While some might press flowers into books to preserve their beauty, researcher Mark Whitten does it to preserve history.

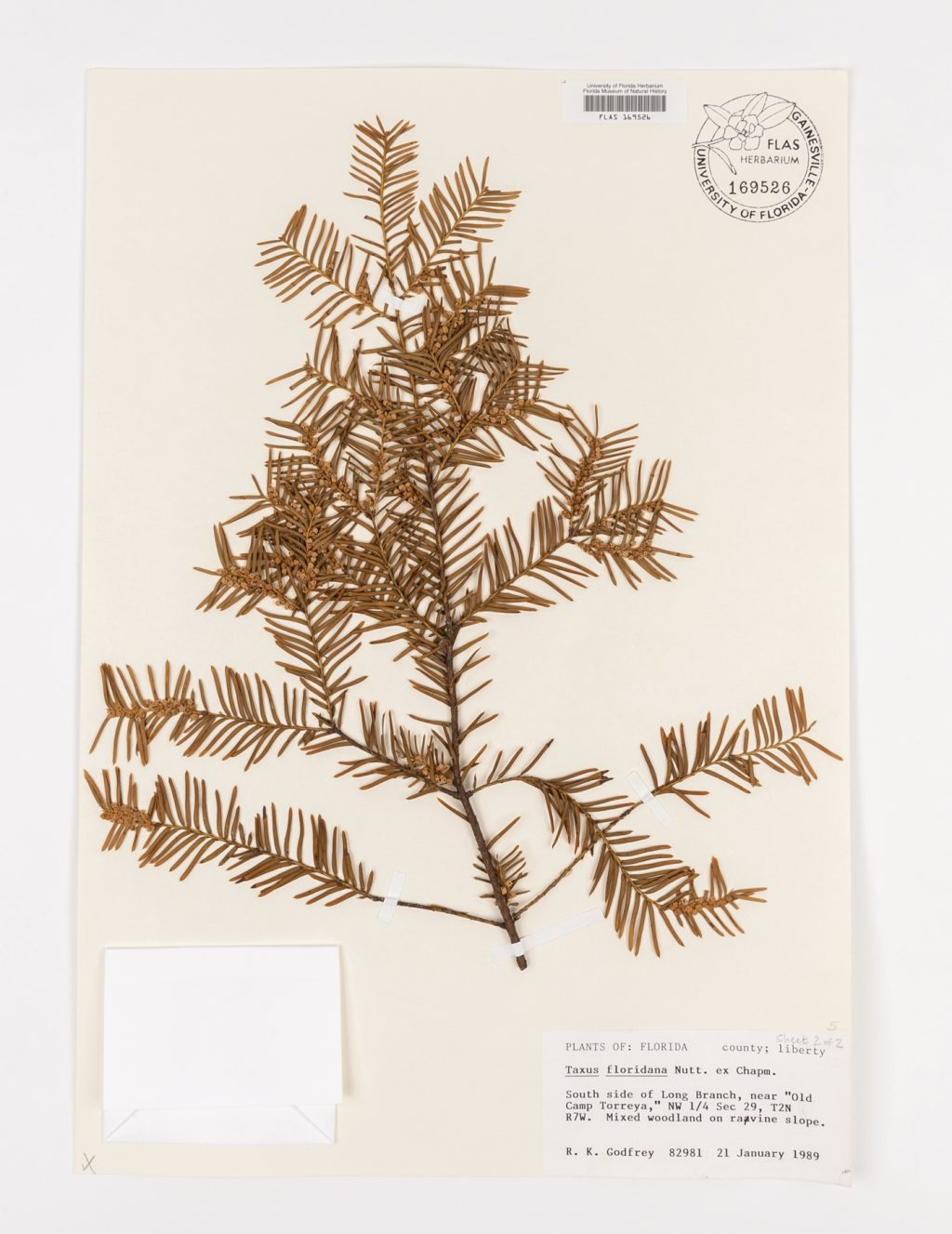

Whitten, a botanist in the Florida Museum of Natural History Herbarium, glues pressed plants onto archival paper and stores them as specimens in the museum’s collection.

He said herbarium specimens show data about plants’ location, habitat, flowers and fruits at the time of their collection. With this information, researchers are starting to make connections about recent climate change and its influence on the seasonal cycles of plants, or plant phenology.

Whitten said researchers lack good observational records on when plants start to flower, produce fruit or form leaves, which is where herbarium specimens come in.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

“If you get enough samples, statistically you’re going to be able to get a pretty good window on the flowering period of a plant,” he said. “And then you can correlate that with the temperature records of the site and ask the question: In 1880, were these plants flowering later or earlier than they are now?”

Whitten said shifts in climate, such as warming temperatures, can cause plants to flower earlier, before their pollinators are out, which prevents the plants from reproducing.

He said some studies, however, have shown that certain plants aren’t affected by changing temperatures.

“Some plants seem to not really ‘care’ what the spring temperatures are,” Whitten said. “Whether it’s 50 degrees or 80 degrees, they’re not going to flower until the day length reaches a certain number of hours.”

Pam Soltis, a distinguished professor and curator at the museum, worked with colleagues to produce a review paper in Trends in Ecology and Evolution on how herbarium specimens can be used to predict the effects of climate change on plant phenology.

“Some species may have the potential to move northward because that’s where the best climate will be for them in the future,” she said.

Soltis has found that comparing data from the past to the present can help determine future patterns in plant behavior.

“Even in Florida, we’ve seen over the last 60 years or so a pattern where species have responded to warming and drying climates in ways that we predict are going to happen into the future,” she said in reference to some of the Florida Museum Herbarium specimens.

Although dried herbarium specimens preserve many plant features, including DNA, only keeping them pressed to paper makes it difficult for many people to access the information they hold. Soltis said this is why digitization of data is growing rapidly. Digitization helps make all of the Florida Museum’s specimens globally available, which in turn fosters collaboration with other museums.

“There are more and more data available all the time from collections around the world,” she said. “(Digitization) has all happened just in the last six or seven years, so it’s just amazing to see what’s happening and how quickly. It just opens up all kinds of additional research.”

Whitten said the process of digitizing the Florida Museum’s herbarium collection is ongoing, with about 50 percent of the collection digitized to date and 30 percent available online.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

Charles Willis, an associate of the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University and a study co-author, said herbarium specimens are reliable sources of data but remain largely untapped resources because many people only view them as tools for classification.

“It’s incredibly vital, because if we’re going to understand how climate change is going to impact not just biology in general, but specific communities, we need to know how those individuals in those communities are going to respond,” he said.

Willis said he has only found about 30 studies that examined a few hundred thousand specimens of the millions found around the world.

“We just wanted to bring attention to the community that this is possible, that we can use these specimens for more than just classic taxonomic studies,” he said. “It’s really up to the community now to figure out new and novel ways to do research with herbarium specimens.”

Going forward, Soltis said looking at phenology with the help of herbarium specimens is important because they can help identify which land to conserve for the future.

“I think it’s a really critical time for us to use whatever sorts of resources we have available, and this is a relatively new set of data,” she said. “As we predict future distributions, we can see if a group of species might respond to climate change in the same way. If so, we can possibly use this information to set aside land areas for future conservation. Maybe we don’t necessarily want to preserve only where species occur now, but we might want to think about where they will exist in the future.”

The paper is the result of a workshop sponsored by iDigBio in March 2016.

- Learn more about the Herbarium at the Florida Museum.

- Listen to the stories behind the Museum’s Florida yew and orange blossom specimens.

- Learn more about the Soltis Lab at the Florida Museum.