Elephant-like tusks. A toe bone of an ancient condor. Even a snapping turtle with a smaller turtle coming out of its nose.

Some of the discoveries being made at the Florida Museum of Natural History’s new dig site in Williston, Florida, are odd and seemingly out of place, to say the least. Animals you’d expect to see in Africa, Asia or South America, like rhinoceros and llamas, are common finds. But that’s what makes the site so exciting, says vertebrate paleontologist Jon Bloch.

“This is not the kind of thing you can experience every day in just any place,” said Bloch, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Florida Museum on the University of Florida campus.

To reach the new dig site where a plethora of ancient creatures are being pulled from North Florida’s prehistoric rock layers, UF photographer Hannah Pietrick and I traveled to a patch of dry earth in a clearing of forest outside of Williston, Florida. About 40 miles from the modern day coastline, it’s hard to believe the site was once an ancient river that flowed into the prehistoric Gulf of Mexico.

Over millions of years, sea levels fell and the coastline receded. The river dried up, leaving its bones covered in layers of sand.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

At least, until a few were uncovered by a local Williston landowner, who then contacted paleontologists at the Florida Museum of Natural History. That’s when Bloch got involved.

For the past year, museum researchers have been digging against the clock. They need to remove as many fossils as they can, as quickly as possible. Dig sites are expensive to operate, prolonged exposure to sunlight and cycles of wetting and drying disintegrate the fossils, and eventually the property owner will need the land back for other uses.

“Concentrations of fossils like this are rare, especially from this age, and it is likely that a lot of finds go unreported when they are found. You have to have all the planets align to make this work,” Bloch said.

Volunteers are an essential part of making this happen. The museum scientists have opened the site to UF students and anyone else over 15 years old willing to get dirty and serve as a field volunteer through May 21 (sign up here).

The more sand and clay that’s moved, the more rare things will be found, Bloch said, standing on the edge of the crater-like dig site and pointing to some of the locations where the most fascinating fossils have been unearthed.

“If you want to set yourself up for exciting discoveries, you look in a place where nobody’s ever looked before. And that’s what we’ve got here,” Bloch said.

“It’s a time and a place where nobody’s ever looked before. So that’s great for us but it’s also an opportunity to offer the community something we haven’t been able to offer in over a decade, and that’s the chance to come out here and make really new discoveries along with us,” he said.

In the lab

In the preparatory lab at the Florida Museum, the shelves are overflowing with plaster jackets holding mystery fossils from the Williston site waiting to be pieced back together and studied.

The lab is where thousands of 5.5 million-year-old fossils ranging from turtles and alligators to ancient versions of elephants and rhinoceros pulled from the dig site are brought to live their second life.

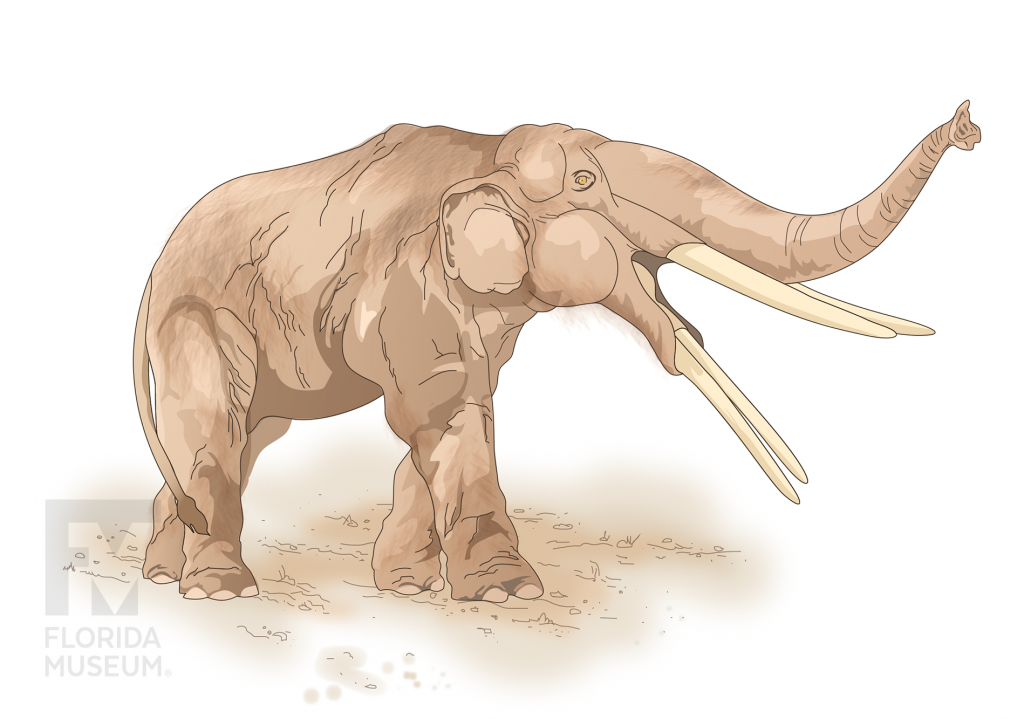

Jason Bourque, a fossil preparator in the Museum’s vertebrate paleontology division, sat at a table where he slowly removed dirt and rock from a large femur bone that once belonged to a gomphothere, an elephant-like creature that once roamed North Florida. Gomphotheres are one of the most common fossil animals found at the Williston site, Bourque said.

A section of the site, in fact, is almost entirely gomphothere bones — an elephant graveyard of sorts.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

In collections cabinets in the room next door, the fragile bones of the oldest swans ever found east of Arizona sit in tiny paper boxes. Other fossils of ancient fish, frogs, otters, rhinoceros, salamanders, shrews, snakes, quail — many the oldest ever found in Florida — and possibly the oldest specimen of the American alligator, sat quietly behind the metal doors.

Illustration by Michael McAleer

The Williston site is comparable to the famous Gray Fossil Site in Tennessee, which also dates to the late Miocene (7 to 4.5 million years ago) and has yielded rare discoveries like two nearly complete ancient rhinoceros skeletons, a new plant-eating badger and only the second occurrence of a red panda in North America.

Like déjà vu, several of the Gray discoveries are being repeated at the Williston site, including the same species of rhinoceros. But there’s still one animal that remains elusive — the red panda, which isn’t a panda at all, but a mammal more closely related to raccoons and skunks. It resides today only in the eastern Himalayas and southwestern China, but 5.5 million years ago its distribution may have included North America, at least as far south as Tennessee.

The Williston site is the first opportunity museum researchers have had to search for the red panda and other rarely found late Miocene fossil animals in North Florida.

In the field

One of the reasons paleontologists love river sites is because they give you all sorts of different snapshots of animals: those that lived in the water, those that drank from it and animals that were washed in from elsewhere, like the sea or surrounding forests.

But when it comes to rivers, you can’t dig in just one spot.

“We could be on the top of a very extensive formation. We just don’t know yet how big the river was,” Bloch said. “But because it’s a river, it is variable where things are and what they are. We’re getting layers representing bends in the river where there’s bones all over.”

Volunteer Peter Roode piped in from the small square where he tediously removed dirt with a tiny shovel, “Did you tell them about the Lincoln penny I found last week?” he asked, then laughed. “Just testing their credulity.”

Both the Gray and Williston sites represent a rare slice of time prior to the Great American Biotic Interchange (GABI), an event that occurred about 3 million years ago after the land bridge in what is now Panama joined South and North America, and both freshwater and land animals began to migrate between the two continents.

Around 5.5 million years ago when gomphotheres, saber-toothed cats and rhinoceros were drinking from the Williston river, a lot was happening, Bloch said. Sloths and a few other South American natives were already beginning to appear in North America. Other animals, like the gomphotheres, would soon head south.

Illustration by Michael McAleer

“It’s a look at the world just prior to the mass invasion of South American animals, and the dispersal of many species from North America,” Bloch said. “Up here it’s particularly interesting because we have post-GABI sites in North Florida but we haven’t had a clear picture of the pre-GABI, especially from an estuarine environment.“

Then, out of nowhere, volunteer Mary Ellzey shouted, “Found something!”

The something turned out to be a toe bone of a baby gomphothere.

“It’s not every day you find a gomphothere bone, I’ll tell you that,” Bloch said, dusting off the fossil. “I’m sure the first day I ever went fossil hunting, I did not find a gomphothere toe.

“It’s not a giant snake, but it’s pretty cool,” said Bloch, who discovered Titanoboa, the largest fossil snake ever found.

While paleontologists have plenty of fossils of animals found at sites across North America, like various species of gomphothere, the distribution of some other animals, including the red panda, is unclear.

Bloch said finding a red panda would help paleontologists paint a picture of what Florida looked like just prior to the GABI. If they eventually find that there are no red pandas in Florida, it will show a real contrast between the types of animals found in the Appalachians and those in North Florida during the Miocene.

The more snapshots of environments Bloch and colleagues can gather, the better they will understand the ancient North American terrain.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

“The degree to which we have snapshots across the landscape at different slices of time can help us develop a more realistic perspective of what the terrestrial ecosystems were like back then, and also help us understand what happened during the greatest experiment in invasive species that’s ever been run – GABI,” he said.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

The presence of something like a red panda, something so characteristic of Asia, at the Gray site is not something anyone expected. And, yet, there it was, and it may be in Florida as well, Bloch said.

“It’s always so interesting to go in your own backyard and see things that are so different from what’s here today,” Bloch said. “Finding a red panda at Gray is one of the many examples of how reality documented in the fossil record can be stranger than the imagination.”

Back at the Florida Museum, Richard Hulbert, the vertebrate paleontology collections manager, showed off some of the smaller —in size— discoveries from the site. A shrew bone the size of a grain of rice, pieces of swan and a toe bone of what is likely a saber-toothed cat.

“We know a saber-tooth is there…we just have to find it,” he said prophetically. A few weeks later in mid-December 2016, volunteer Bill Buhi found a severely crushed but fairly complete skull of a saber-toothed cat.

As for the red panda…

“Any given day we could find something new to science,” Bloch said.

Originally published by UF News in January 2017.