The southwest coast of Florida boasts one of the longest and most enduring histories of coastal lifeways in North America. It is also a hurricane hotspot between the months of June and November each year. The 2025 hurricane season started on June 1, and as we now sit in our homes anticipating spiraled clouds on satellite maps and trails of spaghetti models speculatively drawing the lines of storm paths across the Atlantic and Gulf, I cannot help but think about the Calusa that once called this region home and lived through hurricane seasons.

For nearly two thousand years, up until the mid-18th century, the Calusa were the Indigenous peoples that inhabited the shorelines and islands of southwest Florida. Recognized today as ancestral to Florida’s federally recognized Tribes, the Calusa lived within estuarine and marine environments and negotiated within their social structures to flourish among the ever-changing wetland ecosystems of the region. The archaeological record shows us that they had extraordinary resilience in the face of climate change and environmental challenges, including hurricanes. Their success was in large part a result of their deep environmental knowledge, innovative land and seascape infrastructure, and cultivation of social capital within and between communities.

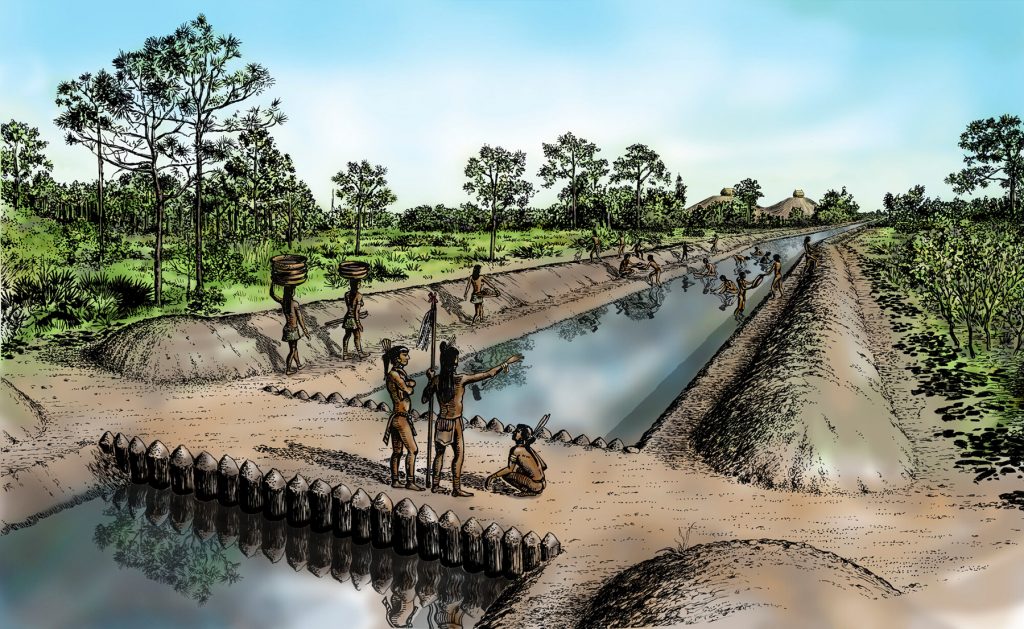

For the Calusa, knowledge of the environment was crucial to hazard resilience. Intimate, generational understandings of inland, coastal, estuarine, and freshwater ecosystems and biota allowed the Calusa to anticipate and prepare for environmental changes – both predictable and unanticipated. For example, they constructed canals, smaller tributaries, and watercourts which enabled them to control and manage the flow of water during daily, weekly, or monthly (e.g., seasonal) shifts in hydrology. These included predictable hightides and heavy summer rains but also punctuated events like hurricanes and storm surges. Built water systems also supported the ability to capture fish en masse to feed large populations and ensured reliable canoe travel for the transport of people and goods before and after disruption events.

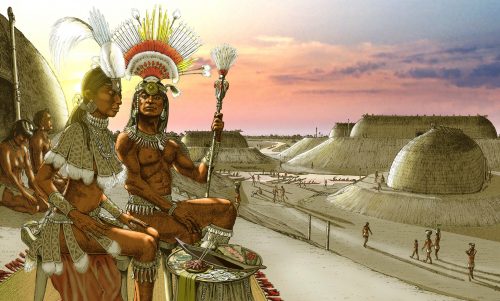

In addition to deep environmental knowledge, ‘social capital’ was also important to Calusa society and their ability to respond to times of change and challenge. Social capital can be described as the value of relationships and social networks to provide cohesion and support within and between groups of people. Based on historical sources, the Calusa were a highly stratified society with centralized rule under a Calusa king or cacique (pronounced kuh seek). Spanning numerous communities along the southwest coast, the cacique was the leader of a politically complex social structure that emphasized collective action and labor within and between communities.

Social capital would have been essential to achieving large land- and seascape development projects, including not only the construction of canals and water courts, but also the large mounds and artificial islands many Calusa communities lived on. The construction and maintenance of such infrastructure not only required the organization of people, but also the sharing of knowledge and skills across the community and strong social bonds.

Mounded landscapes helped the Calusa to live among environmental hazards such as seasonal flooding or wetland inundation, as well as episodic storm surge events.

Today, the results of Calusa ingenuity and lifeways are perhaps best recognized by the remnants of their shell mound architecture and canals preserved across public and private conservation lands in southwest Florida, including the Pineland site at the Florida Museum’s Randell Research Center on Pine Island. At sites such as these, I am reminded that the Calusa were a remarkable example of a society that thrived and sustained itself in what can be considered both a bountiful, and at times hazardous, coastal environment. Their ability to understand their local environments, anticipate larger weather events, as well as build, sustain, and mobilize collective efforts undoubtedly allowed them to manage the risks posed by living in southwest Florida

Nearly five months into the 2025 hurricane season, I find thinking about the Calusa is helpful to remembering that we are part of a very long coastal history. Although our current society is much vaster across space and different from social and political perspectives, we can still learn a great deal from the Calusa approach to coastal living. As we see our community bonds tested and solidified around hurricane events, especially in recent years, we are also empowered to work together to foster social and cultural capital across communities to build a resilient, supportive structure that can help our society grow and continue to flourish before and after storms. Recognition of the interdependence between people and the environment will help our resources, economy, and society adapt and last in southwest Florida.

Guest author David Outerbridge UF/IFAS Extension Lee County, douterbridge@ufl.edu