Cover design by Terri Sirma and image by Juan De Cosa

A new book co-authored by a Florida Museum researcher examines the rich and distinct histories of the Caribbean islands before the arrival of Europeans and presents findings from the first excavation of a Carib culture site.

In “The Caribbean before Columbus,” Florida Museum of Natural History Caribbean Archaeology Curator William Keegan and Corinne Hofman, a professor of Caribbean archaeology at Leiden University in the Netherlands, detail Caribbean island societies from about 5,000 B.C. to the A.D. 1600s, offering what Keegan called the “most comprehensive” look at their pre-Columbian history.

“Islands seem to be unique places because the land area is of set size, and so we often see changes in human behavior and practices much quicker than in larger, continental areas,” Keegan said.

Other books on Caribbean history discuss island populations during Christopher Columbus’ time, but Keegan said now that more data is available, it was important to write a book that considered the lives of natives before Columbus arrived.

“I hope readers will get a better appreciation for not only the earliest inhabitants of the islands but also how people share in this history,” Keegan said. “The Old World and the New World were separated for so long, and our combined history really begins in the Caribbean. This book marks the beginning of world history as we know it today.”

Keegan and Hofman combined data from their archaeological digs over the past decade to write the book, including information on the first Carib excavation site.

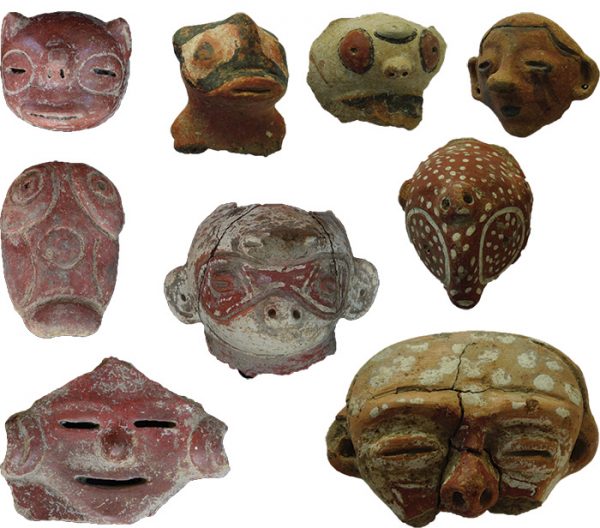

Photo courtesy of Corinne Hofman and Menno Hoogland

The scientists found the ways the islands, including the Bahamas, Guadalupe, St. Lucia, Martinique, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico and others, changed from the period when people first inhabited them to the decades following the arrival of Europeans.

Some of the findings surprised the archaeologists, who together have about 80 years of experience researching the history of Caribbean societies. Keegan said a common previous theory was that settlers traveled from South America to Puerto Rico by island-hopping through the Lesser and Greater Antilles. But Keegan and Hofman found many settlers traveled through the Caribbean Sea directly to some of the larger islands.

“That’s something that goes completely against what we would have expected and what everyone believed for the longest time,” Keegan said. “It also provides evidence of strong ties from the Caribbean islands to lower Central America.”

Keegan said many misconceptions about Caribbean societies existed because the natives did not have written records, while European settlers documented their observations.

“A lot of people were trying to fit the data to the Spanish reports because there was greater access to that information,” he said. “But we’re seeing that the two don’t match.”

Photo courtesy of Corinne Hofman and Menno Hoogland

For example, Keegan said, Caribbean societies were often thought to have been chiefdoms, but many of their societies were more tribal rather than headed by a single person.

“I think part of that is due to the Spanish, who expected to deal with a leader,” Keegan said. “They might invade the town and ask for the governor, but they don’t have that same title in their own culture, so there’s a lot of miscommunication with the Spanish.”

Natives also played a significant role in changing the landscape—burning forests to clear land, cutting trees for shelter and hunting island game.

“One of the things we looked at were the environments in which sites were located and how those have changed over time through things like deforestation, sea level change and volcanic activity,” Keegan said. “Some of the turtles we excavated at one site weighed more than 600 pounds, but others we found later at that same site were 60 pounds. So the natives affected the local environment more than people ever anticipated.”

Photo courtesy of Corinne Hofman and Menno Hoogland

These changes illustrate the importance of small islands’ development into economic and political centers for groups of people, Keegan said. Like Charles Darwin, he views islands as “laboratories,” physically separating people groups from one another and giving rise to distinct identities. These small-scale nations can offer insight into historical continental development.

“The Caribbean islands are a good model for how things happen throughout the world—how societies adapt to and change local conditions and the consequences of those conditions.” Keegan said. “One of the points that I’ve made in other publications is that mainlands are really composed of a lot of different islands. On a mountaintop, you’ve got the barrier of going uphill. On an island, water is a barrier, but for a lot of people, the sea was a highway and it was relatively easy to get to one place from another.”

“It’s a matter of perspective,” he said.

“The Caribbean before Columbus,” published by Oxford University Press, is available now in print, online and electronically.

Learn more about Caribbean Archaeology at the Florida Museum.