A

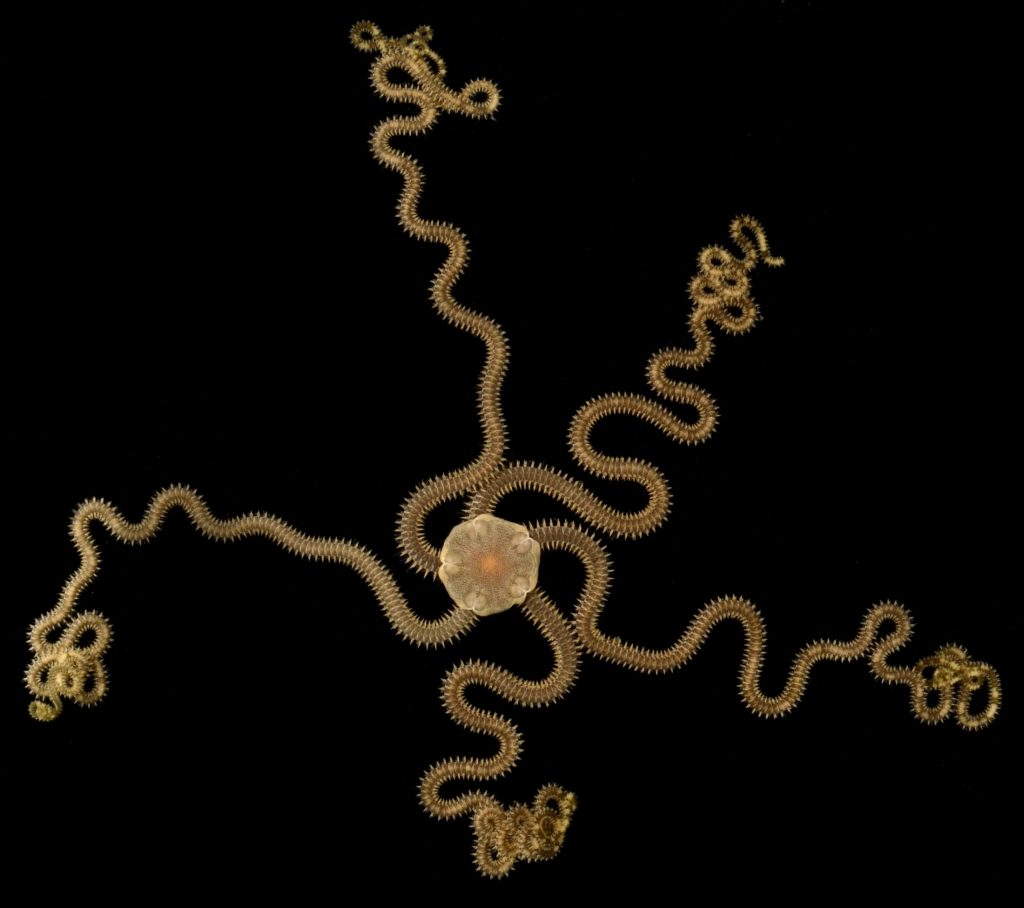

ncient, gangly cousins of sea stars, brittle stars crawl the seafloor on five flexible arms, which in some cases measure 2 feet long and can be shed and regrown at will. With no eyes, heart or brain, the spiny creature consists mainly of a central disk, which houses a stomach and mouth surrounded by five tooth-lined jaws.

“Brittle stars are great to work with. They have a skeleton, which is useful for identification. They are abundant, so you can find hundreds or thousands of them in an area. And they live in all parts of the world’s oceans,” said Gustav Paulay, curator of invertebrate zoology at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Ancient, diverse and abundant, brittle stars boast a winning combination that has made them the subject of decades of research, filling museum shelves around the world. In a new study published in Nature, scientists analyzed and compiled these samples into a global dataset that offers a holistic view of their evolutionary journey across the seafloor. Their findings reveal that brittle stars have spent millions of years steadily migrating across the world’s oceans, and their deep-sea network shows that life in the depths is more connected than one might expect.

Ranging thousands of miles from the equator to the poles and plunging from shallow coastal waters to deep-sea trenches, brittle stars are everywhere. But it’s a marvel they exist at all.

They first appeared about 480 million years ago, when most of Earth’s land was amassed in the southern supercontinent Gondwana. It would be millions of years before plants or animals evolved to live on land, but the seas were teeming with invertebrates armored in exoskeletons, early jawless fish and the first coral reefs. Roughly 230 million years later, a series of massive volcanic eruptions sent global temperatures soaring.

The resulting extinction event – called the great dying – wiped out about 90% of the world’s species, including 95% of those that lived in the oceans. Among the brittle stars that survived, two species gave rise to more than 2,000 modern species that have evolved since.

Over recent decades, thousands of brittle stars have been collected for research and stored in museums. And lead author of the study, Timothy D. O’Hara of Museums Victoria, has doggedly pursued his mission to unlock the samples’ potential.

“His goal was to assemble all available information on brittle stars by visiting every major collection across the world. That’s a monumental undertaking,” Paulay said. “But the result is the best global dataset available for a group of marine organisms. It is absolutely unprecedented.”

Image from O'Hara et al. (2025)

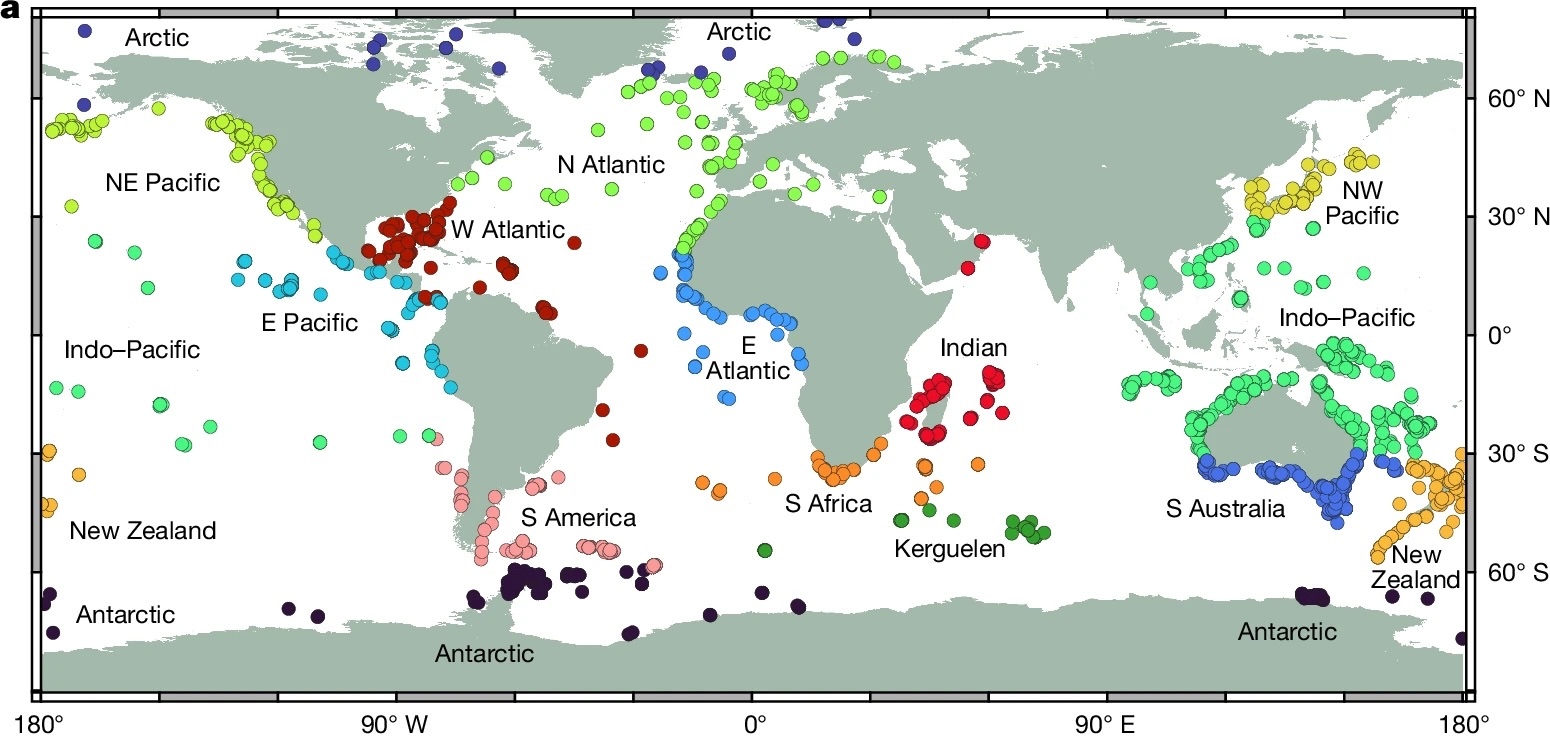

By analyzing these samples, the research team was able to develop a better understanding of how sea life in general migrated and evolved over millions of years. Scientists analyzed 2,699 brittle star samples, collected during 332 research expeditions and preserved in 48 natural history museums worldwide. Compiling survey data allowed them to construct a global map of where brittle stars live, but pairing that with genetic data is what made this study transformative. Genetically testing the samples unlocked a new view of how the animals are related across time and space, and thanks to O’Hara’s lead, the relationships of brittle stars became the best known of any marine group.

Few institutions are better prepared to provide such data than the Florida Museum of Natural History. Paulay and his colleagues have collected thousands of samples – especially in the coastal waters of the Indo-Pacific Ocean – that have been properly preserved for DNA analysis.

“The museum’s collection has risen to top two in the world in terms of how much sequenceable marine material it contains,” Paulay said. “Since I arrived, the collection here has almost tripled in size, all with DNA sequencing in mind.”

Scientists had suspected life in the deep sea to be more connected than in the shallows, and the results of this sweeping study confirmed it. Like many deep-sea animals, the brittle star’s pioneering larvae are the secret to their global reach. After emerging from an egg, the larvae drift with ocean currents, sometimes traveling vast distances before eventually settling on the seafloor and maturing into adults.

In shallows waters, this journey is made more challenging by abrupt shifts in temperature and salinity. Larvae are often confined to their coastal areas because reaching other continents or islands means crossing long stretches of open ocean lacking suitable shallow habitats. As brittle stars become isolated in smaller ranges, they acquire specialized traits to match their local environment, driving diversity. The deep sea, in contrast, may be extreme, but it is continuous and consistent. At 11,500 feet below the surface, impenetrable darkness, crushing pressure and frigid temperatures stretch uninterrupted for thousands of miles.

“The deep sea is very contiguous, and habitat is everywhere. Maybe you can only go 50 miles in one generation, but then you go another 50 miles the next. In the deep sea, you can hopscotch jump across the entire planet. You cannot do that in the shallow water,” Paulay said.

Over millions of years, deep-sea brittle stars in the deep sea have migrated vast distances, leaving a genetic link between populations in the North Atlantic and others on the opposite side of the planet in south Australia. But their distribution is far from uniform. Slow migration is often outpaced by genetic mutation, and extinction looms large in the deep sea, where predators or shifting conditions can wipe out local populations. As a result, today’s brittle stars form a patchwork pattern on the seafloor.

Understanding these patterns and connections required scientists to take a broad view. For Paulay, the novelty of this study lies in its planetary scale.

“It’s essential to zoom out,” Paulay said. “When focusing on something so little, you can lose context in which you operate in. And often the context changes what you perceive to be going on.”

These efforts often spark unexpected collaborations, according to Paulay. He has recently coauthored papers documenting the discovery of over 100 new ribbon worms species off the coast of Oman and over two decades of soft coral surveys in the Indo-Pacific.

“These are long-term collaborations that bring to light major patterns about the ocean. It’s exciting to be part of that,” Paulay said. “But the lack of large-scale biodiversity collecting scares me. What’s represented in collections today is only a fraction of what’s out there, and a lot of it is disappearing. It’s not on the shelves today, and it won’t be there to sample tomorrow.”

Additional authors of the study are Timothy O’Hara, Andrew Hugall, Margaret Haines, Alexandra Weber and Adnan Moussalli of Museums Victoria; Angelina Eichsteller and Pedro Martinez Arbizu of Deutsches Zentrum für Marine Biodiversitätsforschung; Martin Brogger of Instituto de Biología de Organismos Marinos; Marc Eléaume and Sarah Samadi of Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle Paris; Toshihiko Fujita of National Museum of Nature and Science’s Tsukuba Research Center; Jon Kongsrud of University Museum of Bergen, Norway; Sadie Mills of National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research New Zealand; Jennifer Olbers of WILDTRUST; Fran Ramil of Universidade de Vigo; Chester Sands of British Antarctic Survey; Javier Sellanes of Universidad Católica del Norte; and Francisco Solis-Marin of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Source: Gustav Paulay, paulay@flmnh.ufl.edu

Writer: Brooke Bowser, bbowser@floridamuseum.ufl.edu

Media Contact: Jerald Pinson, jpinson@floridamuseum.ufl.edu