A ruler and scale can tell archaeologists the size and weight of a fragment of pottery – but identifying its precise color can depend on individual perception. So, when a handheld color-matching gadget came on the market, scientists hoped it offered a consistent way of determining color, free of human bias.

But a new study by archaeologists at the Florida Museum of Natural History found that the tool, known as the X-Rite Capsure, often misread colors readily distinguished by the human eye.

Photo by Bloch et al. in Advances in Archaeological Practice

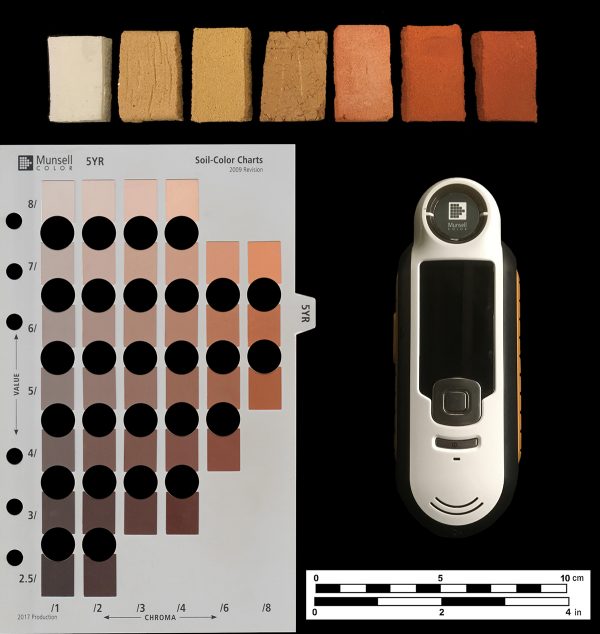

When tested against a book of color chips, the machine failed to produce correct color scores in 37.5% of cases, even though its software system included the same set of chips. In an analysis of fired clay bricks, the Capsure matched archaeologists’ color scores only 35% of the time, dropping to about 5% matching scores when reading sediment colors in the field. Researchers also found the machine was prone to reading color chips as more yellow than they were and sediment and clay as too red.

“I think that we were surprised by how much we disagreed with the instrument. We had the expectation that it would kind of act as the moderator and resolve conflicts,” said Lindsay Bloch, collection manager of the Florida Museum’s Ceramic Technology Lab and lead study author. “Instead, the device would often have an entirely different answer that we all agreed was wrong.”

Identifying subtle differences in color can help archaeologists compare the composition of soil and the origins of artifacts, such as pottery and beads, to understand how people lived and interacted in the past. Color can also reveal whether materials have been exposed to fire, indicating how communities used surrounding natural resources.

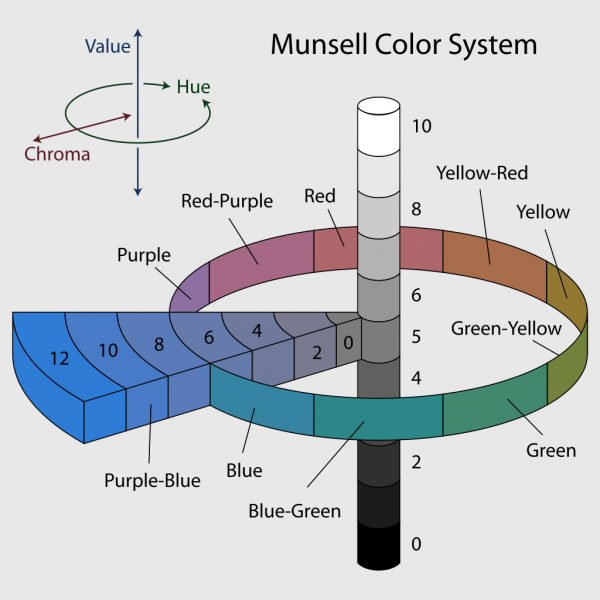

Today, the Munsell color system, created by Albert Munsell in 1905 and later adopted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for soil research, is the archaeological standard for identifying colors. Researchers use a binder of 436 unique color chips to determine a Munsell color score for artifacts, sediment and objects such as bones, shell and rocks. These scores enable archaeologists around the world to compare colors across sites and time periods. But the process of assigning scores can vary based on lighting conditions, the quality of a sample and the perspective of the researcher.

This study is the first to test and record the accuracy of the X-Rite Capsure, a device made by the same company that owns the color authority Pantone. Although marketed to archaeologists, the device was originally designed for interior designers and cosmetologists, not research, Bloch said.

“I think the main takeaway was just sort of surprise that it’s something that is marketed for our field, specifically for archaeologists, but hasn’t been made for us and the kind of data we need to collect,” she added. “When you read the manual, it says you should always verify that the color the machine tells you looks right with your eyes, which seems to negate the use of the instrument.”

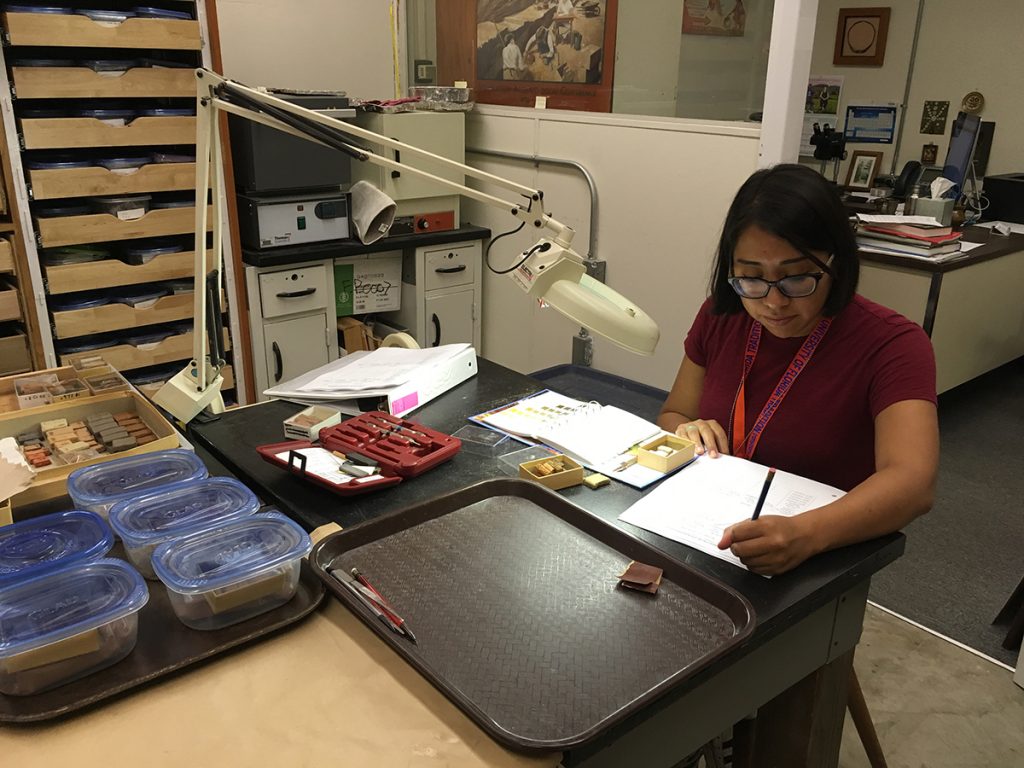

In an experiment designed with the help of University of Florida undergraduate researchers Claudette Lopez and Emily Kracht, the team tested the Capsure’s readings of the three elements of Munsell’s system: a color’s general family, or hue; intensity, also known as chroma; and lightness, also called value.

The team first tested the Capsure on all 436 Munsell soil color chips, rating its reading as correct if it matched the exact score on a chip three out of five times. It correctly scored 274 chips. Of its errant readings, about 75% were misidentifications of hue. The Capsure was consistent, though often wrong, producing the same reading five times for 89% of the chips.

To determine how well the machine performed in a typical laboratory setting, the team tested its color readings of 140 pottery briquettes that had been assigned Munsell scores by Lopez. The Capsure matched the archaeologist’s scores in 35% of cases, again tending to misread hue. It proved consistent in this second test as well, yielding the same score across all trials of more than 70% of the briquettes.

In the most challenging of color-identification conditions – outdoors, where lighting and texture can vary – the machine only matched archaeologists’ scores of sediment samples about 5% of the time, often rating a shade darker or lighter. For one sample, the Capsure reported colors from five different families, even though archaeologists agreed the sediment was a single hue. Bloch said the discrepancy was likely due to moisture, sand and shells, which don’t usually interfere with human observations.

Image courtesy of Lindsay Bloch

Unlike some other methods of identifying color, the Capsure is a remote control-sized device that can provide a reading in seconds. Bloch said the tool’s simple design and accessibility lend it to other scientific applications, but that the team’s results point to a need for further scrutiny of how archaeologists record color.

“This new tool has really forced us to see that color is subjective and that, even with a supposedly objective instrument, it may be much more complicated than we’ve been led to believe,” she said. “We need to pay really close attention and record how we’re describing color in order to make good data. Ultimately, if we’re putting bad color data in, we’re going to get bad data out.”

Bloch said she would give the Capsure three out of five stars for being easy to use and offering helpful ways to store data.

“The ding is for the quality of data because it’s still kind of unknown. At this point, I think that our team would say the subjective eye is better.”

Co-authors of the study are Lopez and Kracht, Jacob Hosen of Purdue University and the Florida Museum’s Michelle LeFebvre, Rachel Woodcock and William Keegan.

Funding for the research came from the University of Florida Caribbean Archaeology Fund.

The researchers published their findings in Advances in Archaeological Practice.

Source: Lindsay Bloch, lbloch@floridamuseum.ufl.edu