Over the course of four weeks this summer, a motley crew of biologists, engineers, entrepreneurs and programmers gathered at predetermined sites within Windsor Nature Park, a 185-acre tropical rainforest located in the heart of Singapore. They’d traveled from all over the world to participate in a one-of-a-kind competition hosted by the XPRIZE Foundation, in which 13 teams would have three days to identify as many organisms within the forest as possible.

Up to 10 winning teams would equally split $2 million and advance to the 2024 finals, where they’d vie for the first-place prize of $5 million. But there was a catch: All observations and data collection had to be conducted remotely.

“The competition is specifically intended to spur the development of technology that allows us to monitor biodiversity within rainforests without disturbing the ecosystem,” said Niyomi House, a National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellow with the Florida Museum of Natural History.

House is a member of Team Waponi, which is led by Thomas Walla, a professor of biology at Colorado Mesa University, and is one of the few groups that made it to the semifinals in Singapore this summer. After a delay in which judges tallied the number of species and verified identifications, XPRIZE recently announced that Team Waponi is among the six finalists and will compete next year in Brazil’s Amazon Rainforest in the state of Amazonas.

The winning device that secured the team’s place in the finals involved a wireframe box, a drone and a saw.

“Our team invented a device called the Limelight, which attracts insects in the forest canopy,” House said. On the morning of June 3, members of Team Waponi carefully assembled their equipment and waited for noon, which would mark the start of the 24 hours they’d have to collect data.

When the clock started, drone operators piloted five Limelight devices into the canopy, gently placing each into the bough of a tree. As the sun descended, bulbs attached to the frame flicked on, illuminating a white canvas that served as both beacon and landing pad for insects attracted to the light. Cameras on either end of the screen photographed each visitor. Above this stage, a malaise trap captured insects as they flew upward, while an inverted pit trap below caught insects attempting to crawl away.

A third trap was stocked with a pungent lure to attract dung flies and an additional camera to photograph them. The Limelight devices were also equipped with bioacoustics recorders. The team was counting on these digital eyes and ears to detect more than members could with their own senses.

Before navigating back to the group, the drones collected plant samples using an extendable saw. The team’s time was cut short by five hours because of storms that dropped thick sheets of rain, during which the drones couldn’t operate. But when the skies cleared and the Limelights were retrieved, the devices were filled with hundreds of insects. That’s when the real work began.

“Each team had 48 hours to extract and sequence DNA, analyze the results and write a report,” House said. “The experience felt like completing an entire master’s degree in just two days.”

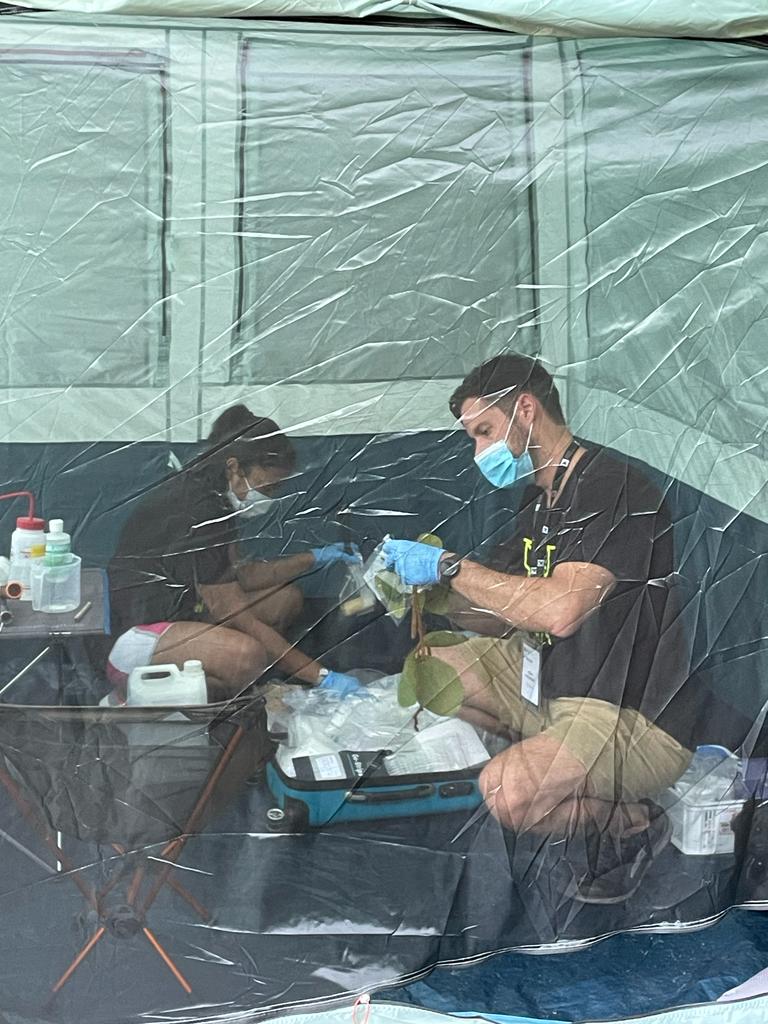

House and her teammate set about gleaning as much information as they could from each specimen, splitting their time between a field lab set up in a tent and a molecular lab at the nearby National University of Singapore.

Meanwhile, other members of the team ran each photograph through machine learning software, which identified insects based on their physical characteristics. A similar program was used to single out the various hoots, howls, caws and grunts captured by the bioacoustics monitor and match them to those of prerecorded animals.

When they added everything together, the team members had collectively identified hundreds of species, genera and families, all without stepping foot in the forest. The speed at which they could strip living things down to their component DNA base pairs and use that to decipher the identity of the organism they belonged to was a physical and technological feat.

“The way it’s currently done, the process of DNA extraction, amplification, cleaning and creating a genetic library is not easy. There are several reagents that have to go in at different times with specific temperatures, and it takes hour and hours of training to learn how to do it,” House said.

The main goal of the XPRIZE competitions is to test and extend the limits of existing technology. The foundation got its start in 1996 with a $10 million prize for the team that could design a suborbital aircraft capable of flying into space.

A few years ago, it would have been impossible to identify organisms across an entire ecosystem with ambient noise and trace amounts of DNA. Team members are in the process of adding even more bells and whistles to the Limelight before the competition’s final round, but regardless of the outcome, they intend to continue developing techniques that make biodiversity science and monitoring more accessible to everyone.

“My dream is to eliminate the complexity of DNA sequencing by creating a set of standard tools and kits people can use in different situations and a pipeline that tells them what’s available and how to access it,” House said.

Source: Niyomi House, nwijewardena@ufl.edu

Writer: Jerald Pinson, jpinson@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-294-0452