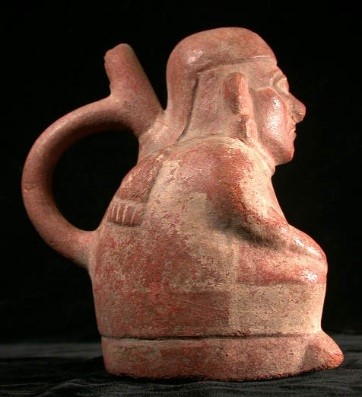

Plate 1.

P2291

Peru, North Coast

Moche, Early Intermediate Period (A.D. 100-600)

Stirrup Spout Bottle

Bichrome Pottery

Dimensions: H 16 cm x W 12 cm x D 15 cm

(AC)

This Moche stirrup spout bottle depicts a seated figure, identified as a female by the headdress and other details of costuming.[1] She is wearing a long garment with painted step-fret motifs. Her sitting pose is very apparent in the side view, where we see her bent knees, her back hunching forward and her hands resting on her knees. Moche pottery is characterized by admirable craftsmanship and exceptional realism in both painting and sculptural modeling.[2] Though her almond-shaped eyes seem to bulge out, there is great interest in naturalism shown in the facial features and signs of aging, such as the nasolabial folds around her mouth. Women in Moche art are rarely represented and when they are they often depicted in sexual poses.[3] This figure is characterized as a high status individual by her large circular ear spools,[4] as well as the step fret motif on the dress, symbols of power, prestige and authority.[5] A bag-like object over her shoulder resembles a coca bag. A similar bag is seen in a ceramic vessel depicting a monkey with coca paraphernalia.[6] The use of coca is still very common in the Andes, and it is consumed by men and women to help build stamina, relieve fatigue and other effects caused by high altitude.[7]

Similar Examples:

- Benson 1972:fig. 6-21.

- Clifford 1983:fig. 24.

[1] Clifford 1983:145.

[2] Villacorta 2007:66.

[3] Benson 1972:142.

[4] Stone 2012:103; Stone 2002:194.

[5] Benson 1972:152.

[6] Donnan 1976:117.

[7] Kauffman-Doig 1998:108.

Plate 2.

P2288

Peru, North Coast Lambayeque-Chimu,

Late Intermediate Period (A.D. 750-1375) Bridge-Spouted Vessel Blackware Pottery

Dimensions: H 23.3 cm x W 18 cm

(AC)

This blackware vessel features a pedestal base and a bridge spout, common characteristics in Lambayeque ceramics.[1] One spout is tall and tapering and the other is a blind spout depicting a seated human figure. Most Lambayeque ceramics were made using press molds and the pottery was smudge-fired, creating a dark black color.[2] The blind spout has a figure that contains a whistle, apparently a trait that originated on the south coast. The long, tapering spout can be linked to Wari influence. [3] The cross-legged figure is adorned with circular earspools, a beaded necklace and a fan-like headdress. Such headdresses are similar to the tumi headdress worn by an icon called the Lambayeque Lord or Sican Lord, a culture hero characterized by a crescent headdress.[4]

Similar Examples:

- Sawyer, 1966:fig. 82.

- Stone 2012:figs. 142, 144.

[1] Donnan 1992:90.

[2] Donnan 1992:92.

[3] Sawyer 1966:60.

[4] Stone 2012:168-169.

Plate 3.

2008-6-6

Peru, North Coast Chimu,

Late Intermediate Period (900-1470 A.D)

Curassow Stirrup Spout Vessel Blackware Pottery

Dimensions: H 22.1 cm, W 14 cm, D 11.8 cm

(AC)

Birds are abundant in the art of the ancient Andes, for they played a very important role in folklore.[1] The twin curassows on this stirrup spout vessel are depicted in a naturalistic manner, with great attention to detail seen in the modeling of the heads and crests. Most likely they represent males, as they are depicted with well pronounced bill knobs, a feature characteristic of male curassows. Although not very common, representations of twin birds are also found in Moche art.[2]

Birds like the curassow were highly valued for colorful plumage that was used in complex featherwork. The most highly valued feathers were those with vibrant colors and luminous character like those from macaws, ducks, flamingos and curassows.[3] Featherwork might have been one of the most prestigious mediums in the ancient Andes.[4] Like Moche ceramics, Chimu vessels often feature naturalistic depictions of birds, but Chimu vessels can be distinguished by their burnished charcoal surface and the appliqued element at the base of the spout, sometimes representing a small animal.

Similar Examples:

- Anton 1972:fig. 83.

- Tello 1938:152.

[1] King 2012:10.

[2] Proulx 2006:139, fig. 5.175; Tello 1938:152.

[3] King 2012:12.

[4] Stone 2012:182.

Plate 4.

2008-6-5

Peru, North Coast

Chimu, Late Intermediate Period (1000-1476 A.D.)

Double-chambered Bridge-spout Vessel

Blackware Pottery

Dimensions: H 21 cm, D 24.6 cm, W 14.5 cm

(AC)

This double-chambered Chimu vessel features chevron-like designs on both ends and a pattern of raised dots called stippling. The Chimu created “pressed” background designs on many of their vessels. They are known for their black-ware ceramics, characterized by a dark charcoal color and polished sheen. They often used molds to mass produce highly sculptural ceramic vessels.[1]

The vessel itself depicts a woman embodying a valuable Spondyllus shell, a form represented by the jagged patterns on the vessel.[2] Her pointed headdress resembles the hinge of a shell. Female traits are highlighted by the long strands of hair falling over her shoulders. Her hands clasp the sides of the vessel, and her head forms the blind-spout on one chamber. The bridge to the other spout may have been used as a handle, which joins the woman’s head where here is a hole. This hole is capable of making a whistling sound when the liquid levels change from one chamber to the other by rocking the vessel.[3]

Similar Examples:

- Clifford 1983:Pl. 83.

- Lumbreras 1974:fig. 191.

- Stone 2012:fig. 159.

- Stone 2002:fig 554.

- Museum of Fine Arts Boston number:495.

- Penn Museum number:31823.

[1] Stone 2012:184.

[2] Stone 2002:244.

[3] Stone 2012:186.

Plate 5.

101429

Peru, North Coast

Chimu, Late Intermediate Period (A.D. 1000-1470)

Stirrup Spout Bottle with Ray Effigy

Blackware Pottery

Dimensions: H 23 x D 19 cm

(EB)

The body of vessel is an effigy of a ray, an animal commonly represented on pottery and textiles.[1] The representation may be a manta ray, a fascinating animal that seems to be flying when it leaps out of the sea.[2] A stylized monkey located at the juncture of the spout is a common feature on Chimu stirrup spout vessels, but is also found earlier on Moche ceramics.[3]

Similar Examples:

- Tello 1938:131.

[1] Benson 1997:117.

[2] Benson 1997:118-119.

[3] Sawyer 1966:59-60.

Plate 6.

102231

Peru, North/Central Coast

Coastal Wari, Middle Horizon (A.D. 700-900)

Face-Neck Jar

Redware Pottery

Dimensions: H 36.2 cm x D 28 cm

(EB)

The collector attributed this jar to the Piura Valley on the North Coast of Peru, but it closely resembles an example excavated by Max Uhle at Chimu Capac in the Supe Valley. Although the Supe Valley marks the northern limits of the Central Coast, in the Middle Horizon the site of Chimu Capac used North Coast techniques with pottery designs executed by press-molding rather than painting.[1] The vase personifies an aspect of nature linked with deified snakes.[2] A human head forms the jar’s neck, and raised serpentine elements twine around the shoulders, here symbolizing mountain peaks. The figure’s hair ends in snake heads, representing “hair like snakes,” an ancient Andean metaphor found in Chavin art.[3]

Similar Examples:

- Menzel 1977:fig. 68.

- Proulx 1968:Pls. 15a, b.

- Olsen 1978:85.

[1] Menzel 1977:32, fig. 68, Middle Horizon 3.

[2] Benson 1997:108-109.

[3] Rowe 1962:16, figs. 27, 29, 34.

Plate 7.

96029

Peru, Central Coast

Chancay, Late Intermediate Period (A.D. 1000-1470)

Weaving Basket and Tools

Plant fibers, wood, cotton, bone and clay

Basket Dimensions: H 6 cm, L 28.5 cm, W 14 cm

(AC)

The dry climate of the Andes helps conserve many delicate items and materials that often degrade in the tropics. The Andean region is characterized by environmental extremes, with the second-highest mountain range flanked by the world’s driest coastal desert and the Amazonian rainforest.[1] The desert coast has helped preserve the most fragile materials, like cotton, camelid fiber, feathers and wood.[2] Burying the dead and their treasures in the dry sands of the desert helped preserve them.[3]

This weaving basket is a good example of such preservation, as it contained an array of different objects, such as yarn balls, spindles for spinning, weaving battens, as well as some textile fragments, not pictured here. The weaving basket was once attributed to Paracas, but is more closely comparable to other examples from the Chancay culture, dating 1000-1470.[4] The basket itself is made out of twined plant fibers, most probably reed. There are 10 weaving spindles of varying size and thickness, some still wrapped with yarn. Constructed of bone and clay, these spindle whorls are decorated with depictions of birds and geometric designs such as nested diamond motifs.

Similar Examples:

- Musee de l’ Homme 1988:fig. 433.

- Lowe Art Museum 1990:fig. 148.

[1] Stone 2012:9.

[2] Stone 2012:11.

[3] Boytner in Young-Sanchez and Simpson 2006:45.

[4] Craven 1971; Lowe Art Museum 1990:133.

Plate 8.

96033

Peru, Central Coast

Chancay, Late Intermediate Period (A.D. 1000-1476)

Mummy Mask

Wood and Clam Shell

Dimensions: larger piece: H 31.8 cm, W 11.4 cm, D 8.6 cm; smaller piece: H 21.8 cm, W 1.6 cm, D 3.8 cm

(AC)

This wooden mask shows a stylized human face displaying clam shells for eyes with pupils that were once painted or glued on the surface.[1] Traces of red paint survive along with facial features such as eyebrows, a smiling mouth and a prominent nose. Masks like this one have been found in burials as representations of a mummy bundle face.[2] Very frequently these masks have holes punched in at the top of the forehead where a headdress or hair was attached that provided the mummy with a naturalistic head of hair.[3] The widespread use of funerary masks indicates the importance of ancestor cults among the Chancay.[4] Their living descendants honored the deceased, usually by adorning them with intricate woven textiles, headdresses and masks.[5] These masks were valuable for their role in representing the deceased rather than for the materials used in their construction.[6] The amount of work involved in preparing the bodies of their ancestors provides evidence of a strong belief in the afterlife among the Chancay.[7]

Similar Examples:

- Lavalle 1982:33.

- Waisbard 1966:Pl. V.

- Kauffman-Doig 1998:120.

[1] Kauffman-Doig 1998:120.

[2] Quilter 2005:141.

[3] Waisbard 1966:53.

[4] Quilter 2005:141.

[5] Stone 2002:264-265, 247.

[6] Quilter 2005:138.

[7] Kauffman-Doig 1998:122.

Plate 9.

101423

Peru, Central Coast

Chancay, Late Intermediate Period (A.D. 1000-1476)

Whistling Vessel with Human Effigy

Bichrome Pottery

Dimensions: H 25 cm x D 15.5 cm

(EB)

Chancay pottery, one of the dominant styles on the Central Coast, is relatively crude in workmanship.[1] The characteristic colors are bichrome, with violet-gray painted on white, as on this whistling vessel. As early as 900 B.C., whistling vessels developed as single chambered bottles on the South Coast of Peru.[2] Later on, whistling vessels incorporated two drum-like chambers, connected in the middle by a conduit, like our example. A tall spout adorns one of the chambers and a strap handle connects with a human effigy on the other chamber. A whistle outlet is cut into the effigy chamber and when the spout is blown, or when the liquid is tipped from one chamber into the other a shrill sound is emitted.[3]

Similar Examples:

- Donnan 1992:101, fig. 195.

- Lumbreras 1974:fig. 196.

[1] Lumbreras 1974:191.

[2] Sawyer 1966:75, fig. 97.

[3] Stat 1979:3.

Plate 10.

102225

Peru, Central Coast

Chancay, Late Intermediate Period (A.D. 1000 – 1476)

Female Figure

Bichrome Pottery

Dimensions: H 46.9 cm x W 27.3 cm, D 11.2 cm

(AC)

Characteristic of the Chancay culture, this female effigy known as a cuchimilco, can be distinguished from male effigies by the female genitalia and breasts.[1] These characteristics emphasize human fertility, and such effigies found in graves are interpreted as funerary companions.[2] Depicted with arms raised, this female adopts a pose associated with praying or adoration.[3] Her wing-like arms appear to be connected to her shoulders, mirroring the triangular shape of her head, which is crowned by a painted headdress. The holes on top of the head are for attaching now lost metallic ornaments.[4] This figure has pierced ears, suggesting that it would have worn ear ornaments, symbols associated with high social rank.[5] Painted designs on the jawline resemble tattoos. Spectacle-like rays painted on the face are fairly common on female effigies.[6]

Similar Examples:

- Cuesta Domingo 1980:216-217.

- Lavalle 1982:34, 73.

[1] Kauffman-Doig 1998:122.

[2] Sawyer 1975:84.

[3] Stone 2012:187.

[4] Cuesta Domingo 1980: 189; Stone 2002:247.

[5] Stone 2002:194.

[6] Stone 2012:187.

Plate 11.

10228

Peru, Central Coast

Chancay, Late Intermediate Period (A.D. 1000-1476)

Effigy Jar

Bichrome Pottery

Dimensions: H 36 cm x 21.5 cm

(EB)

This jar represents a male wearing ear spools and holding a ritual drinking cup that may symbolize an offering of maize beer (chicha), a fairly common theme in Chancay effigy vessels. Chancay ceramics reflect a decline in craftsmanship resulting from the mass production of pottery.[1] They are considered to be relatively low in artistic caliber because they were mold-made and decorated with poor quality slips that were applied carelessly.[2] Three-dimensional details such as the cup and flanged headdress were added with stamps.

Similar Examples:

- Donnan 1992:99, fig. 188.

- Lumbreras 1974:192, fig. 195.

- Clifford 1983:Pl. 171.

[1] Sawyer 1966:66.

[2] Donnan:1992:98-99.

Plate 12.

102240

Peru, South Coast

Nasca, Early Intermediate Period (A.D. 100-600)

Panpipe

Bichrome Pottery

Dimensions: H 15.24 cm x W 10.2 cm

(AC)

This ceramic pipe has red painted designs on a white-slip background. Ancient pipes like this one differ from modern versions as they have a series of sealed tubes, instead of open cylinders.[1] Red zig-zag lines decorate the end of the tubes and a straight line frames the mouthpiece with seven tubular cylinders, which would produce different notes for each cylinder played.[2] Music was a well-developed tradition in the Andes, so it comes as no surprise that the Nasca created flutes, pipes, rattles and trumpet-shaped horns.[3] Music was essential in the ancient Andes for rituals and perhaps also for shamanic communication with the spirit world.[4]

Similar Examples:

- Stone 2012:61.

- Stone 2002:587-589.

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Accession Number 1984.332.

- Brooklyn Museum, Accession Number 41.433.

[1] Stone 2002:276.

[2] Stone 2002:276.

[3] Lumbreras 1974:132.

[4] Stone 2012:80.

Plate 13.

94744

Peru, South Coast

Nasca, Early Intermediate Period (A.D. 100-600)

Bottle with Bridge Spout

Polychrome Pottery

Dimensions: H 12.7 cm x D 10.5 cm

(EB)

Nasca polychrome ceramics are extraordinary in both technical and artistic execution, displaying a prolific range of symbols and religious motifs.[1] Painted in red, orange, gray, white, and brown, this bottle depicts a mythical creature known as the “Horrible Bird,” a theme that first developed in the middle period of Nasca art.[2] Shown here consuming human limbs, this rapacious creature most likely represents a stylized condor, a carrion-eater.[3]

Similar Examples:

- Proulx 1968:fig. 9b.

- Wolfe 1981:49, fig. 62.

- University of Pennsylvania Museum number SA-2911.

[1] Donnan 1992:42-43, 52.

[2] Proulx 1968:86-87; Wolfe 1981:8-14.

[3] Benson 1997:89.

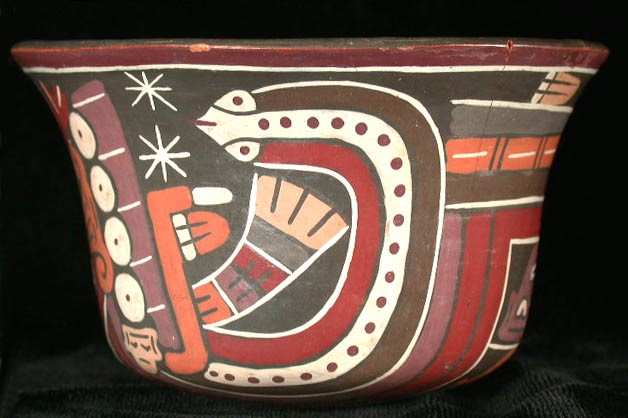

Plate 14.

102239

Peru, South Coast

Nasca, Early Intermediate Period (A.D. 100-600)

Bowl with Anthropomorphic Mythical Being Bowl

Polychrome Pottery

Dimensions: H 6.4 cm x W 10.46 cm

(AC)

The Nasca are widely known for their brightly colored ceramics, made with an array of colored slips and designs that become increasingly more complex over time.[1] This polychrome bowl relates to the Middle Nasca style, characterized by intricate abstract imagery and a great variety in colors.[2] Two snake-like creatures appear with star motifs alongside a supernatural creature known as the Anthropomorphic Mythical Being, a figure combining human traits with animal masks and animal features. One of the most repeated portrayals in Nasca ceramics, the Anthropomorphic Mythical Being probably has its origins in textile imagery from Paracas.[3] A feline or fox mask with long whiskers represents a golden mask worn over the mouth of this supernatural being. Three trophy heads, one in its right hand, two hanging from the headdress, are complemented by a set of five on the bottom and back of the bowl. Such trophy heads have been associated with agricultural fertility, as well as the decapitation of war enemies.[4]

Similar Examples:

- Anton 1972:68-69.

- Donnan 1992:86.

- Proulx 2006:figs 5.1, 5.11, 5.12.

[1] Donnan 1992:50.

[2] Stone 2012:80.

[3] Proulx 2006:62.

[4] Proulx 2006:56.

Plate 15.

94751

Peru, South Coast

Nasca, Early Intermediate Period (A.D. 100-600)

Kero

Polychrome Pottery

Dimensions: H 11.43 cm x W 10.66 cm

(AC)

Nasca ceramics are known for their masterful use of polychrome paint. Black outlining of all the forms shows the skill of Nasca artists. This kero has two drilled holes close on the rim, signs of an ancient repair made with twine laced through the holes. It belongs to the Late Nasca Style, characterized by taller and narrower forms, less variety of color, and abstract rayed deities.[1] In this late style, the deity represented is fantastical with a long protruding tongue and tentacle-like forms projecting from the head and body.[2] This drinking cup depicts three registers, and painted black and white quadrants on the bottom. The top and the lower registers depict motifs like step frets and double-headed snakes, represented here in a form closely resembling Andean textiles. In the middle register, the hands and legs of the beings are clearly depicted but their bodies have been replaced by abstract emanations called signifiers.[3] The middle register on this vessel shows two rayed deities known as the Proliferous Anthropomorphic Mythical Being, a more complex version of the mythical being from the Middle Nasca Style.[4]

Similar Examples:

- Proulx 2006:figs. 5.16, 5.17, 5.18.

- Blasco Bosque and Ramos Gomez 1986:figs. 33, 76, 78.

[1] Donnan 1992:52.

[2] Proulx 2006:71.

[3] Proulx 1968:17.

[4] Proulx 2006:69-70.

Plate 16.

94752

Peru, South Coast

Nazca, Early Intermediate Period (A.D. 400-600)

Parrot Effigy Jar

Dimensions: H 11.4 cm x W 16.5 cm

(EB)

The face of the parrot seems on this jar is relatively naturalistic and lugs on either side of the body represent the bird’s feet. This is a relatively rare example of a modeled animal image from the Late Nasca period, a time when modeled human figures were preferred.[1] The flared shape of the opening on this vessel is in keeping with that period, as are the designs depicting trophy heads spilling blood on a complex version of the Anthropomorphic Mythical Being.[2] The high standards of Nasca polychrome pottery continued through most of the later phases of Nasca culture, but number of colors employed are somewhat reduced when compared with Middle Nasca pottery, which used up to ten or twelve colors.[3]

Similar Examples:

- Blasco Bosqued and Ramos Gómez 1986:50, no. 25.

[1] Sawyer 1966:127.

[2] Blasco Bosqued and Ramos Gómez 1986:50; Lumbreras 1974:130, fig. 138.

[3] Sawyer 1966:126.

Plate 17.

A8961

Peru, South-Central Coast and Highlands

Wari, Middle Horizon (A.D. 400-1000)

Tunic Fragment

Wool Tapestry Textile

Dimensions: 32 cm x 24.6 cm

(AC)

Andean textiles are among the finest works of art ever produced by human civilization.[1] Prominent characteristics of Wari textiles include an emphasis on rectilinear designs that are repeatedly rotated.[2] This textile fragment was part of a Wari tunic, characterized by repetitive iconography, colors, and composition in a tightly woven tapestry. The rows and columns of figural imagery are commonly known as the face-fret motif.[3] The central theme has been identified as winged warriors or staff deities with profile faces.[4] The step fret and scroll motif may symbolize the wings of such characters depicted in profile on the Sun Gate at Tiwanaku. [5] The faces are symbolized by an open eye represented by a circle with a tear track running down its eye, and the mouth is a C shape outlined in black.

Andean textiles were critical to the life and culture of its people, serving as a medium to display status, the spread of ideological concepts, and as tribute offered to the ancestors and gods.[6]

Similar Examples:

- Bergh 2012:159, fig. 144.

- Lavalle 1984:93.

- Lehmann 1975:71, fig. III.

[1] Boytner in Young-Sanchez and Simpson 2006:45.

[2] Stone 2012:153.

[3] Bergh 2012:159.

[4] Lavalle 1984:93.

[5] Stone 2012:155, fig. 118.

[6] Boytner in Young-Sanchez and Simpson 2006:45.

Plate 18.

101422

Peru, South Coast

Wari, Middle Horizon (A.D. 600-900)

Drinking Cup with Bird Motif

Polychrome pottery

Dimensions: 16.2 cm x 14.4 cm

(EB)

The stylized bird on this cup represents a falcon or hawk, both birds of great symbolic importance to the cultures on the cultures of Peru.[1] This drinking cup is known as a kero, a form typical of the Wari culture in Peru and its counterpart at Tiwanku in Bolivia during the Middle Horizon. Keros were used for drinking chicha, a mild intoxicant consumed during rituals. Most keros of this period are painted with polychrome designs and some are also adorned with modeled effigy heads.[2] This one may be from the Supe River valley, for it has close counterparts with examples excavated at the end of the 19th century by Max Uhle at the site of Chimu Capac.[3]

Similar Examples:

- Lumbreras 1974:fig. 184a.

- Menzel 1977:fig. 46b.

[1] Benson 1997:81, fig. 60.

[2] Lumbreras 1974:fig. 164.

[3] Menzel 1977:29-33, fig. 46b.

Plate 19.

101431

Peru

Chimu-Inka, Late Horizon Period (A.D. 1476-1534)

Aryballos Bottle

Polychrome Pottery

Dimensions: H 22.9 cm x W 19.1 cm

(AC)

This bottle is done in a provincial style known as Chimu-Inka, created by skilled Chimu artisans who copied Inka style ceramics.[1] The form is known as an Aryballos, because it resembles ancient Greek vessels.[2] A rounded base, globular shape and tall slender neck with a flaring rim make the Aryballos one of the most distinctive Inka forms.[3] Such vessels would be used to hold chicha, a fermented corn beer consumed in ceremonial rituals.[4] These bottles were placed in shallow holes made on the ground, where they could easily be tilted for pouring into drinking vessels.[5] The small scale of our example suggests that the vessel was used for individual servings of chicha, like the small vessels found in burial caves at Machu Picchu.[6] Despite its diminutive size, this bottle has strap handles where a tumpline could be attached for transportation, as illustrated in an early account by Huaman Poma.[7] The lug below the neck is designed to hold the tumpline in place, but here it is very shallow, serving only a decorative purpose.[8] The bottle displays an array of different painted designs, including diagonal lines and a checkerboard pattern — a very common Inka motif used in tapestry weavings.

Similar Examples:

- Donnan 1992:219.

- Menzel 1977:fig. 17B.

[1] Donnan 1992: 112; Stone, 2002 252.

[2] Cabello 1988:27.

[3] Donnan 1992:108.

[4] Cabello 1988:27.

[5] Cabello 1988:27.

[6] Burger and Salazar 2004:127.

[7] Cabello 1988:25.

[8] Burger and Salazar, 2004:127.