Destruction of Mound 4

On September 27, 2007, the sound of heavy equipment punctuated the late-afternoon ambience of Pineland, as a large backhoe removed about 5,000 cubic feet of the mound known as Brown’s Complex Mound 4.

The mound is on private property owned by Chris and Gayle Bundschu, who were building a house there. The Bundschus were following the requirements of the county health department, which had mandated a large excavation for the septic-tank drainfield, based on the size of the house.

Concerned that unmarked human burials might be disturbed, Lee County imposed a stop-work order pursuant to state statute. This was based on published archaeological evidence of Calusa Indians having buried their dead in elevated midden-mounds during the Caloosahatchee IIA period (A.D. 500-800). At the request of the property owners, Lee County planner Gloria Sajgo, and State Archaeologist Ryan Wheeler, Bill Marquardt proposed an investigation to determine whether or not human remains were present and to document the sedimentation layers for comparison with previous systematic work at the Pineland Site Complex.

This plan was acceptable to all, and the field investigations were undertaken by Bill Marquardt and Karen Walker on October 16-19 and October 22-26, 2007. We were assisted by two professional archaeologists working in the area who volunteered their time — Tom McIntosh and Eugene Chapman — and by archaeologist and RRC employee Michael Wylde. We are very grateful for their assistance.

We set in stakes at the corners of the drainfield excavation, and measured the elevation relative to the Pineland site’s topo- graphic map. Using hand tools, working from top to bottom, we cleared the vertical exposures (profiles) of the disturbed sediments, and pulled loose dirt away from the profile bases in order to reveal the maximum area for inspection. We took photographs of each of the exposed profiles to document the variously colored sediments.

When all the profiles had been cleaned and photographed, Karen created a measured, schematic drawing, noting general depositional trends and evidence of such features as activity surfaces, post molds, artifacts, and pits. We noted any artifacts or unusual materials in place in the profile diagram, then collected and systematically numbered them.

If human remains had been encountered during the profile documentation, these would have been marked and left in place and the provisions of state law followed. However, although many fish, mammal, reptile, and bird bones were observed and identified, we found no human bones. When the field drawings had been completed, we retrieved a series of representative sediment and shell samples, and submitted several samples for radiocarbon dating.

All artifacts discovered in the course of this investigation belonged to the owners, but they offered to donate diagnostic artifacts and items found in context to the Florida Museum of Natural History. The Museum agreed to curate them in perpetuity. The owners retained a representative sample of artifacts for display in the foyer of their new home.

Results

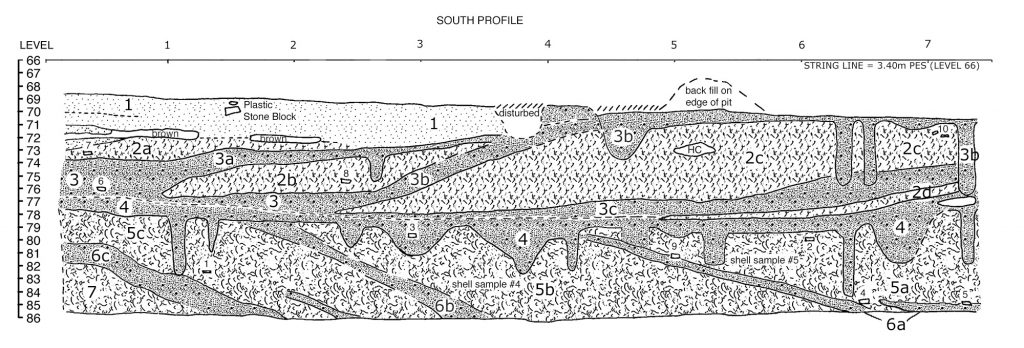

A quick look at the drawing and photos of the excavation shows several layers of variously colored sediments Generally, we think the darker-colored layers represent activity surfaces – that is, spaces where people lived, worked, and played. Some of these dark layers may be the floors of Calusa houses, while others may indicate common areas situated in front of people’s residences.

Extending down from some of these dark layers are long, narrow, dark streaks that probably represent the remains of long-rotted wooden posts. As the posts rotted, sediments from the dark layers filtered down into the voids left by the rotted posts; archaeologist call such features “post molds,” because they are literally molds of where posts once were.

Alternating with the dark layers are deposits of mollusk shells, animal bones, ashes, charcoal, broken pottery, and spent tools and other objects made of bones and shells. These lighter-colored layers probably represent episodes of refuse dumping, which archaeologists call “middens.”

Archaeologists refer to the various layers as “strata” (singular “stratum”), and they are numbered from top to bottom. Stratum 1 is a variable gray sandy deposit with fragments of shell, rock, modern debris, roots, and other disturbances. Stratum 2 is a dense shell deposit with light gray sand, animal bone, charred wood fragments, pottery sherds, and shell artifacts. Based on field observations, the most abundant shell is that of the lightning whelk, followed by pearwhelk, true tulip, fighting conch, oyster, and crown conch. Also present are banded tulip, horse conch, quahog clam, bay scallop, ribbed mussel, and surf clam.

The south profile reveals a series of four midden episodes separated by four sandy activity-surface strata (strata 3a, 3b, 3c). For this reason, we divided Stratum 2 into 2a, 2b, 2c, and 2d with 2a being the youngest (highest) deposit and 2d the oldest (deepest). The south profile clearly documents an eastward progression of both midden and activity surface deposits. Stratum 2a was radiocarbon- dated to about A.D. 1400 to 1460, the Caloosahatchee IV time period.

Strata 3 and 4, sometimes indistinguishable from each other, other times distinct, both contrasted in form, color, and content with the overlying shell of Stratum 2 and the underlying shell of Stratum 5. Both strata 3 and 4 document activity surfaces (associated with structures of some kind), are darker in color, and contain more sand and less shell than 2 and 5. Stratum 3 is a medium dark gray sandy sediment with much less shell, animal bone, charred wood, and artifacts. Its radiocarbon date is about A.D. 1210 to 1270, the Caloosahatchee III period.

Stratum 4 is a light gray sand very similar to Stratum 3. We think it represents an extensive activity surface associated with one or more structures of some kind. It may well have covered the entire space of Mound 4 and more. A radiocarbon date places Stratum 4 at A.D. 800- 980, indicating a Caloosahatchee IIB period occupation. Associated with both strata 3 and 4 are numerous postmolds. However, we can say nothing about the position, size, or shape of the multiple Calusa buildings that once stood here because the entire area between the profiles was removed by heavy machinery.

Strata 5, 6, and 7 are quite different from 2, 3, and 4. Strata 5, 6, and 7 represent an earlier sequence of habitation that sloped toward the west, toward Pine Island Sound. Stratum 5 is a very dense deposit of shells with sparse light gray sand, bone, charred wood, and artifacts. The shell assemblage is less diverse than that of Stratum 2 and there is much less animal bone. The most abundant shell types are lightning whelk, pear- whelk, and crown conch. A radiocarbon date indicates that Stratum 5 was deposited about A.D. 670 to 790, the Caloosahatchee IIA period.

Stratum 6 (with intermittent layers a, b, and c), is a light gray sandy deposit with much less shell, sparse animal bone, and few artifacts. No visible post molds are associated with Stratum 6, not surprising because in each case the strata slope to the west. The strata nonetheless appear to be activity surfaces. Stratum 7’s shell density and content are the same as that of the strata 5 series, except that 7 contains many more animal bones, primarily fish bones.

Stratum 8 (not visible on the south profile diagram) is different in appearance from all the others. It is a black sandy deposit with crushed shell and abundant bone, primarily fish bone. Shell types and their relative abundances are similar to strata 5 through 7 except that ribbed mussel is abundant and pen shell is present. We were unable to investigate any deposits that lie below Stratum 8. But if this area of Mound 4 is comparable to the area near Mound 2 where our 1988-1992 excavations were located, as we suspect it is, then the deposits beneath the septic drain- field extend downward at least another 1.7 meters (5 1/2 feet).

In sum, the information we were able to gather was limited due to the lack of context and the nature of the disturbance. We can say with confidence that the area destroyed by the drainfield excava- tion was intensively occupied by Calusa Indians, mostly in the Caloosahatchee IIA, IIB, III, and IV periods (A.D. 500-1500). No human bones or burial pits were found during the investigation of the septic drainfield pit.

Increased Protection for the Pineland Site

The property we call the Pineland Site Complex has been occupied almost continuously for 2,000 years. When the Spaniards arrived in the 1500s, Pineland was the second largest of all the Calusa towns. It has mounds almost three stories tall, a canal that went all the way across Pine Island (2 1/2 miles) to the other side, and some 20 centuries of archaeological deposits from which we can learn, not only about the native Indian people but also about environmental changes through time. For all these reasons, the site is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, and has been so listed since 1982. Many people are under the impression that this means that the site is protected, but this is not true.

When our neighbors dug out a drainfield for their septic tank, destroying a large part of Mound 4, they did not break the law. In fact, they did exactly what the County Health Department had told them to do. Had we been able to consult about this plan before the destruction began, perhaps some alternatives could have been suggested. The Bundschus were cooperative, allowing us to document the layers in the destroyed part of the mound. We appreciate this, but it would have been better if we could have had a conversation about it beforehand.

The destruction of Mound 4 came to the attention of the Lee County Historic Preservation Board, which proposed to designate the Pineland site as a county historical resource. This means that if a major earth-moving project or construc- tion project is planned, whether on public or private property, there will be an opportunity to discuss the best way to go about it and try to protect and preserve the Pineland archaeological site as much as possible. Public hearings were held in late 2007, and in January, 2008, the Pineland site was officially designated as a county historical resource. This means that in the future, when major excavations are contemplated, such as for a swimming pool or septic tank, there will be time to plan for the best way to protect and preserve the Pineland Site Complex.

This article was taken from the Friends of the Randell Research Center Newsletter Vol 7, No. 3. September 2008.