Perhaps you have worn a string of pearls around your neck, paid for a diver to retrieve what you hope is a lucky shell or recognize these lustrous gems as your birth stone. But have you ever wondered where these iconic minerals come from, what makes a pearl a true pearl, and how a pearl can become a fossil?

We explored the backstory of pearls, with the help of Carmi Milagros Thompson, a University of Florida graduate student and a manager of the invertebrate paleontology collection at the Florida Museum.

What is a fossil pearl?

“As long as there have been mollusks, there have been pearls,” Thompson said. Over time, some of these pearls become fossils.

The oldest known fossil pearls are over 200 million years old, but pearls date back to the first appearance of ancient mollusks more than 500 million years ago. During fossilization, aragonite, the mineral that makes up a pearl, is replaced with calcite. A cross section of a fossil pearl will still show the concentric layering we see in modern pearls.

The Florida Museum has one of the top invertebrate paleontology collections in the U.S., estimated to contain more than 6.5 million specimens. It’s also home to an impressive collection of fossil pearls, Thompson said. Due to their rarity and unique appearance, fossil pearls can spark public interest in the field of invertebrate paleontology.

“They’re cool, beautiful and unique ways to inspire people about fossils,” she said. “But beyond that, they also have interesting stories to tell us when we look at them closely.”

How do pearls form?

Pearls form through two different processes: biological and environmental.

Though we admire pearls as gems, their biological formation is the result of a defense mechanism.

“We see something beautiful that’s actually an animal’s way of saying, ‘Hey, what’s going on here?’” Thompson said.

We most commonly associate pearls with oysters and sometimes clams, but they can come from nearly any mollusk, including some marine snails and even octopuses, though this is much rarer.

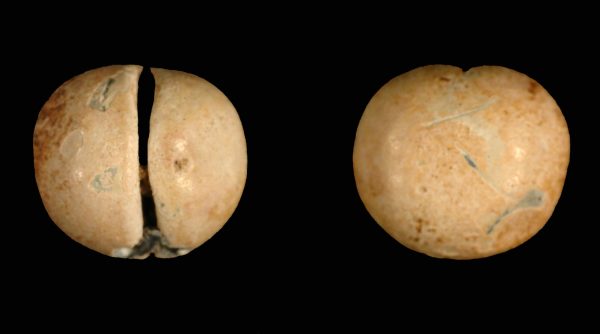

Florida Museum photo from the Invertebrate Paleontology Collection

While you may have learned that a pearl forms from a grain of sand, a variety of irritants can enter a mollusk and cause the formation of a pearl, including parasites, small fish or anything that disrupts cells in the soft inner body known as the mantle.

To deal with the irritant, some mollusks gradually coat it in layers of a smooth crystalline substance called nacre to seal it off. Nacre, also known as mother-of-pearl, is the same material that makes up the inside of some shells. Occasionally the irritant will enter the space between the mantle and shell, and the pearl will form in the nacre of the shell wall. These are called “blister pearls” and can also be found in the fossil record. Other mollusks will simply coat the irritant with aragonite or calcite.

How can a cave make a pearl?

The less common way pearls are formed is through environmental processes in limestone caves, such as those found in Florida.

“When people think of caves, they think of stalagmites and stalactites. They don’t think a pearl could form in this environment because usually they think of pearls in a marine environment,” Thompson said.

Cave pearls form when a nucleus – such as a grain of sand – is exposed to moving water in a carbon dioxide-depleted environment. As the cave precipitates calcite, it coats the nucleus in concentric layers, just like those of a biologically-formed pearl.

When an artificial material is coated in calcium carbonate, it can look like a pearl, but it’s an example of what scientists refer to as “pseudo pearls.” The museum’s invertebrate paleontology collection contains a pseudo pearl that was formed around a pinch-on sinker fishing weight.

Florida Museum photo from the Invertebrate Paleontology Collection

Where can you find fossil pearls?

Finding a pearl is rare enough. With the added factors of time and fossilization, you can imagine how rare and exciting it is to find a fossil pearl. Fossil pearls can be found loose, while “blisters” are sealed inside fossilized clams.

Fortunately, “Florida is a great place to find fossil pearls,” Thompson said.

Because Florida was underwater for most of its history, marine fossils can be found throughout the state. Most of the well-preserved mollusks and pearls found in Florida are in fossil sites from the Plio-Pleistocene to the Miocene Epoch, dating back about five million to 23 million years ago.

“Anything older than that is mostly just the impressions mollusks left. In theory you could find pearls in these older units, but you would have to put in a good amount of time,” Thompson said.

If you want to learn more about Florida fossils and their history, visit the museum’s “Florida Fossils: Evolution of Life and Land” exhibit, which showcases many fossils found within 100 miles of Gainesville.

What’s up with “cosmic pearls,” and are they even pearls?

“Cosmic pearls” are not pearls at all, but microtektites, small particles that form in response to the impact of extraterrestrial objects such as meteorites.

The museum has an interesting history with cosmic pearls. Dozens of microtektites in the museum’s collection were originally discovered in 2006 by University of South Florida undergraduate Mike Meyer, who was searching for tiny fossils in a Florida quarry that offered a cross section of the last few million years of the state’s geological history. When he first discovered tiny glass-like orbs, no bigger than a grain of salt, he didn’t know what they were. It was not until years later that Meyer solved the mystery by analyzing the elemental makeup.

Despite the fact that these cosmic pearls were found inside fossilized clams, they are not the product of invertebrates and are not true pearls.

Thompson said this story isn’t just fascinating, but inspiring as well: Meyer was an undergraduate when he made this novel discovery, showing that “anyone can make big contributions to our field if they are curious, want to ask questions and put in the time – not just people with a Ph.D.”

Source: Carmi Milagros Thompson, cthompson@floridamuseum.ufl.edu