The Florida mouse and gopher tortoise have been in a serious relationship for thousands of years.

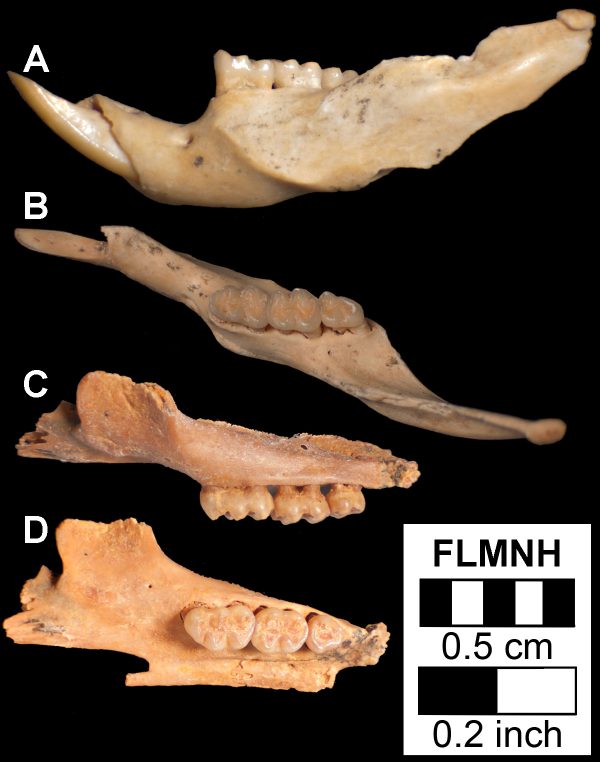

Florida Museum of Natural History photo by Natasha Vitek

Theirs is a commensal one: The Florida mouse uses the gopher tortoise’s burrow as shelter from the heat, but the tortoise gains nothing.

While the mouse also makes its way into other animals’ burrows, it tends to use the tortoise’s because of food availability and a stable microclimate.

Once a Florida mouse has found a gopher tortoise burrow, it will dig a side passageway or nest chamber off the main tunnel and make itself at home.

Research does not always support these relationships lasting over long periods of time. But a recent study conducted by museum researchers and published in the Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History revealed that these two species have been linked for at least 1.35 million years.

“I think this gives perspective that the relationship between the Florida mouse and gopher tortoise is special, and it’s been special for a while,” said Natasha Vitek, lead author of the study and a graduate student researcher at the museum. “It’s not a short-term thing that’s easily dissolved. There’s some strength and longevity in the relationship between these two species, and that may be worth preserving.”

Two awards from the National Science Foundation funded the study.

The researchers analyzed fossil records and examined 14 sites where Florida mice lived to see if there was evidence of gopher tortoises, finding the presence of fossils of both species at 12 of the sites.

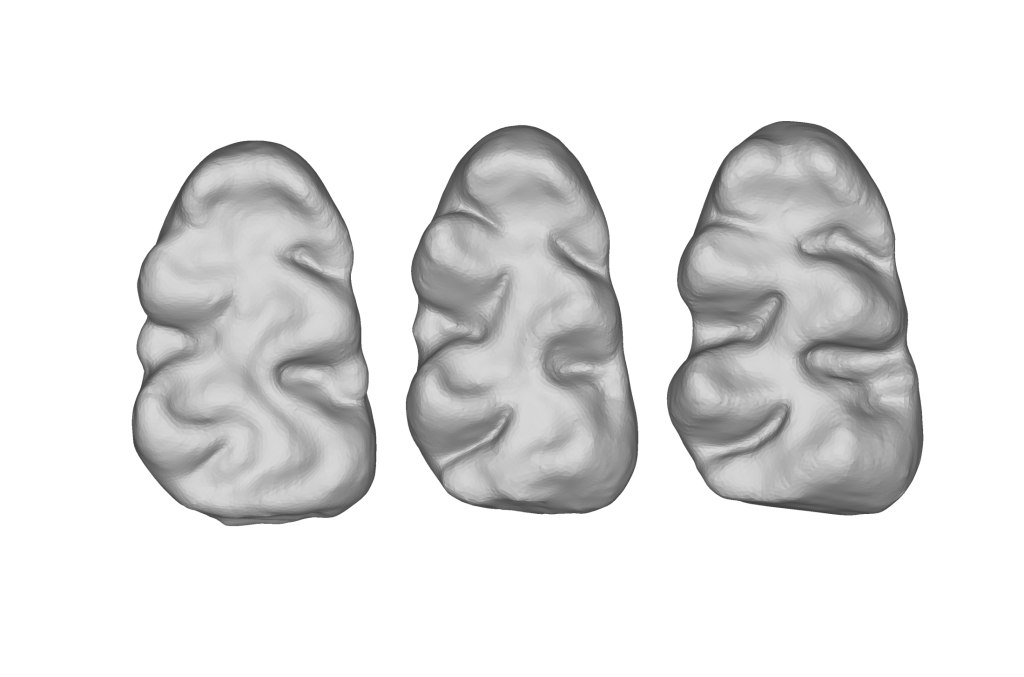

Vitek said she decided to conduct the study because she was already researching variations in Florida mice by examining their teeth.

“I had all that information in front of me, and I already knew they were associated with the gopher tortoise,” she said. “It wasn’t that far of a step to just do a few other searches for the gopher tortoise and other burrow associates, and the numbers were pretty straightforward.”

Vitek said this research could be applied to other species relationships, but it would be difficult to conduct the years of necessary background work, like collecting fossils, which was already completed for this study.

She said there are many benefits that can come from this kind of study, such as helping officials evaluate conservation priorities.

The gopher tortoise is an endangered species, but the Florida mouse is only listed as a species of concern. Vitek said this type of research can provide a better perspective on what’s in Florida today and help protect species by preserving historical species relationships.

Going forward, she said she would like to examine whether the form of the Florida mouse has changed over time. Currently only isolated teeth and parts of upper and lower jaws have been found.

“It would be interesting to see if — through that one and a half million years of history — we see the different shapes of teeth in the same frequencies in the fossil record, or were they changing?” Vitek said. “Is there evidence that even if there was this association, was the Florida mouse itself evolving? The gopher tortoise has already been studied a fair amount in the fossil record, so it’d be worth looking at that.”

Download the full study from the Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission biologists filmed these Florida mice scampering inside a gopher tortoise burrow.

Source: Natasha Vitek, nvitek@ufl.edu

Learn more about Vertebrate Paleontology at the Florida Museum.