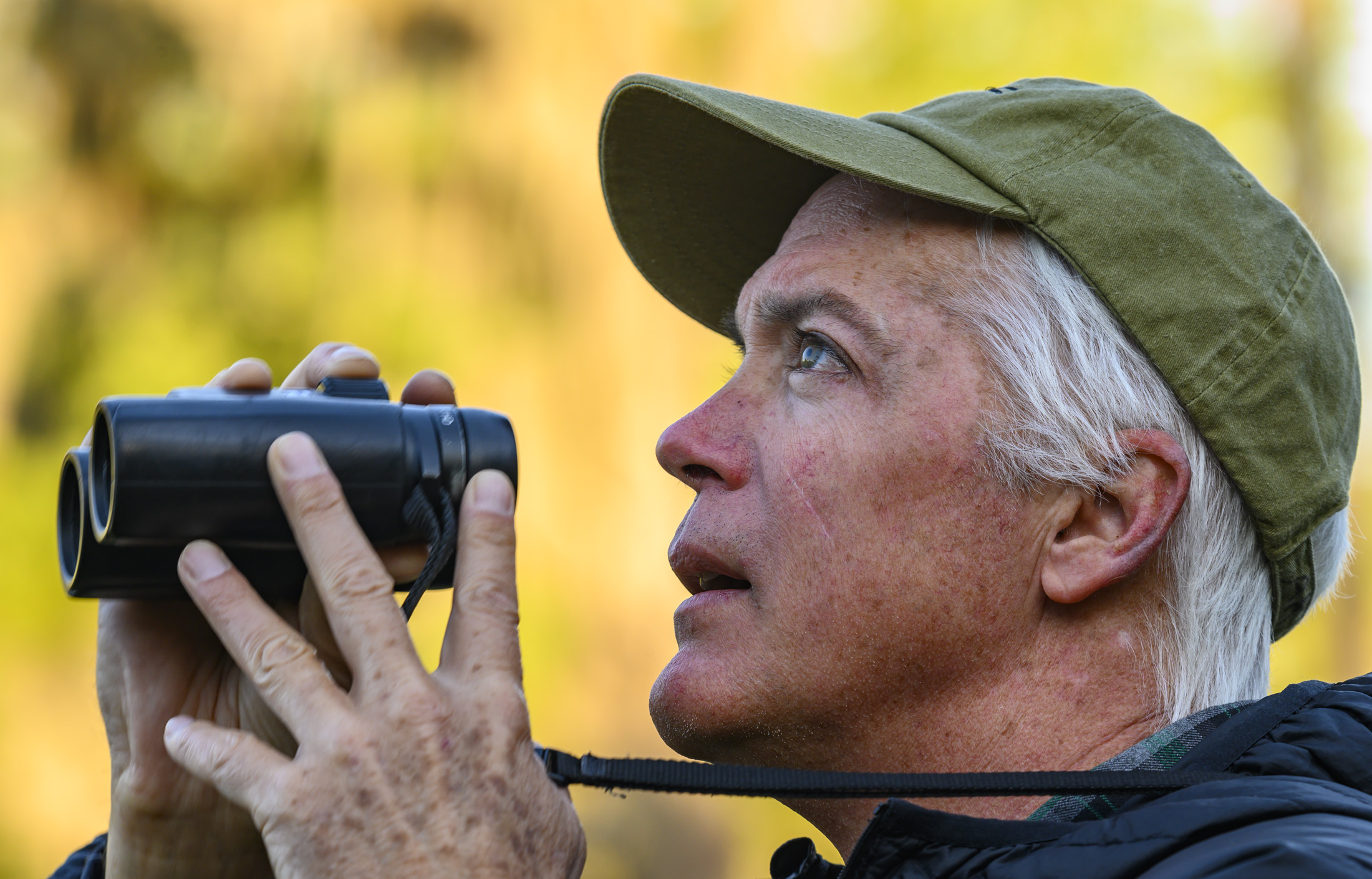

An hour after sunrise, Andrew Kratter stands in the dew-soaked grass of an East Gainesville graveyard, watching the sky for what looks like a bowling pin with wings – the common loon, Gavia immer.

Kratter, manager of the Florida Museum of Natural History’s ornithology collection, has scouted for loons every morning from mid-March to mid-April for nearly two decades. It requires a sharp eye: The seabirds streak overhead at about 60 miles an hour on their spring migration from the Gulf of Mexico to the Atlantic Ocean.

“Most of the time I’m seeing them up to a mile away, and I only have a couple seconds to identify them,” he says. “But they’re so distinctive, and there’s only one species of loon flying, so it works out pretty well.”

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

Gainesville is the midpoint of a little-known loon flight corridor discovered by Kratter, thanks to a tip from local birder Rex Rowan. Each spring, loons that overwinter in the Gulf leave Cedar Key at dawn and fly northeast over the state to Jacksonville Beach, a trip that takes a couple of hours. From there, they likely join northbound loons that trace the Atlantic coastline as they head to breeding grounds in eastern Canada, Kratter says.

“There’s one.” He points to a speck in the pale sky.

Even at this distance, one can make out the loon’s distinctive breeding plumage – a jet-black cap and striped collar set off by a long white belly. Jutting beyond its tail is a pair of large feet, propellers for diving and maneuvering underwater. A 4-foot wingspan powers the loon’s swift, shallow flight.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

As Kratter raises his binoculars, birders at eight other stations across the county follow suit. In seasons past, he largely counted loons alone, his faithful dogs by his side – first, Ani the black Lab and now collie-husky mix Newman. Other watchers occasionally emailed tallies of loons they’d seen from backyards or parks.

But this year, a grant from the Duke Energy Foundation’s Powerful Communities: Nature initiative enabled Kratter to recruit and train a team of citizen scientists, including University of Florida students, to carry out an organized census of Florida’s migratory loons. A second group, led by longtime loon researcher Paul Spitzer, records loons flying over St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, south of Tallahassee, on another flyway that leads to Minnesota, Michigan and central Canada.

Conserving a North American icon

Tracking the migration can provide insights into potential threats to loon populations, Kratter says. Loons were the third most common bird species to wash ashore in the wake of the BP oil spill in April 2010, which likely caught younger loons that had not yet migrated or would have spent the summer in the Gulf.

“Something like that can have devastating effects,” Kratter says. “Tens of thousands of loons spend the winter on the Gulf of Mexico.”

An additional hazard is rising sea temperatures, which could reduce fish stocks, making the Gulf less habitable for wintering loons.

Photo courtesy of John Picken, CC BY-SA 2.0

Previously, scientists focused mainly on threats to loons at their breeding grounds. The 2016 State of North America’s Birds report listed common loons as a species of moderate conservation concern. They need clean, unpolluted waters and little to no human disturbance to breed, making them an indicator species – a living barometer of an area’s environmental health.

Over-development of shorelines, which are crucial nesting sites, led to plummeting loon numbers in the 1970s, and while populations have generally rebounded, some scientists think the species may never return to its historic levels. Loons also face threats from acid rain and mercury pollution, lead poisoning from ingesting fishing sinker weights and biotoxins such as botulism, introduced to the Great Lakes by invasive zebra and quagga mussels.

Research such as Kratter’s can add to what scientists know about the birds’ behavior, with the goal of preventing G. immer from becoming the next monarch butterfly: a once-common North American species now imperiled by habitat loss and human activities.

“Conservation of migrant birds requires analyzing threats across an entire year of comings and goings,” Kratter says. “The discovery of a previously unknown migration route used by thousands of common loons, but constrained in time and space, creates an opportunity to better monitor this iconic species.”

Loons find a Florida shortcut

Kratter didn’t become a loon specialist until Rowan alerted him to the local passers-by in 2000.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

“I was like, ‘What? Loons in Gainesville?’” Kratter says. “I went out a few mornings after his email, and sure enough, I saw some loons flying. We didn’t even know they migrated across Florida.”

The reason for his surprise was that loons limit their flight over land. They need wide expanses of open water for resting, feeding and taxiing into flight. Their big, back-set feet make them ungainly walkers, and loons that touch down on dry land risk getting grounded. Better-studied loon migratory pathways take them along coastlines or over chains of lakes where they can stop to forage. Why would they cross Florida?

When Kratter studied the state’s geography, however, it suddenly made sense. The loons’ pathway takes them over North Florida’s narrowest point, where the Gulf Coast pinches in between the bulges of Big Bend to the north and Tampa Bay to the south. The flyway is no accident: It’s a strategic navigational choice over one the shortest possible overland routes, a distance of about 122 miles.

“They’re taking advantage of this smaller width of the peninsula and crossing to the Atlantic,” Kratter says. “From the Atlantic, they can go all the way north to Canada, if they want, and not have to fly over land.”

Still, Kratter sometimes witnesses a loon that has changed its mind mid-route and is beating its way back west.

“They’re making flight decisions about whether they feel good about doing this overland flight, which is a very stressful time,” he says. “But Gainesville is pretty much halfway, so it’s like swimming halfway across a river and saying, ‘I’m not going to make it. I better go back.’”

With additional birders posted around the county, Kratter has started picking up on more nuanced flight patterns that were impossible to spot alone.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

“It’s not just a random 20-mile-wide expressway with loons patchily distributed across it,” he says. “There are streams and actually big differences between different stations depending on the day. We can start to put these variations in the context of what’s happening with the weather and how the loons are responding.”

The extra eyes have also enabled Kratter to get a more accurate sense of loon numbers, he says. On March 31, the birders tallied 325 loons, a new single-day record, and by the end of the migration, they had counted 2,190, smashing the previous seasonal best of 895. Kratter says the spike doesn’t necessarily mean loon populations are booming. Still, there are more loons than he thought there were.

“The high number of loons indicates that this migratory pathway is even more important than I had imagined.”

Source: Andrew Kratter, kratter@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-1973