Maria Vallejo-Pareja, a graduate student at the University of Florida, recently received the Estes Memorial Grant from the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. This is the second year in a row that a UF student has earned the Estes grant, with Lazaro Viñola Lopez being the most recent recipient in 2021 for his work on Caribbean lizards.

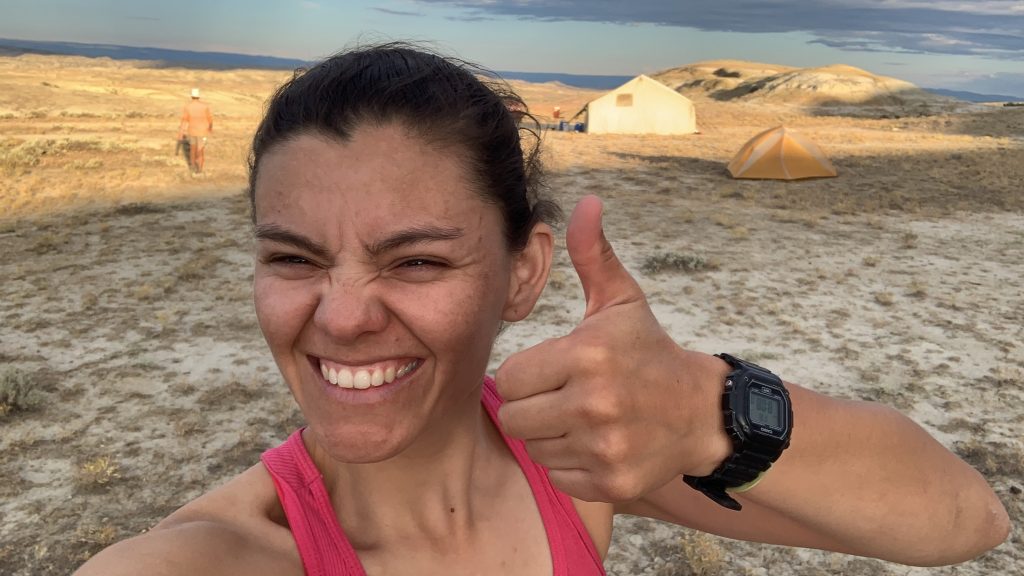

Photo courtesy of Maria Vallejo-Pareja

Vallejo-Pareja received the grant for her research on fossil frogs as part of her dissertation, and she plans to use the funding to pay for upcoming field work in Panama. The Estes grant is one among several offered by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology and was established to fund non-mammalian research, including fish, dinosaurs, birds and snakes. Vallejo is the first person to receive this grant to study frogs.

She joined the department of biology in 2018 and is co-advised by David Blackburn, the curator of herpetology at the Florida Museum of Natural History and associate chair of the Department of Natural History, and Jonathan Bloch, the curator for vertebrate paleontology and chair of the Department of Natural History.

Vallejo-Pareja works with frog fossils from North and Central America, which she uses as a proxy to study the environments of the past by investigating biological traits such as body size. Frogs’ sensitivity to environmental conditions makes their fossils an important resource for scientists attempting to determine how ecosystems have changed through time.

“Frogs have a very unique physiology,” she explained. “Modern frogs have a lot of contact with their environment through their skin, which is very permeable. Pretty much everything that goes into the environment can go into their bodies really quickly.”

Vallejo-Pareja’s interests lie mostly with tropical frogs, and she plans to supplement her work in Panama with visits to museum collections in South America. She’s also performed field work with Bloch in Wyoming, where she and other paleontologists sifted through massive bags of sand looking for bones. Frog fossils are so small that she often had to examine her findings under a microscope to make sure the bones weren’t rocks in disguise.

“It takes a lot of time back in the lab sorting through thousands of screens. About 90% of the time, it’s not even a fossil,” she said.

She intends to continue this kind of work in Panama, where she’ll be the first person to study the country’s fossil frog record.

Source: Maria Vallejo-Pareja, maria.vallejo@ufl.edu

Writer: Brian Smith, brian.smith1@flmnh.ufl.edu