closely and identify them based on previous studies that have been done on similar materials. Sometimes we weigh or measure objects, to help compare them with other such materials found elsewhere. In addition to pottery, stone, shell, and bone artifacts, archaeologists also study animal bones, shells, seeds, wood, and even samples of the soil itself for clues to what people ate and how their environment affected them. Sometimes the bones, shells, seeds, wood, and sediments can help us track environ- mental changes that occurred during the lives of past people. Finally, when all the studies are done, books and articles are published and public talks are given, so that everyone can benefit from the knowledge.

But what happens to all those artifacts and samples, not to mention the field notes and sketches, the photographs, and even the weights and measurements recorded in the lab? Quite simply, we keep it all. We refer to this accumulation of various materials as “collections” and collections are kept by museums such as the Florida Museum of Natural History, the parent organization of the RRC.

We keep all this stuff for a very simple reason – in the future we might want to look at it again. Or someone else might want to look at it. Our collections are similar to a library’s, except instead of book collections we keep archae- ological collections. Here again, the word “collections” may bring to mind artifacts, such as pottery sherds, shell tools, and other objects. But there is so much more. All kinds of samples (e.g., shells, bones, charcoal, sediments) and specimens (e.g., seeds, wood) are also parts of collections. Another large and very important component consists of a great variety of records associated with the excavations. Even when a collection like Pineland’s has been intensively studied for years, it still has great potential for future research and use in education and exhibits.

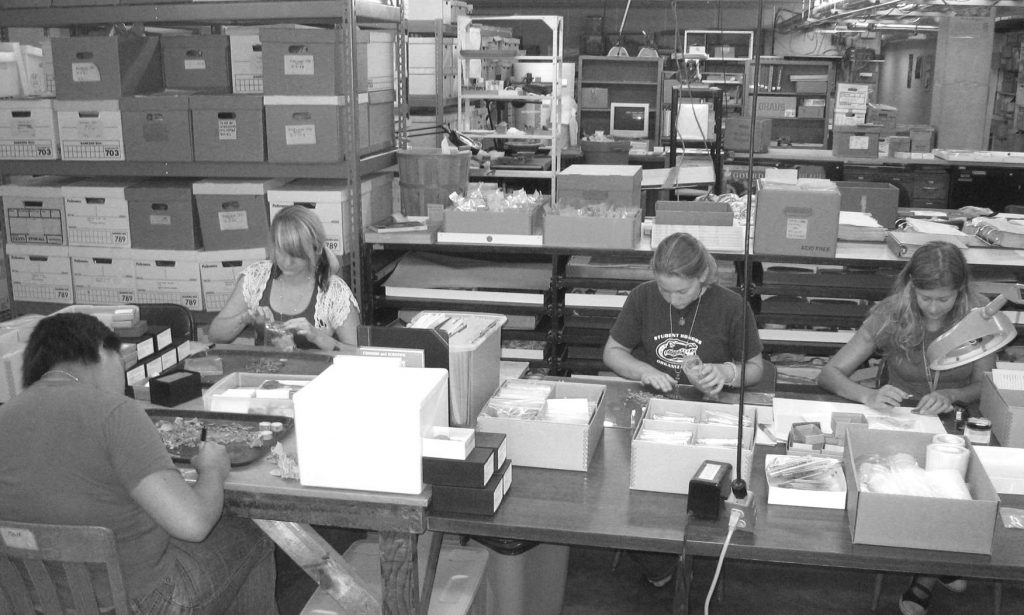

Sometimes we use the word “curation” to refer to the way we keep our archaeological collections. “Curation” comes from a Latin word meaning “to care for,” and that is what we do – we care for the collections by making sure they are safe from damage, and stored where they will not get lost or deteriorate. In October, we submitted a grant proposal for funding the final curation of the major archaeological collection that resulted from excavations at Pineland during the 1988-1995 time span. Our goal is to curate the collection following national standards so that it can be easily managed while at the same time be highly accessible for use. The curation project will take place in Gainesville, where the collection will always be housed.

Because the Pineland collection is so vast, we began a pilot project last fall (2005), curating a smaller collection, one produced in 1994 from Mound Key. All but the computerization of the collection is complete. As a result, this past summer, research began on this important and now accessible collection. Archaeologist Ann Cordell is analyzing the pottery. Zooarchaeologist Irv Quitmyer has prepared selected surf-clam shell specimens for microsampling, with the goal of detecting an environmental signal for the Little Ice Age. UF Anthropology senior Jack Stoetzel is sectioning and analyzing selected fish otoliths from the collection for his University Scholars Project. UF student interns recently assisted in sorting otoliths from the collection.

By now, you will have realized that archaeologists – especially those connected with museums, as we are – are involved with collections for a long time after that initial moment of discovery at the site. It’s a lot of work, but we think it’s worth it. If we do our job as curators properly, Pineland’s collections will be available to answer new questions for many years to come.

This article was taken from the Friends of the Randell Research Center Newsletter Vol , 5 No. 4. December 2006.