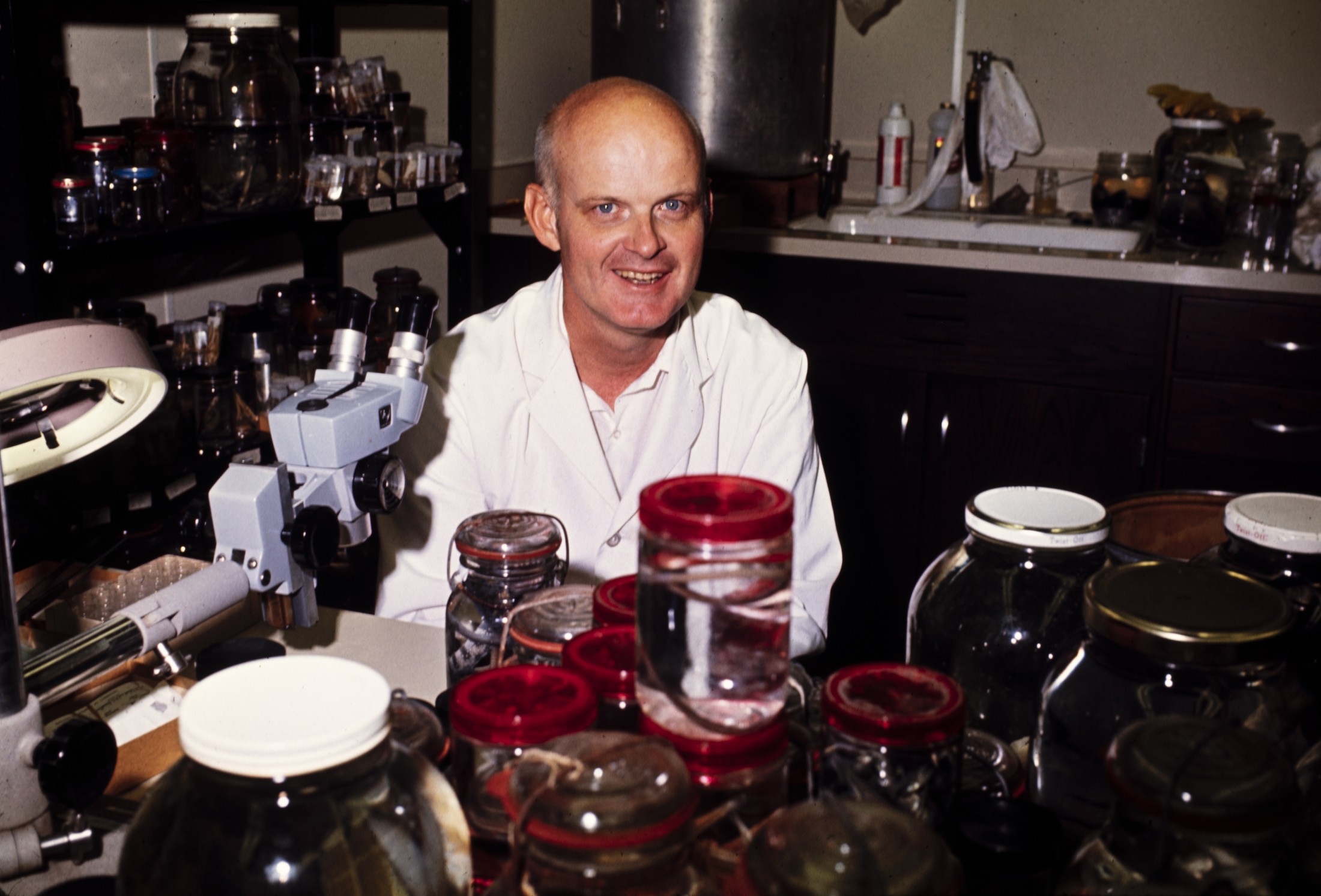

Carter Rowell Gilbert, former curator emeritus of ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History, passed away peacefully earlier this year on Jan. 6 at the age of 91. A memorial service was held on Saturday, June 11, attended by friends, family and colleagues to commemorate his life and achievements.

Gilbert was a sharp researcher known for his prodigious memory and encyclopedic knowledge of whatever he turned his mind to. He had the distinction of building a storied and successful career while garnering a reputation for being kind, affable and helpful to everyone he worked with.

“Carter had an exceptional knowledge of the diversity of freshwater and marine fishes, and that, coupled with his congenial and accessible nature, made him one of the leading ichthyologists in the U.S.,” said Larry Page, the current curator of ichthyology at the Florida Museum.

Gilbert was born on May 23, 1930 in West Virginia, but he spent his early formative academic years in the Midwest, attending universities in both Ohio and Michigan. It was there, not far from the banks of the Great Lakes, that he fell in love with freshwater fishes, indulging in ichthyology courses as an undergraduate and pursuing them as a major line of inquiry in graduate school.

His first taste of research came in 1951, when he began studying the ecology and natural history of the stonecat, Noturus flavus, a small catfish that lives in Lake Erie and nearby streams. He next turned his attention to the systematics of another freshwater group, the highscale shiners in the genus Luxilus. Despite having conducted his analysis on the relationships of these fishes before the widescale advent of DNA sequencing, his treatment has been largely validated by later work.

Before finishing his Ph.D. at the University of Michigan, Gilbert was offered a temporary position at the Smithsonian Institution, where early on he demonstrated an agile academic versatility by switching his focus to hammerhead sharks. He might have continued indefinitely at the Smithsonian had he not been approached again with another tantalizing job offer, this time from the Florida Museum. There was an opening for an ichthyology curator there, and the chair of the department of natural history wondered if Gilbert might like to apply.

Despite the vast size and scale of the national holdings at the Smithsonian, Gilbert felt a particular pull to the state museum, located in Gainesville. Nestled between the southern reaches of southeastern United States’ waterways — with all their astounding diversity of freshwater fishes — and the equally alluring diversity of tropical Atlantic Fishes, the small college town held the promise of satiating Gilbert’s passions.

The Florida Museum also had the benefit of being embedded in an academic institution, which would allow Carter to impart his knowledge to succeeding generations of scientists by mentoring graduate students. He went on to advise several Ph.D. and master’s students while serving on dozens of student committees during his long tenure at the museum.

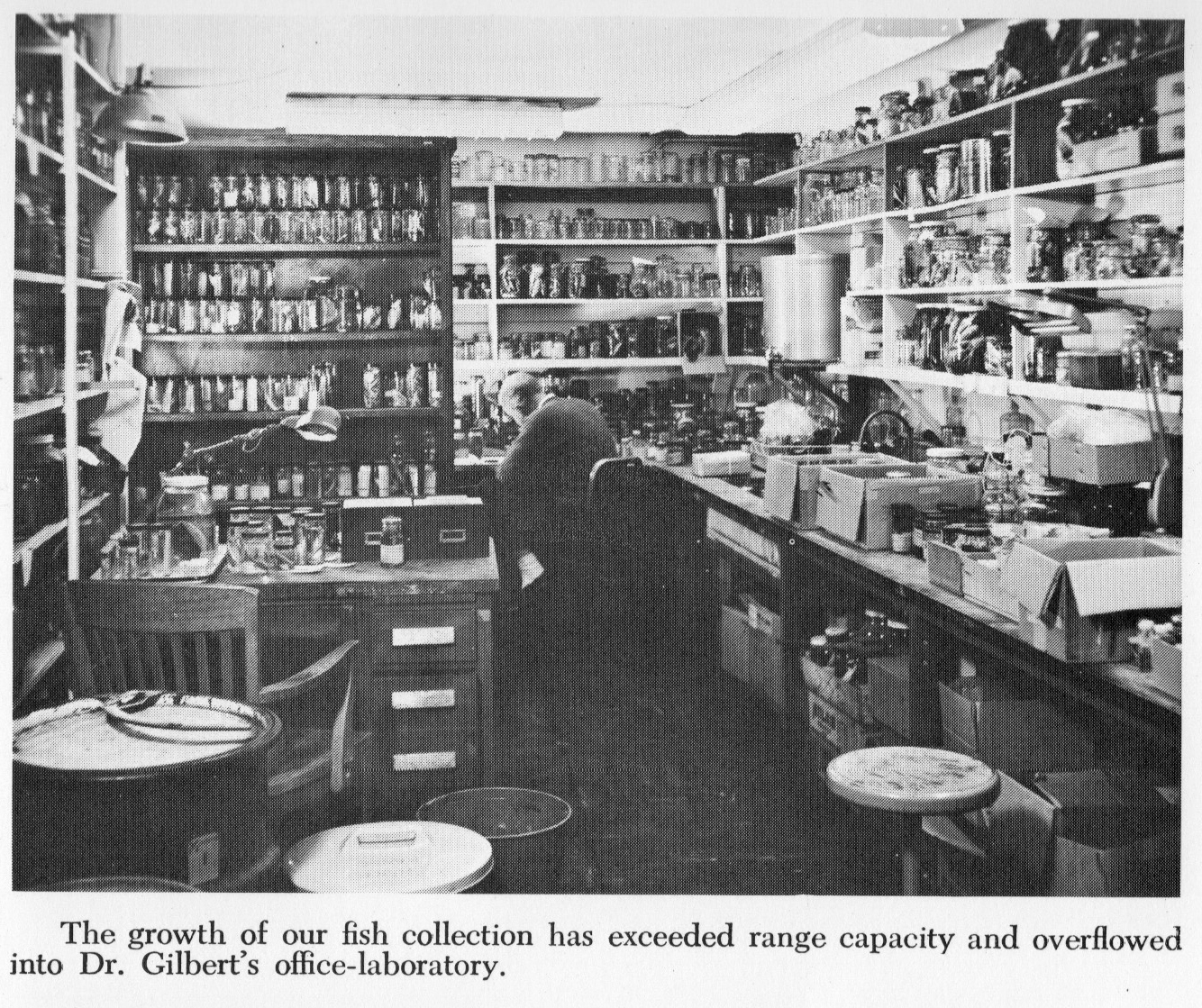

The contrast between the brimming collections at the Smithsonian and the more modest assemblage housed at the Florida Museum was immediately apparent.

“When I arrived, I was shocked at how small the collection room was after having experienced the facilities at the UMMZ and USNM. The number of catalogued lots was less than 10,000, mostly local freshwater fishes,” Gilbert was quoted as having said in a short biography published in the journal Copeia.

From that humble beginning, Gilbert spent the next 37 years of his career helping transform ichthyology at the museum into the one of the largest fish collections in the U.S., second only to the Smithsonian.

“He brought the collection to national prominence by growing it through his own collecting efforts and by accessioning several important regional collections,” said Stephen Walsh, one of Gilbert’s former Ph.D. students.

In addition to his curatorial work and research, Gilbert spent a significant amount of time cataloging what was quickly becoming an extensive collection.

“He did a vast amount of identification work, which was incredibly important, more than he’s credited for, because his work predated the digitized era,” said Robert Robins, ichthyology collection manager at the Florida Museum.

Gilbert officially retired in 1998 but remained active as curator emeritus long afterward. Of his many significant contributions to the field, Gilbert co-authored the “Atlas of North American Freshwater Fishes,” a definitive handbook for fish experts, naturalists and enthusiasts in the region. Throughout his academic career and beyond, colleagues have honored his memory and legacy by naming six new species after him, including the Gulf Coast Pygmy Sunfish, Elassoma gilberti, a native of Florida’s streams and rivers.

Florida Museum photo by Zachary Randall

“Carter will be greatly missed by his colleagues who will always remember him as an intelligent and kind individual with a very pleasant demeanor and positive attitude,” Walsh said.

You can find more information on Carter Gilbert’s life and legacy in the 2004 biographical sketch in Copeia, published by the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, and in a remembrance by Stephen Walsh in the spring issue of American Currents, published by the North American Native Fishes Association.

Many of Gilbert’s friends have asked about making a gift in his memory, and the Museum suggests gifts be directed to the Dr. Carter R. Gilbert Endowment, which supports undergraduate and graduate student education, curation and research in ichthyology at the Florida Museum of Natural History.