Volunteer Harry Lee has been transferring shells to the Florida Museum one car load at a time for eight years.

Nearly every Wednesday at 7:05 a.m. for the past eight years, Dr. Harry G. Lee drives 90 minutes from his home in Jacksonville to volunteer in the Florida Museum of Natural History Invertebrate Paleontology Division, usually accompanied by a trunk full of shells.

Lee began donating his shell collection to the museum on the University of Florida campus in 2010, and continues to personally transport increments of the nearly 1 million shells, estimated to be the largest private collection in the world.

“The ability of museums to absorb a collection is limited by the manpower and other resources of a department,” Lee said. “Especially with a collection of this magnitude.”

Today, Lee, a self-proclaimed museum rat and citizen scientist, considers his collection to be an educational resource for future researchers.

Florida Museum Malacology Collection Manager John Slapcinsky wholeheartedly agrees.

“Harry’s website posts species lists of mollusks for many sites in Florida, and because his identifications and data are so well-trusted, these lists are a valuable resource,” Slapcinsky said. “UF students in our lab and in the invertebrate paleontology lab often use them to guide identifications of their own research specimens.”

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

Lee began collecting shells at the age of 6, while visiting his grandmother in South Orange, New Jersey. Her next-door neighbor, Max Hammerschlag, a retired scissors-maker, collected shells and taught Lee how to properly document and catalog different species. Hammerschlag gave the young Lee shells to take home and examine, and he started his collection in 1947.

Although his dedication was minimized by the distractions of athletics and girls in high school, he knew he would continue to collect shells.

“It was the one great continuum in my life,” Lee said.

As an attending physician in internal medicine, Lee’s true passion never faltered. Every night he would return from a tiring day at the hospital and office, strip off his lab coat and get to work on his shells.

During weekends and vacations, he traveled to distant lands hoping to discover hidden, rare shells, and would regularly scale cliffs, dive in deep oceans and trudge through swamps on his days off.

His travels took him to Australia, Fiji, Hawaii, Kenya, Mexico, the Philippines, Somalia, Tahiti, Tanzania, and numerous West Indian islands, to name just a few.

“Wherever the mollusks are, I will go,” Lee said.

The most important discovery of his career, however, occurred while crawling in his own backyard in Jacksonville in 1980. Lee found a new-to-science species of carrot glass snail, Dryachloa dauca. It is the only species in its genus, and Lee and the late Florida Museum curator Fred Thompson described and named it that same year.

Lee’s collection, estimated to be worth about $1 million, is stored mostly in his basement, where every inch of wall space is covered with bookshelves and cabinets that hold the precious specimens. These include his sentimental favorites: the 36 shells Lee named and the 18 shells named after him.

His most highly prized shell is the left-handed variant of the sacred shell of Hinduism, the Indian chank. This species is rare, with only 1 in 600,000 shells coiling in the opposite direction.

Lee said he loves uncovering a shell’s story and believes that “shells are intrinsically beautiful.”

“They form templates of evolution in beautiful, mosaic patterns,” he said.

This belief and his collection also resulted in the creation of his book, “Marine Shells of Northeast Florida.” In a joint effort with about 50 shell club members over more than two decades, the Jacksonville Shell Club published the book in 2009.

With the profits from book sales, Lee and the other members created a $2,000- $2,500 academic grant in 2010 for master’s and doctorate students, awarded annually by the Conchologists of America Inc., an international society for shell enthusiasts.

After seven years, only about one-third of the collection has been transported to the museum, and Lee does not know when he will finish.

“It’s a work in progress,” he says.

Florida Museum image by Kristen Grace

Volunteer of the Year

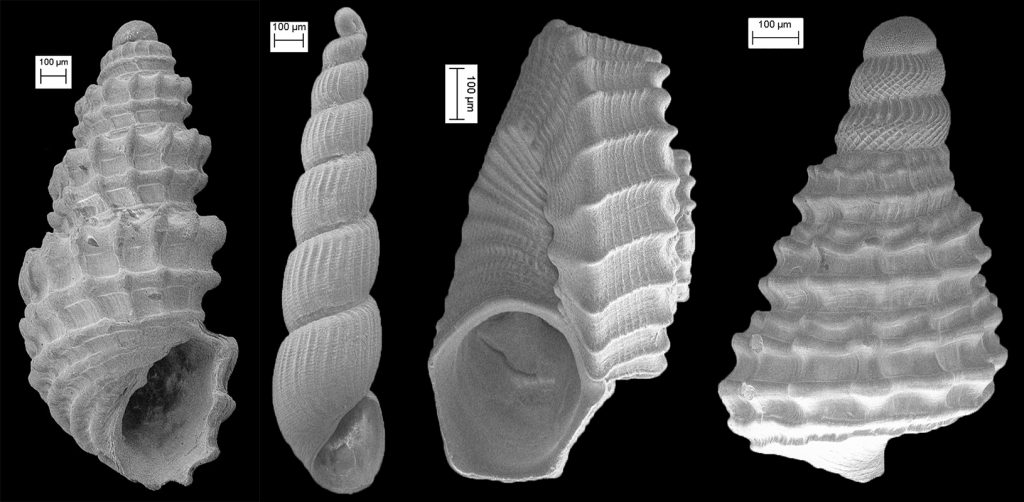

Lee has volunteered more than 2,000 hours integrating his shells into the museum’s collections and also working with fossil micromollusks, defined as shells less than 5.5 mm in diameter. He removes and identifies these specimens from sediments he and others collect and photographs them with a scanning electron microscope.

In 2017, he was honored as the museum’s James Pope Cheney Volunteer of the Year for research and collections, nominated by museum malacologist Slapcinsky and Roger Portell, the museum’s invertebrate paleontology collection director.

Slapcinsky said Lee is well-known nationally and internationally among the malacology community as one of the most giving and knowledgeable amateurs.

“Almost every molluscan collection by a mollusk enthusiast that has been donated to the (Florida Museum) Malacology Division in the last 40 years bears Harry’s fingerprints in the form of his identification labels,” Slapcinsky said. “He has corresponded with numerous amateurs and professionals, not only helping with identifications, but tracking down rare publications, sharing specimens and facilitating interactions between the lay community and the professional community.”

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

Portell said Lee is responsible for building the museum fossil micromollusk collection into an invaluable resource.

“Micromollusks are not common in museum collections because of the time and effort it takes to sort and identify them,” Portell said. “Harry has spent countless hours looking through a microscope picking through hundreds of thousands of pieces of shell hash, sorting out thousands of whole shells of 500 species. He imaged over a thousand of these fossils using electron microscopy and also identified the species, many of which are new to science, further enhancing the importance of this collection. His contributions are appreciated more than most people could imagine.”

Slapcinsky said he has benefitted personally from Lee’s help many times.

“While Harry has not been volunteering in the Malacology Division directly, he is a walking encyclopedia,” Slapcinsky said. “He is well versed in Latin, and is a fount of historical, taxonomic and other arcane knowledge which he shares generously. Harry also is a tremendous asset to the molluscan community, as he answers questions on molluscan listservs, judges shell shows, serves as editor and writer for the Jacksonville Shell Club newsletter, ‘The Shell-O-Gram,’ served as a board member for the Bailey-Matthews National Shell Museum (on Sanibel Island), and is a scientific adviser and contributor for the JaxShells website.

Lee is humble about the praise and receiving the Volunteer of the Year award, saying he is thankful to the museum for making his retirement entertaining.

“It goes without saying that I find working at the Florida Museum quite gratifying,” he said. “Working among dedicated and talented scientists gives one a sense of camaraderie and common purpose.”

Sources: Roger Portell, portell@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-2110;

John Slapcinsky, slapcin@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-1829

Learn more about the Invertebrate Paleontology Division