“I did hear about your hopefully temporary transfer into higher administrative realms. My only advice is to ditch it as soon as possible.” Noted evolutionary biologist and author Stephen Jay Gould typed up the preceding exhortation in a letter he wrote to Doug Jones in 1996, referencing his recent appointment as interim director of the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Today, Monday, June 30, is officially Jones’ last as full-time director of the museum, meaning he decided not to take Gould’s advice. But he did seriously consider it.

Jones had been asked to fill the role by the University of Florida’s provost, and he agreed hesitantly. Jones had no real administrative aspirations to speak of. He was a research paleontologist on the rising incline of his career. He’d recently accepted a full-time faculty appointment with the Florida Museum, in which he busily taught, conducted research, published results and mentored graduate students. Being a director would almost certainly put a stop to all of that.

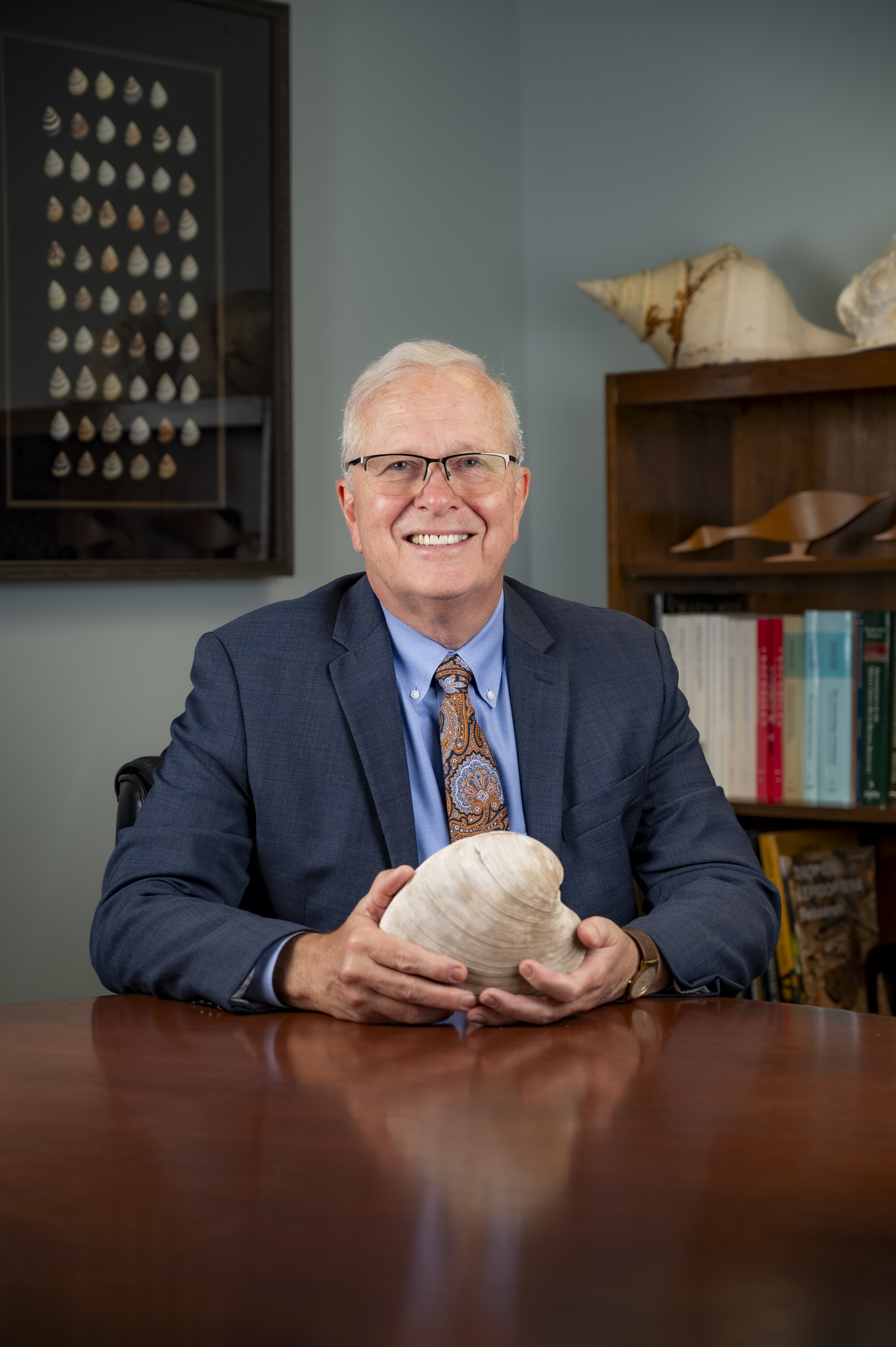

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

He knew this from experience. He’d spent the previous two years as chair of the museum’s natural history department, which came with its fair share of strategic governance and bureaucratic paper trails. But he hadn’t exactly asked for that position, either.

“Our son was being born at North Florida Hospital, and I got a call,” Jones recalled. “I thought they were just saying congratulations.”

They weren’t. The previous chair had stepped down unexpectedly, prompting faculty members to hold an emergency meeting to pick a successor. Because Jones was indisposed and could not attend, he got the short straw. The faculty had unanimously selected him as the next chair, and despite his protestations, their decision remained firm. So Jones reluctantly accepted.

But interim positions are, by definition, temporary, so he didn’t worry much about the time spent away from his fossil mollusk research, which had been going exceedingly well up to that point. Jones was particularly interested in the way natural cycles, like the Earth’s annual procession around the sun, can become physically imprinted in plants and animals. Just as trees produce alternating light and dark rings of wood over the course of a year, mollusks add distinct layers to their shells, which can be used to determine their age. It was this work, incidentally, that put him in touch with Gould, who’d been stumped by a paleontological mystery that Jones was uniquely positioned to solve. It had to do with something called the devil’s toenails, and it went like this:

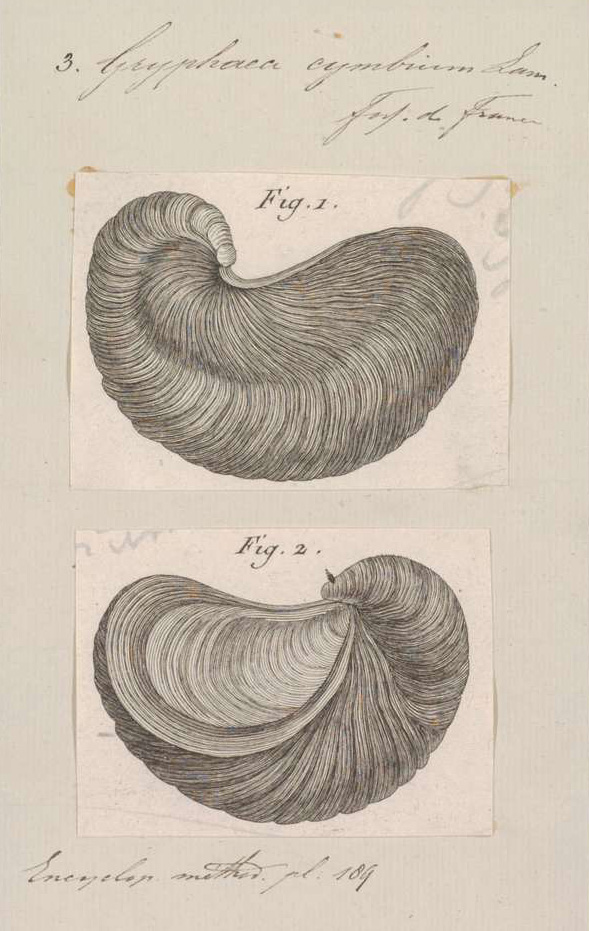

Millions of years ago, there was a type of oyster in the genus Gryphaea, colloquially known as the devil’s toenails, that inhabited shallow marine environments. It got its name from the coiled and gnarled shape of its lower shell, which does in fact resemble an infernal toenail. Their fossils are abundant in parts of the United Kingdom, and they can be found in multiple different stratigraphic layers, from the Jurassic up past the extinction of the dinosaurs.

This has resulted in a lot of excitement and contention in the paleontology world, because Gryphaea evolved in a way that’s left much open to speculative interpretation. Gould referred to it as — with perhaps a hint of hyperbole — “a defining paleontological event of our own century.”

Like modern oysters, Gryphaea had two interlocking shells that could be opened or closed as needed. In the early 20th century, the British geologist Arthur Trueman noticed that the top shells of the more ancient Gryphaea seemed to be relatively flat, with the general shape of a big toenail or dinner plate. Over time, however, the lower shell became increasingly coiled, taking on the appearance of a claw or talon.

Trueman suggested that the lower half of Gryphaea shells eventually became so coiled that they pressed up against the upper shells, which would have prevented them from opening. This would have resulted in starvation, since oysters must open their shells to filter water for food. Thus, Trueman reasoned, Gryphaea likely coiled itself into extinction.

This theory was proven fabulously incorrect within a few decades, but the gradual coiling over time was a real phenomenon, and it gave scientists the rare opportunity to retroactively observe evolution in action. It also meant they could really get down into the nuts and bolts of evolutionary mechanics and test different ideas, such as Gould’s favored theory of punctuated equilibrium versus that of gradualism.

There was just one problem. Gryphaea changed the shape of their shells by either speeding up or slowing down their growth, and there was no way to tell which of these had been the case.

Enter Doug Jones.

He’d spent most of his career up to that point developing sophisticated techniques to reconstruct the life history of fossil clams using nothing more than their growth rings. By analyzing isotopic differences in and between growth rings, he could determine what stage of development the clam had been in when it died, how fast it grew, and the time of year it spawned and/or died.

In 1992, Jones had spent part of his sabbatical collecting fossils throughout the United Kingdom and came back with a grab bag of invertebrate goodies that included about 2,000 Gryphaea specimens. He was aware of the Gryphaea problem, which Gould had written about at length in multiple papers.

University of Amsterdam

“I thought I had a good solution, so I wrote to him during the holidays,” Jones said. Gould wrote back, saying it was the best Christmas card he’d ever received, and they should work on the problem together.

A star-struck Jones, who’d idolized Gould throughout college and his early career, got to work. He sawed through the Gryphaea specimens to expose their growth rings. Then he used a drill with an incredibly fine bit to extract fossilized shell for study. He crunched the numbers with analytical finesse and quickly came up with an answer for Gould.

“I started slicing and dicing all the way up the sequence, and I could show that individuals began to grow faster and bigger, but they didn’t live as long.”

This revelation answered another perplexing question regarding Gryphaea as well. Not only did they change the shape of their shells; the adults also seemed to disappear over time, with fewer mature Gryphaea closer to the present. This wasn’t because they lived shorter lives, given that even organisms with incredibly short lifespans complete a growth cycle from juvenile to maturity. The new results suggested that Gryphaea had sped up their growth rate, but not their rate of development, meaning the adults tended to look like juveniles.

Jones and Gould published their results in 1996. For Jones, looking back, it was the culmination of a fruitful career and a good note to end things on. Because the more work he did as interim director, the more he realized he had a flair for it. He found himself thinking less about fossils and more about the strategies employed by natural history museums to get people excited about life on Earth.

“I found it personally fulfilling, and I knew I could make a difference.”

Still, he decided not to throw his hat in the ring for the permanent position. That also required some prodding. The provost who’d given him the interim appointment had since taken a job at another institution, but his successor had similar predilections regarding Jones’ ability to do the job well. She called him up to say she didn’t see his application in the mix and would be disappointed if it didn’t materialize before the closing date.

He was officially offered the permanent position in 1997, and he’s been at the helm of the Florida Museum ever since. He currently holds the title for longest-serving director of a major natural history museum in the U.S. He received the distinguished service award from the American Alliance of Museums in 2024 and the lifetime achievement award from the Florida Association of Museums in 2017.

Jones has shepherded the museum through times both plentiful and paltry. He played a major role in garnering funds for a new and modern exhibit hall in 1998, which gave visitors a more immersive and visceral experience while freeing up a significant amount of space for the museum’s increasingly massive collection of specimens. He maintained a steady hand through the economic downturn of 2008 and the sudden halt in visitation during the COVID19 pandemic. He obtained $13 million in 2003 to establish the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity, which now houses one of the world’s largest moth and butterfly collections. He secured funds for the construction of a special collections building in 2022, which now houses all the museum’s alcohol-preserved specimens. And, in parting, he helped launch the museum’s ongoing expansion project earlier this year, which will add several educational facilities to the exhibit hall.

This is in addition to the more than 100 scientific papers and abstracts he published as a researcher, a litany of professional awards and affiliations, and dozens of grants and contracts.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

If there is any common goal among directors as a profession, it’s to direct the institutions under their charge safely throughout their tenure and, if possible, leave them in a better state than the one they found them in. If such is the measure of success, then Jones has undeniably succeeded.

He’s still a little flummoxed as to why he traded in a promising research career at the height of his power and productivity for one embedded in the grinding machinery of academic administration. But for all that the position was foisted upon him, the decision he made in 1997 to stay on as full-time director was not out of keeping with his interests and overall demeanor.

While he was an undergraduate student at Rutgers University, Jones was a member of a natural history appreciation club and would occasionally give museum tours to children. Watching their unfiltered fascination and wonder — things which, though he still felt them, had been tempered with age — stirred something in him.

“I still don’t understand it all, but I knew that museums had the power to influence people’s imagination, especially people that came in with curiosity,” he said. “For me, curiosity is a big thing, and museums are agents of curiosity.”

The world has changed significantly in the nearly three decades since Jones swallowed his qualms and signed on as director, but the museum’s mission to connect people with the natural world through inspirational education, outreach and research has remained steadfast, due in part to his leadership. Its exhibits and educational programs unambiguously advocate for environmental protection, knowledge of and respect for Indigenous culture, and humility when faced with the magnitude of natural phenomena.

“We have a responsibility as humans to care about our environment, and we owe it to people to tell them what’s happening to it.”

Jones didn’t accomplish all this alone. The museum is full of dedicated educators, researchers and administrators who work tirelessly in service of a better world. They’ve made incalculable contributions and, for Jones, made the job of director reciprocally meaningful and worthwhile. “I was encouraged by the dedication and enthusiasm of my colleagues up and down the halls.”

His tenure at the museum hasn’t gone uncontested, however. While working as interim director, Jones, his wife and their 3-year-old son went to visit his parents. There, they shared the good news that they had another child on the way, prompting his mother to take him aside and admonish him. As he recalls, she said: “Doug, you’ve indulged yourself all this time, but you’ve got a family now that’s growing. You need to think less about yourself and what you want to do and more about how you’re going to support your family and kick this museum nonsense to the curb.”

Jones, bemused by his mother’s loving but somewhat misguided advice, found a way to simultaneously flourish in the field of natural history and raise a beautiful family. The museum is better off for his having done so.

Jones will continue at the museum as curator of the invertebrate paleontology collection starting July 1.

As a gesture honoring Doug and his tenure as director, the Douglas S. Jones Endowment has been created with inaugural gifts from Florida Museum supporters and longtime friends, Mike Toomey and Jim and Lori Toomey.

If you’d like to make a donation, you can do so by visiting the endowment page.

Source: Douglas S. Jones, dsjones@flmnh.ufl.edu

Media contact: Jerald Pinson, jpinson@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-294-0452