It may seem as though the same brown moths circle your porch light each night. But a two-year survey of moths from a single backyard highlights the exceptional diversity of these insects and how they ebb and flow with the seasons.

The study, based on nearly 25,000 moths, shows how their numbers and species fluctuate month to month in North Central Florida, with peak moth abundance in May coinciding with spring plant growth. Certain species persist even when temperatures are freezing and insects seem few and far between.

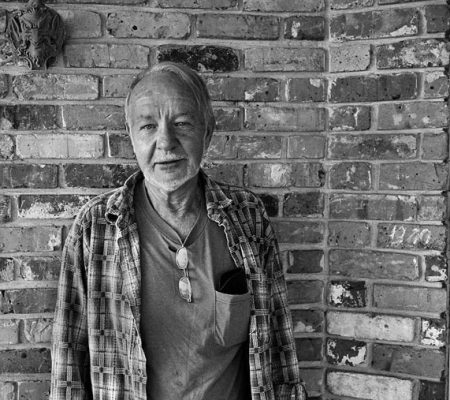

Renowned lepidopterist George Austin collected the moths from his backyard on the edge of Paynes Prairie from 2005 to 2006. Austin, then the collections manager of the Florida Museum of Natural History’s McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity, gathered 44 moth families and more than 800 species.

Photo courtesy of Phil deVries

Ten years after his death in 2009, Austin’s collecting efforts continue to provide important insights into the area’s moths and their seasonality.

“There’s a big change in general from year to year, not only in what species are present, but when,” said Andrei Sourakov, the study’s lead author and collections coordinator of the McGuire Center. “When observing George’s effort, I saw it could be changed from just another biodiversity study into something bigger. By sampling a bit more systematically we could try to understand the underlying patterns of seasonality and changes from year to year.”

Moths play key roles as plant pollinators and food sources for predators that range from tiny spiders and bats to grizzly bears. As caterpillars, they feed on plants and drive plant evolution by influencing the development of chemical defenses.

Still, little is known about how they interact with their ecosystems.

Austin collected moths in his backyard from about 8 p.m. to 2 a.m. twice every week, using a common “mothing” technique: a white sheet illuminated by a black light. He would often head to the McGuire Center in the middle of the night to begin preserving newly captured specimens.

While his dedication to collecting might seem extreme, Sourakov, who worked closely with Austin, said “it was just part of his mindset.”

“I don’t think there was another person like George out there who created such large collections by himself,” Sourakov said. “He was a real machine as far as collecting goes.”

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

Sourakov cataloged and analyzed the specimens Austin collected in 2006 with those from 2005, looking at moths by family and genus and patterns within genera.

Different moth species dominated at varying times of the year, with five families accounting for more than half of the total sample. In every genus, there were clear “winners” – one or two species that made up the majority. These close relatives peaked at different times, likely to avoid competing with one another for resources, Sourakov said. Dominant species, as well as the overall community composition, differed significantly between the two years.

Florida has a combination of temperate and tropical plants that contributes to a highly diverse moth population, Sourakov said. Austin’s sample encompassed moths from both forest and aquatic environments.

“Moths can provide a framework for understanding local ecosystems as a whole,” he said.

Sourakov and Austin’s study showed that the largest population peak is in May, coinciding with the end of the dry season when spring rains bring fresh plant growth and act as an environmental cue for moths to emerge and lay their eggs. But green plants don’t always equal high moth diversity, Sourakov said.

“Here in Florida, we have so many evergreen trees. Why don’t we have peak diversity year-round if there are so many plants? Well, it’s an illusion,” he said. “These leaves are actually not very edible to young caterpillars. At the end of the dry season, most of the leaves are not more nutritious than cardboard.”

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

The study also showed that moth populations consistently dipped to their lowest points in December. But Sourakov said a collector who overlooked the sluggish winter months would miss unique species that fly in cooler temperatures.

“When it’s cold and sometimes freezing, you would think, ‘Oh, well, there’s certainly not anything flying around that I couldn’t catch in May or August,’ but that’s not the case. Both years, we had more than 30 species in December that were not there in May,” Sourakov said. “Species adapt to harsh environments to reduce predation and competition, taking advantage of resources that maybe aren’t available during the summer.”

Collecting efforts like Austin’s are likely to yield new species discoveries, which, in the case of moths, often take specialists to identify, Sourakov said.

“Usually, discovering a new species doesn’t involve a ‘Eureka!’ moment at the collecting sheet,” he said. “Taxonomists travel between museums and look at specimens of interest for their scientific project and if they see something that looks new, they borrow it, describe it in a scientific paper and then it returns to the museum as a ‘type specimen.’”

Sourakov said Austin conducted many other surveys throughout the world. He published more than 100 scientific papers on butterflies and moths with various collaborators and described many new species.

“George left an almost unsurpassed legacy,” Sourakov said. “As a collector, he’s probably one of the greatest.”

The study was published in News of the Lepidopterists’ Society.

Source: Andrei Sourakov, asourakov@flmnh.ufl.edu, 325-273-2013