A new study on louse evolution shows the parasite’s genetic structure differs based on geographic region, information essential for developing more effective insecticides.

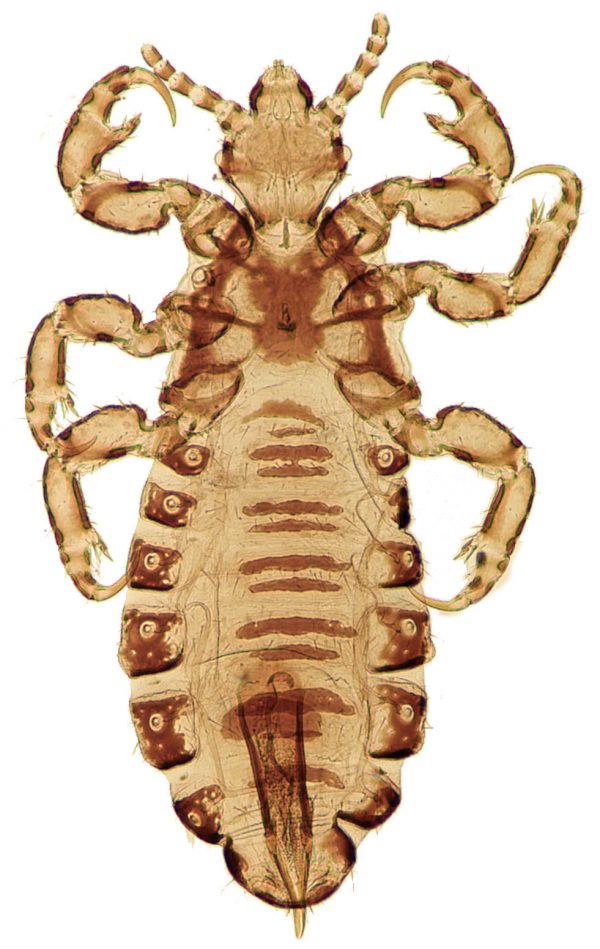

Florida museum photo by David Reed

Hundreds of millions of head louse infestations affect children worldwide every year and numbers continue to rise, partly due to resistance to insecticidal shampoos. The study appearing online in the journal PLOS One today is the first to analyze nuclear genetic variation of head lice, providing a more complete evolutionary history of the parasite. Understanding genetic structure worldwide allows researchers to make insecticides tailored to a particular population, because control methods effective in one region may not be successful in others.

“Insect populations will develop resistance to insecticides in different ways and to create an effective management plan, you need to take into consideration the genetic profiles of these populations,” said lead author Marina Ascunce, a postdoctoral associate with the Florida Museum of Natural History on the UF campus. “If these populations have high gene flow, you may need to apply a different treatment than if you have populations that are not migrating among each other.”

The two-year study is part of a long-term project to better understand human evolution and migration patterns throughout history, such as the possible interaction between Neanderthals and modern humans, Ascunce said.

“The nucleus is really telling us the history of the species as a whole,” said Ascunce, who is also affiliated with UF’s biology department. “It’s a very host-specific parasite and this is telling us we can compare lice with human genetic data.”

Researchers analyzed nuclear genetic variation in 93 human lice from 11 sites in four regions: North America, Central America, Asia and Europe. Using 15 newly developed microsatellite loci, or molecular markers, which identify a particular sequence of DNA, scientists discovered the genetic variation of head lice is greater than expected, Ascunce said.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

“When we started this project, we thought, ‘Well, humans move all over the globe like crazy,’ ” Ascunce said. “However, this doesn’t impact the genetic structure of the lice, because you get different genetic structures for each geographic region. For example, a louse from Europe will have a genetic profile that is different from a louse from Central America.”

In the analysis, lice were grouped into genetic clusters to see which geographic populations were most closely related. Unexpected similarities were seen in lice from distant locations, Ascunce said.

“Geographically, the U.S. and Honduras are closer together, but genetically, Honduras is closer to Asia,” Ascunce said. “This is showing us that the lice from Honduras were probably brought from Asia when the first people arrived in the Americas.”

Lice from New York showed similarities with those from the United Kingdom and Norway, while lice from Nepal seem to be in between those from Canada and Cambodia.

Because previous research had only been mitochondrial, the study is a good first step toward understanding the nuclear and genomic-wide diversity of lice, said molecular anthropologist Drew Kitchen, an assistant professor at Iowa State University, who was not affiliated with the research.

“The structure of head lice around the world seems to match the structure of human populations, as well,” he said. “That further affirms the co-evolutionary history of human head lice and human populations.”

The study also includes analysis of clothing lice from Canada and Nepal, showing there may be gene flow between clothing and head lice. Study co-authors hope to continue this analysis because clothing lice make bacteria linked to certain diseases, including typhus, trench fever and relapsing fever, Ascunce said. More than 50 researchers worldwide collect and send lice to the Florida Museum of Natural History for the project.

“We really need to understand if there is gene flow between clothing and head lice and how that could potentially represent a risk of epidemic diseases in head lice,” Ascunce said. “One of these bacteria was recently found in head lice in Nepal, the U.S. and Ethiopia.”

Study co-author David Reed, associate curator of mammals at the Florida Museum of Natural History, is the project’s principal investigator. Other co-authors include Melissa Toups of Indiana University, Gebreyes Kassu and Jackie Fane of UF and Katlyn Scholl, all previously with the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Learn more about the Mammals Collection and the Reed Lab at the Florida Museum.