To be fair, the newly described Waray dwarf burrowing snake is pretty great at hiding.

In its native habitat on the islands of Samar and Leyte in the Philippines, the snake usually surfaces only after heavy rains, similar to earthworms washing up on suburban sidewalks after a downpour.

So, it may not be surprising that when researchers collected several Waray dwarf burrowing snake specimens, they were unaware they possessed animals unknown to science. The specimens spent years in the herpetology collection of the University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum misidentified as other small, burrowing snakes.

That changed once Jeffrey Weinell, a graduate research assistant at the Biodiversity Institute and lead author of the new species description, took a closer look at the specimens’ genetics. He also sent the snakes to Daniel Paluh, a University of Florida doctoral student, to be CT scanned, a non-destructive way of examining key physical characteristics.

Based on the CT scans and molecular analysis, Weinell and his collaborators determined the specimens belonged to a new genus and species, now known as Levitonius mirus.

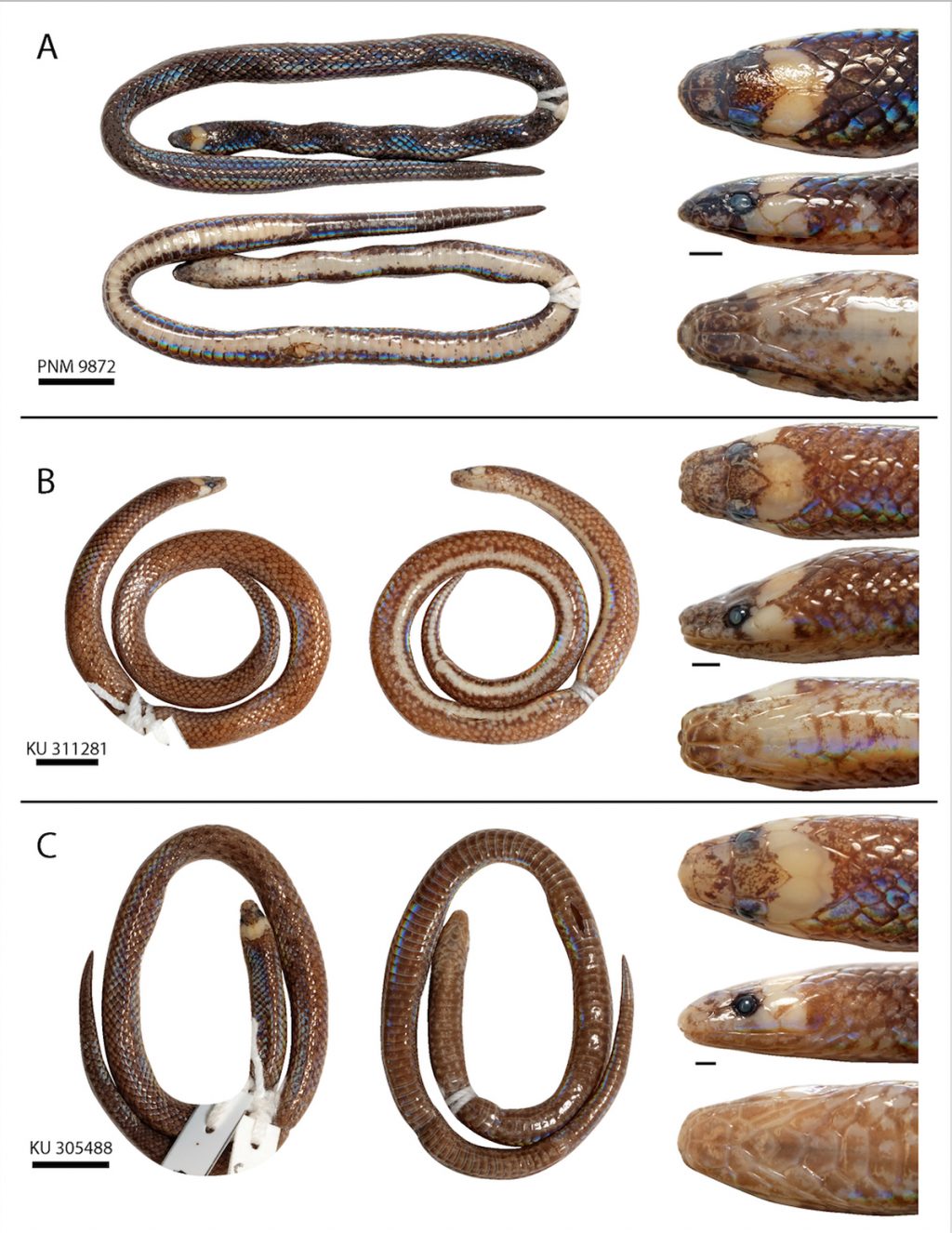

Shorter than a pencil and about as thick, L. mirus is the smallest species in the superfamily Elapoidea, which encompasses hundreds of species, including cobras, mambas, coral snakes and sea snakes. L. mirus is covered in ultra-smooth, iridescent scales that likely reduce friction while it tunnels through soil and leaf litter and is thought to prey on earthworms, Paluh said.

“Because Levitonius mirus is currently only known from three specimens, very little is known about its natural history,” said Paluh, a member of the Blackburn Lab at the Florida Museum of Natural History. “Through CT scanning and studying its skeleton, we were able to make inferences about its ecology, like diet and habitat preference.”

Despite its diminutive size, L. mirus boasts an impressively robust and toothy skull, Paluh said. These teeth, coupled with a narrow, pointed skull, may help the snake capture slender-bodied prey. It also has among the fewest number of vertebrae of any snake species in the world, “likely the result of miniaturization and an adaptation for spending most of its life underground,” Weinell said in a statement.

Pinpointing how the snake should be classified wasn’t a simple task: The Philippine archipelago is an exceptionally biodiverse region that includes at least 112 species of land snakes from 41 genera and 12 families. A close examination of the snake’s DNA and physical features, including its scales, which can differentiate species, led researchers to place it in Cyclocoridae, the only snake family unique to the Philippines.

The new genus was named in honor of Alan Leviton, a researcher at the California Academy of Sciences who has studied snakes in the Philippines since the 1960s, Weinell said. The species name is derived from the Latin word for “unexpected.”

“That’s referencing the unexpected nature of this discovery – getting the DNA sequences back and then wondering what was going on,” Weinell said.

Rafe Brown, professor and curator-in-charge of the KU Biodiversity Institute’s herpetology division, said the description of L. mirus highlights the value of preserving biological collections in research institutions and universities.

“In this case, the trained ‘expert field biologists’ misidentified specimens – and we did so repeatedly, over years – failing to recognize the significance of our finds, which were preserved and assumed to be somewhat unremarkable, nondescript juveniles of common snakes,” Brown said. “This happens a lot in the real world of biodiversity discovery. It’s a good thing we have biodiversity repositories and take our specimen-care oaths seriously.”

According to Marites Bonachita-Sanguila, a biologist at the Biodiversity Informatics and Research Center at Father Saturnino Urios University in the Philippines, the discovery “tells us that there is still so much more to learn about reptile biodiversity of the southern Philippines by focusing intently on species-preferred microhabitats.”

“The pioneering Philippine herpetological work of Walter Brown and Angel Alcala from the 1960s to the 1990s taught biologists the important lesson of focusing on species’ very specific microhabitat preferences,” Bonachita-Sanguila said. “In the case of this discovery, the information that biologists lacked was that we should dig for them when we survey forests. All this time, we were literally walking on top of them as we surveyed the forests of Samar and Leyte. Next time, bring a shovel.”

She added that habitat loss as a result of human-driven land use, such as the clearing of forests for agriculture, is a prevailing issue in the Philippines today.

“We need effective land-use management strategies, not only for the conservation of celebrated Philippine species like eagles and tarsiers, but for lesser-known, inconspicuous species and their very specific habitats – in this case, forest-floor soil, because it’s the only home they have.”

The study was published in Copeia.

Cameron Siler of the University of Oklahoma is also a study co-author.

Models of the fossils are available on MorphoSource, an open-access repository of 3D data.

The work was funded by the National Science Foundation. CT scans were generated from the NSF-funded oVert project.

Sources: Jeffrey Weinell, jweine2@gmail.com;

Daniel Paluh, dpaluh@ufl.edu;

Rafe Brown, rafe@ku.edu;

Marites Bonachita-Sanguila, mbsanguila@urios.edu.ph