It is well known that the power and reach of the Calusa chiefdom constantly thwarted Spanish colonial ambitions to control all of Florida. Ponce de León, for example, died from a wound suffered in a battle while unsuccessfully attempting to plant a colony in Calusa territory in 1521. After founding St. Augustine in 1565, Pedro Menéndez established a small fort and Jesuit mission at the Calusa capital at Mound Key late in 1566. But deteriorating relations and violence led to the forced abandonment of the fort in 1569. Although European maps displayed the entire peninsula as part of La Florida, practically speaking the Spanish Crown had little success moving into the domain of Calusa leaders and their allies—effectively most of Florida south of modern-day Tampa.

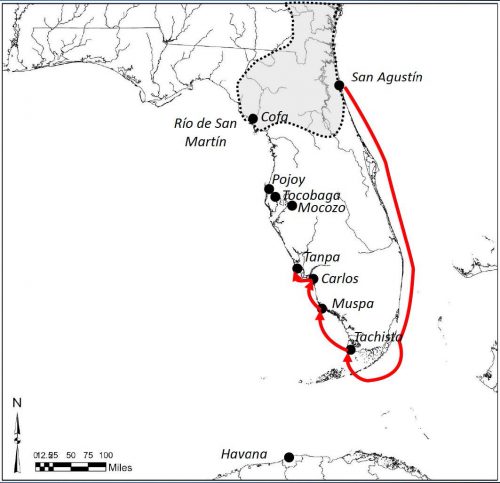

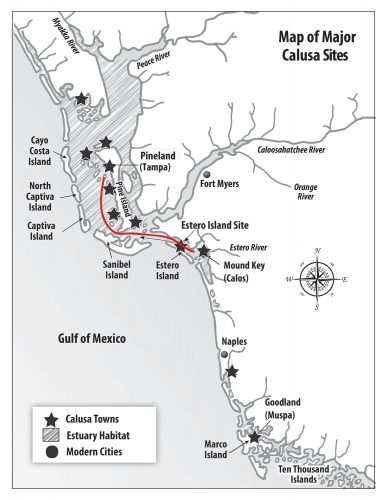

Colonial administrators at St. Augustine thus looked northward for Indigenous alliances. One was the Indigenous province of Mocoço, a powerful confederation in the Tampa Bay region. It turns out they were also long-time enemies of the Calusa. Concerned about the potential advantage Mocoço would gain with a Spanish partnership, in 1613 the Calusa sent a war fleet north and reputedly killed 500 people in two of their towns. Anxious to show Mocoço that they were dependable partners, St. Augustine sent out two small military boats in 1614 that attacked at least four of the major Calusa towns in retribution: Tampa/Tanpa (Pineland), Calos/Carlos (Mound Key), Muspa, and Tachista.

In 2022, University of Florida and Florida Museum of Natural History archaeologists Charlie Cobb, Michelle LeFebvre, and Gifford Waters received a grant from the National Park Service (NPS) to assess whether signs of these battles and their aftermath could be detected archaeologically. The NPS granting initiative, known as the American Battlefield Protection Program, supports research that identifies where significant battles may have occurred and provides educational information about their importance to American history. From a fieldwork perspective, the program requires somewhat of an “archaeology-lite” approach that emphasizes locating evidence of conflicts, while inflicting as little damage as possible to these important historic resources.

With that in mind, we decided to focus on metal detector surveys of Calusa sites to seek evidence of the Spanish attacks. We enlisted the assistance of archaeologists from the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology since they have a deep history of expertise in metal detecting battle sites. In addition, we worked with John Worth (University of West Florida), an archaeologist with expertise in Spanish colonial history and interest in the 1614 battles. Dr. Worth, who is adept at reading post-Medieval Spanish, managed to find and translate for us a remarkable document: a provision list for the expedition boats. Too long to reproduce here, some of the interesting supplies included a lot of food (heavy on the olive oil and pork), matchlock muskets (an early firearm technology that relied on a lighted fuse to ignite the gunpowder), tools such as axes and hoes, and a variety of goods (e.g., glass beads, knives) listed as trade items for Native Americans. Perhaps the latter were meant to gain support from disgruntled local groups who would help in their assault on the Calusa towns, although there is no evidence that ever occurred.

Project results

Muspa, located on Marco Island, has been heavily damaged by modern development, and Tachista on the south tip of the peninsula is not accessible. So, our investigations focused on Pineland and Mound Key. Our metal detector survey at Mound Key was successful at finding a number of objects that likely dated to the early colonial era. These ranged from wrought iron nails to scraps of brass left from working sheets of this metal. The difficulty with interpreting this material is that the Spanish presence there for three years in the 1560s may account for some of it. We did find one fired (deformed) lead musket ball in the 0.51 caliber range, typical of Spanish matchlock muskets. Some of the artifacts provided intriguing insights into Calusa crafting. For example, aside from the brass sheet fragments, we found several lead plummets, possibly made from remelting lead musket balls.

We did have more success at Pineland, where we found a cluster of early colonial-period metal objects just east of the Randall Mound. These included three musket balls, all in the matchlock musket size range (0.54-0.55 caliber), a wrought iron spike, a wrought iron nail, and part of an axe head. A particularly interesting recovery was a large iron bar. This is typical of the raw stock that Spaniards would carry on expeditions, useful for making into a variety of objects on the fly, so to speak. Our hypothesis is that these items may be indicative of a brief encampment by the Spaniards following the attack.

As we examined maps for the likely route of the boats, it occurred to us that they almost certainly would have passed the Mound House, or Estero Island, site. We gained permission to metal detect the eastern portion of the property, the side facing the sound where boats would have passed. Our efforts were rewarded with finding four lead musket balls, again in the size range typical of early Spanish muskets. This leads us to believe that the written Spanish record of the expedition only recorded the four largest Calusa towns that were assaulted, whereas one or more smaller undocumented settlements may have been attacked, as well.

The metal detector surveys did not yield evidence for large-scale conflict at any of the Calusa towns. It seems more likely that the Spanish soldiers engaged in short, punitive skirmishes. We surmise that the military expedition was largely a matter of demonstrating Spanish loyalty to the province of Mocoço, and of alerting the Calusa that St. Augustine had long-range military capabilities. Nevertheless, those capabilities were never sufficient for the colony of La Florida to extend its sovereignty over southern Florida.

Guest author Charles Cobb, Curator of History Archaeology, Florida Museum of Natural History