Every year, the Florida Museum’s Department of Natural History awards funding for University of Florida graduate students to help cover the cost of travel associated with their research. After a long year of travel restrictions, the funds were especially helpful to this year’s recipients, many of whom had to scrap plans, delay work and shift to other research priorities in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

When the spring semester let out earlier this year, award recipients set out to make up for lost time. Shelly Gaynor, a doctoral candidate in biology, used the funds to trek through the southern Appalachians in search of beetleweed, Galax urceolata, a small evergreen shrub with a perplexing origin story.

Photo courtesy of Shelly Gaynor

Although considered a single species, beetleweed populations differ in the amount of DNA they contain. Some are normal diploids, with a set of chromosomes from each parent, but other populations can have plants with a complement of three and even four chromosome copies, a phenomenon known as polyploidy.

Despite their genetic differences, beetleweed often reproduces freely between populations, creating plants with varying amounts of DNA that look exactly alike, much to the chagrin of biologists trying to unravel the natural history of the species.

“It’s just a crazy mess,” Gaynor said. “It really got me questioning, ‘What’s going on here, and how can we differentiate it?’”

Although comparatively rare in animals, polyploidy is the norm in plants, in which it often confers a competitive advantage, allowing them to compete more effectively for resources or radiate into new environments.

“All that extra DNA might mean the difference between life and extinction for beetleweed and other plants in a warming climate,” Gaynor said. “A solid understanding of how genetic diversity is created in plants is thus an indispensable part of maintaining our food supply and conserving natural areas.”

Gaynor also relied on a small number of specimens stored in herbaria across the U.S., which she had shipped to the University of Florida Herbarium for DNA analysis. For biology graduate students Thomas Murphy and Alex Abair, a much larger proportion of the plants they needed for their projects had already been collected by other researchers. Murphy and Abair used their funding to visit these specimens in person, traveling to herbaria housed at universities and botanical gardens in several states, including New York, Arkansas and Wisconsin.

Photo courtesy of Thomas Murphy

“I always feel invigorated and inspired whenever I go to a large herbarium,” Murphy said. “It’s just a really good place to synthesize all the information people have been collecting for years.”

Murphy, who’s studying plants in the greenbrier family, worked extensively in the New York Botanical Garden over the course of nine days this summer, taking small snippets of leaves from preserved specimens for later DNA extraction. While there, he also helped annotate out-of-date catalogue information for specimens collected decades ago, some of which have remained untouched since their initial collection and likely represent new species previously unknown to science.

“Many of them fall under the radar,” Murphy said. “They get lumped in with existing species that look artificially similar, but when you really look closely at multiple specimens, there are patterns that start to stand out.”

Closer to home, Tyler Bowling set aside a month to search for sharks along a small stretch of coast in New Smyrna Beach known as the shark bite capital of the world.

It’s very strange that this one little inlet in Florida would have so many shark bite occurrences, said Bowling, a biology graduate student and manager of the Florida Program for Shark Research. “These are very minor bites, but they are extremely frequent, often occurring in double digits each year.”

New Smyrna Beach is a tourist magnet. Just east of Orlando, the city offers a variety of beaches, parks and natural areas. It’s also one of the best places to surf along the Atlantic coast; water pouring in from two nearby jetties create a gyre, which churns up waves year-round. “It’s quoted as being the most consistent surf on the eastern seaboard,” Bowling said.

The same conditions that make the inlet a great place for people are also extremely favorable for marine life. The shallow, swirling water kicks up nutrients that transform the inlet into an ideal feeding ground for fish, which in turn attract a variety of predators, especially blacktip sharks, Carcharhinus limbatus. In a small area so highly trafficked by multiple species, encounters are bound to occur.

Photo courtesy of Tyler Bowling

Bowling hopes to determine which environmental conditions are the most closely linked with the presence of sharks, which can then be used to predict when the highest number of bites are likely to occur.

“The goal is to go out and acoustically tag these animals,” he said. “If we see any correlations to environmental patterns, we can get an idea of when sharks are more likely to move into the inlet.”

While most students travel separately to obtain data for their independent projects, others can pool their resources to address similar questions. This is especially true of paleontology, in which researchers often travel to the same dig sites, which turn up a variety of fossilized organisms.

“We all see the outcrop a little bit differently,” said award recipient Carmi Milagros Thompson, a graduate student in the Department of Geological Sciences studying marine invertebrates.

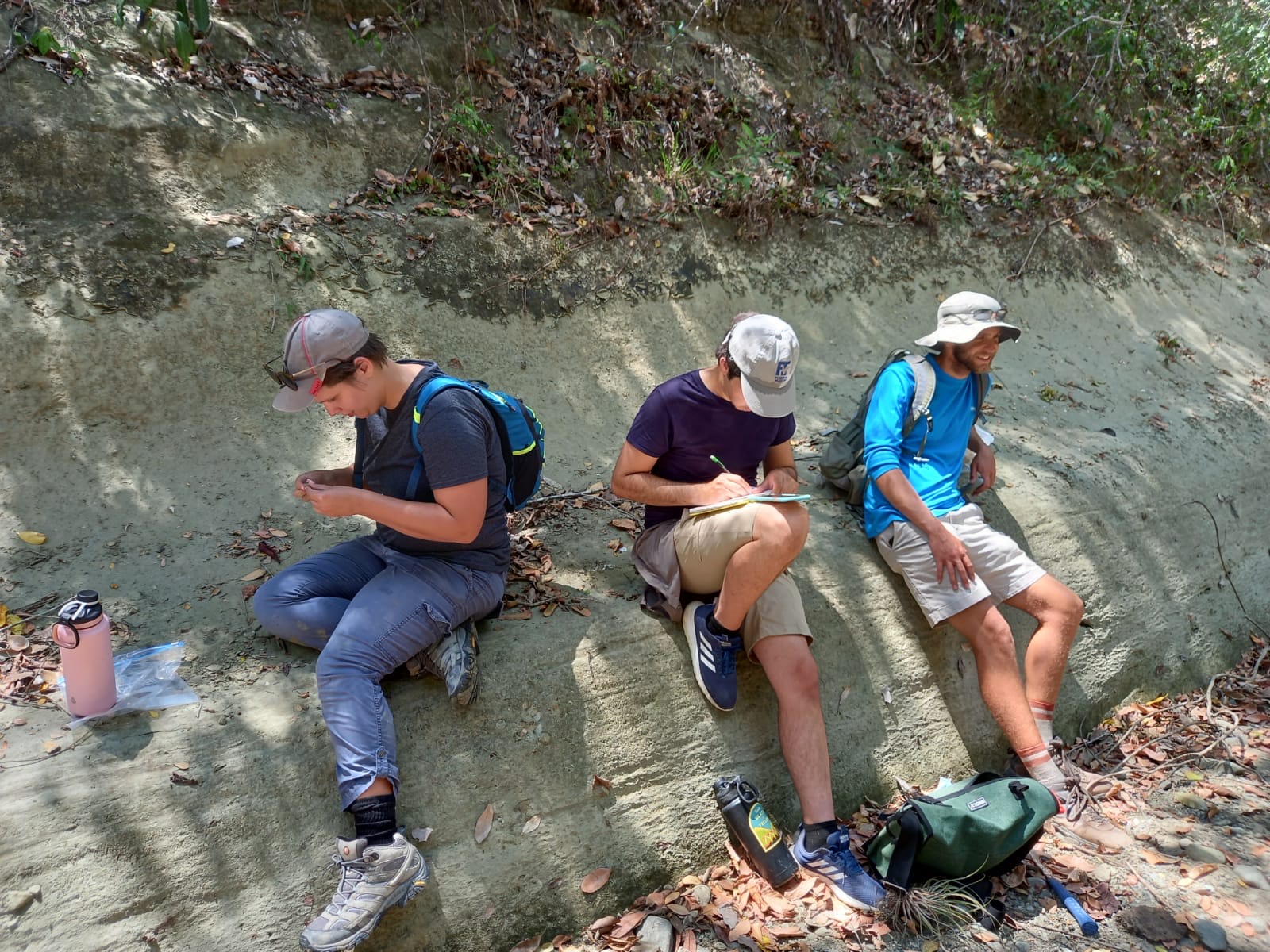

Thompson and biology graduate students Lazaro Viñola Lopez and Mitchell Riegler spent several weeks in the Dominican Republic. There, they worked closely with the curator of the paleontology, Juan Almonte, at the DR’s National Museum of Natural History to identify and catalogue fossils relevant to their research. They also visited several field sites to do some collecting of their own.

Photo courtesy of Lazaro Viñola Lopez

Viñola Lopez specifically focuses on extinct mammals that once inhabited the Greater Antilles and is broadly interested in how life in the Caribbean has changed through geologic time. But the fossilized remains of organisms that lived on land are incredibly rare in the tropics due to a combination of dense vegetation and conditions unfavorable for preservation.

For Viñola Lopez, it’s like trying to complete a puzzle with several missing pieces.

“We have very few Caribbean fossils, and the vast majority of those that exist are from the last 50,000 years,” Viñola Lopez said. “You might have a road cut or construction site, and you have a very short window to go in and collect fossils before the locality gets covered in vegetation.”

Viñola Lopez, Thompson and Riegler are currently in the process of analyzing their samples and plan to continue collaborating well into the future, each drawing strength from their various areas of expertise.

“Nothing exists in isolation,” Thompson said. “It’s really important to be exposed to different systems and methodologies outside of what you usually encounter and to learn from how other people conduct research, both to improve your own research and to see potential connections and collaborations.”

Graduate students Gregory Jongsma, Shelby Krupar and Julian Correa Narvaez were also recipients of the 2021 Summer Travel Awards.

Funds for the Florida Museum travel awards are funded in part by the Louis C. and Jane Gapenski Endowed Fellowship.

Sources: Shelly Gaynor, michellegaynor@ufl.edu;

Thomas Murphy, tmurphy1@ufl.edu;

Tyler Bowling, tbowling2@ufl.edu;

Carmi Milagros Thompson, cthompson@flmnh.ufl.edu;

Lazaro Viñola Lopez, lvinolalopez@ufl.edu

Writer: Jerald Pinson, jpinson@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-294-0452