Key Points

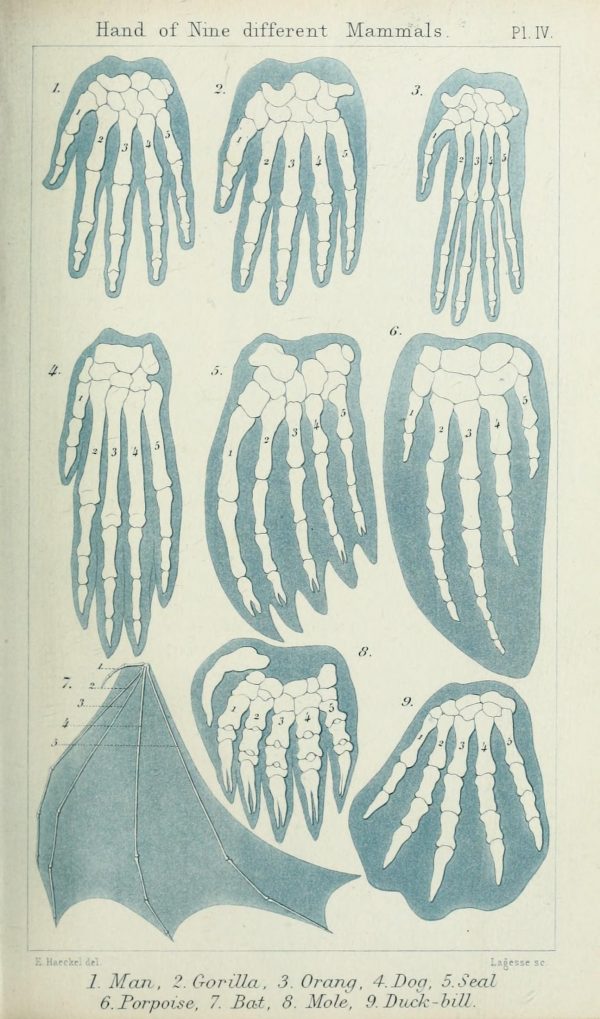

- Convergent evolution occurs when completely unrelated groups of animals evolve similar features in response to similar environmental pressures. A classic example is the evolution of flippers in reptiles and mammals that returned to life in the water millions of years after their ancestors voyaged onto land.

- Using a statistical method originally developed during World War II, scientists found that by measuring an animal’s forelimb proportions they can reliably predict if an animal had flippers but not whether they had webbing between their toes.

- They used this information to determine whether extinct species were predominantly aquatic or terrestrial. The results allowed them to chart a more comprehensive evolutionary history and clarify the lifestyles of several long-debated animal groups.

O

ver 370 million years ago, early ancestors of today’s reptiles and mammals crawled out of the water onto land. Since then, many of their descendants have independently returned to the ocean, evolving remarkably similar solutions for their new lives underwater. Scientists have tried to tease apart when and how these transitions occurred by measuring the shapes of fossils to infer whether extinct animals were using their limbs to swim in the water, walk on the ground or do some combination of both, but the results haven’t always been reliable.

In a new study, paleontologists have put these measurements to the test and used the results to map out millions of years of evolutionary history.

“To me, one of the most remarkable things in biology is convergent evolution, which is when completely unrelated groups of organisms evolve similar features in response to similar environmental pressures. The mammals and reptiles that returned to aquatic lifestyles are a perfect example of this, because they all had to change their land-adapted limbs in similar ways to handle the fixed physical challenge of moving around in the water,” said lead author Caleb Gordon, who conducted the research at Yale University and recently joined the Florida Museum of Natural History as a postdoctoral researcher.

Land dwellers that returned to the water had to change everything from the way they held their breath and moved to what they ate and how they sensed their surroundings. In particular, the arms and legs of these animals changed in ways that helped them move more effectively through the water. Species that live exclusively on land or in water, such as horses or whales, have skeletons that are straightforward to interpret. But those that spend some blend of time on land and in the water have fossils that are more ambiguous.

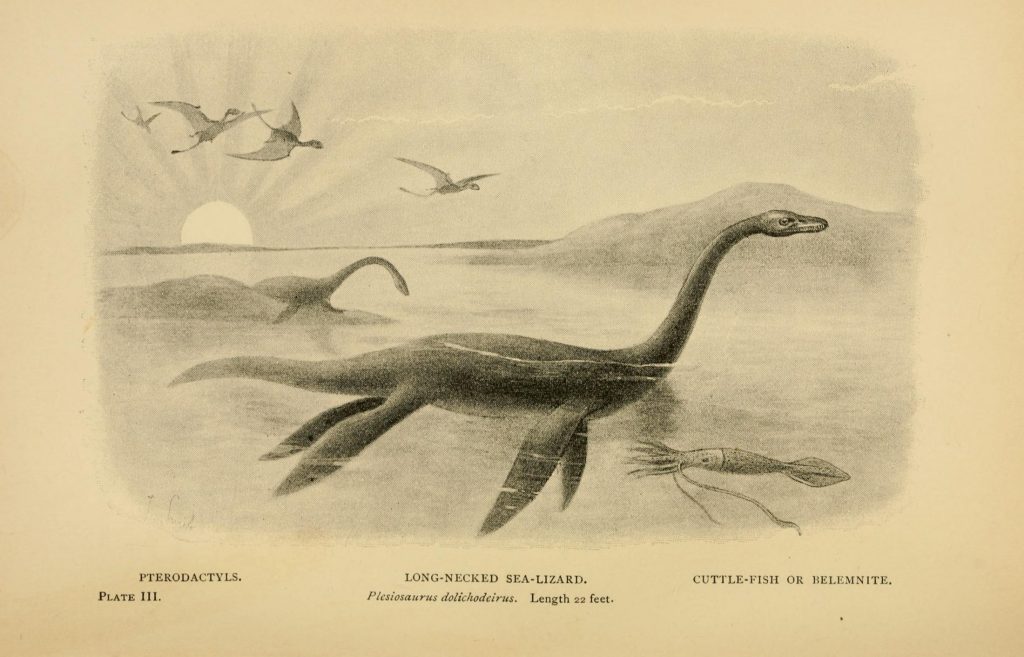

Illustration from "The history of creation, or, The development of the earth and its inhabitants by the action of natural causes : doctrine of evolution in general, and of that of Darwin, Goethe, and Lamarck in particular" (1876)

“A lot of species fall into this ambiguous category, and understanding which of them first committed to spending the majority of their time in the water is critical for understanding when, how and why these land-to-sea transitions took place,” Gordon said.

Paleontologists have often used the presence of soft-tissue features, like webbing between the fingers and flippers, to figure out how aquatic an animal was, but soft tissues like these rarely make it into the fossil record. Instead, paleontologists rely on the shape of an animal’s bones to determine whether it evolved for swimming or moving on land. In the past, they used features like the symmetry of hands or feet, the length or width of fingers and toes, and the proportions of the limb segments to place animals along a spectrum of fully terrestrial to fully aquatic.

“But the connection between these skeletal features and webbing or flippers, and the connection between webbing, flippers and aquatic habits, hasn’t been carefully evaluated in enough species for us to know if these connections actually hold up scientifically,” Gordon said.

Sometimes these skeletal features even contradict each other. In a single animal, measuring one aspect of the bone might indicate it lived mainly on land, but measuring a different aspect might indicate that it was fully aquatic.

Before conducting his own analysis of how aquatic habits evolved in these groups, Gordon needed to start with the basics and determine which measurements were the most reliable. He visited museum collections across the northeastern United States to measure the limb bones of both modern and extinct species. For specimens farther away, such as the several specimens in his study housed at the Florida Museum of Natural History and available through the openVertebrate initiative, Gordon relied on digital 3D scans and photographs. Using physical and digital data sources, he gathered over 11,000 measurements from nearly 800 specimens, spanning the range of full-time land dwellers to fully aquatic animals and everything in between.

“Projects like this only work when you have museums that digitize and share their specimens with researchers,” Gordon said. “Without accessible natural history collections, research like this wouldn’t be feasible, and the evolutionary histories of our ancestors would be forever unknown to us.”

While collecting these measurements, Gordon saw for himself the contradictory nature of some of these specimens.

“In some fossils, I would notice that the relative lengths of the hand and the lower arm of a species were really similar to those of other aquatic species, but the measurements of the bone at the tip of the finger were more similar to those of other terrestrial species,” Gordon said. “In order to interpret these results in a way that could address these inconsistencies, I needed a new, transparent analytical pipeline for choosing which line of evidence to believe when they disagreed.”

That was when, in a moment he called “serendipitous,” Gordon came across something called receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis.

“ROC analysis is a cool, almost steampunk statistical technique that was developed by the U.S. Army Signal Corps in World War II,” Gordon said. “It has been used since the 1950s in psychiatry, biomedical research and military research where stakes are really high. But for some reason, it hasn’t been used much if at all by paleontologists — even though it’s exactly what we need.”

During World War II, the Signal Corps relied on radar signals to detect and determine the allegiance of incoming aircraft, but the signals were not always clear. Operators needed a way to identify enemy planes without mistaking them for friendly aircraft or interpreting background noise as threats. But some signals had conflicting characteristics that pointed to mixed conclusions. To make decisions in these cases, the Signal Corps engineers developed a new modeling approach to determine which of these characteristics was most accurate in predicting a plane’s allegiance. And receiver operating characteristic analysis was born.

“ROC analysis compares how well different observed characteristics, be they radar signals or skeletal features, tend to classify an unknown object. The U.S. Army Signal Corps used ROC analysis to classify incoming planes based on radar signal characteristics. I figured I could use it to classify extinct mammals and reptiles based on skeletal characteristics,” Gordon said.

It was the solution Gordon was looking for: a way to choose which bone measurement to use when multiple measurements disagreed. Using ROC, he analyzed the measurements he collected on modern animals to determine which one was the most accurate in predicting whether that animal spent most of its life in the water.

Photo Courtesy of Caleb Gordon

Some measurements were indeed better than others. There was no clear connection between any skeletal features and whether an animal had webbed feet, but one feature did hold up for predicting aquatic habits: the ratio of hand length to lower-arm length. With this measurement, Gordon was able to identify whether an animal had flippers and spent most of its time in the water with over 90% accuracy.

“If you look at the skeleton of most of these aquatic animals, most of their arm is just a giant hand because the other bones are so small. And they wrapped this big, thick blanket of soft tissue around the lower arm and hand to make it one continuous surface. Doing that allowed them to swim more efficiently,” he said.

Using this relative hand length measurement, Gordon fed his data on modern and extinct animals into a model to generate evolutionary trees, tracing when different animals developed flippers and highly aquatic habits through time.

He and his co-authors found that, throughout their evolutionary history, the ancestors of today’s reptiles seemed to be better at evolving flippers than those of mammals. Their flippers are often longer-handed, and they evolved more often. Previous studies have suggested that mosasaurs, giant seafaring lizards, evolved flippers on at least two separate occasions, and this study confirmed it.

This tendency to evolve flippers may partly explain why reptiles recovered more quickly and invaded the oceans after an extinction event known as the “Great Dying” wiped out the vast majority of Earth’s animal species 252 million years ago. While they developed flippers and aquatic lifestyles, the ancestors of today’s mammals, who were thriving on land before extinction, didn’t commit to life in the water until over 180 million years later.

The study’s results also shed light on some more ambiguously aquatic fossils, clearing up some ongoing debates in paleontology. All the semiaquatic reptiles that lived before the age of the dinosaurs, some 304 to 252 million years ago, are one example. Despite some characteristics of their bones and life histories pointing toward fully aquatic habits, the analyses show that all known semiaquatic reptiles of this period, including the disputed mesosaurs and understudied Spinoaequalis, regularly ventured onto land.

Perhaps most famous is the contentious case of the Spinosaurus, a large meat-eating dinosaur that lived from about 113 to 93 million years ago in what is now North Africa. Once thought to be a land-walking predator resembling a Tyrannosaurus rex, the dinosaur has undergone several reinterpretations as new fossils and isotopic evidence emerge. Looking at the shape of the skeleton, some scientists have described it as a primarily terrestrial fish-eater, like an oversized heron wading along the shoreline and catching fish. But Spinosaurus bones are also very dense, similar to penguins and other vertebrates that spend a lot of time diving in the water. Gordon’s work with forelimb measurements has shown that Spinosaurus likely spent most of its time underwater, backing up the idea that these dinosaurs may have been adept swimmers that hunted beneath the water’s surface.

For paleontologists studying other evolutionary questions, this new method could serve as a useful starting place. Any paleontologist can pick up a fossil, take a few measurements and plug them into the model to determine how aquatic the animal was. Or they can substitute different traits to predict different behaviors, like whether dinosaurs flew or ate large prey. The method remains the same, but the variables change.

“Nearly any prediction you want to make in the fossil record, you can make with this method,” Gordon said. “It could help pave the way for bigger, broader questions about the history of life on Earth or uncover things that were previously hidden or mired in disagreements because of conflicting lines of evidence. In this way, I think it can resolve a lot of disputes in paleontology.”

The study was published in Current Biology.

Lisa Freisem of Yale University; Christopher Griffin of Princeton University; and Jacques Gauthier and Bhart-Anjan Bhullar of Yale University and Yale Peabody Museum are also co-authors of the study.

Funding for the research came from the National Science Foundation (grant no. DGE1752134), the Yale Institute for Biospheric Studies and the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group.

Source: Caleb Gordon, calebgordon@ufl.edu

Writer: Brooke Bowser, bbowser@floridamuseum.ufl.edu

Media Contact: Jerald Pinson, jpinson@floridamuseum.ufl.edu, 352-294-0452